By Sebastien Hayez. Published July 15, 2023

Fonts for Screens

Previous articles are here:

- Fonts for Books

- Fonts for Posters

- Fonts for Signage (coming soon)

Digital technology is a constantly evolving field. The technical standards in place have a limited lifespan in the face of innovation, whether in terms of programming languages, web browsers, multimedia design software or the evolution of reading terminals (desktop, laptop, smartphone, tablet, connected devices, etc.).

So, if you have to learn the technique on your own, prefer manuals or websites that are less than 2-3 years old, if not even less than a year old. Also, beware of trainers who are no longer up to date and who throw out rather vague or generalist aphorisms.

For example, until the advent of smartphones, screens had a lower definition than printed documents: 72 ppi compared with 300 dpi for paper. Today, these figures are no longer valid, and a recent smartphone has a screen with an average definition of 1080 x 2400 pixels: the ratio in inches therefore corresponds to over 300 ppi.

Other obsolete data: typography must be that of the operating system or of generally defined substitutes, serif, sans and so on. This was true before fonts were embedded on computer servers, and even before Google Fonts. Since 2009, fonts have also been available in Web Open Font Format (WOFF), a format similar to Open Type, enabling fonts to be deposited online and displayed on any reading terminal.

With these two corrections, design for the screen is not so far removed from classic reading on paper. Before going any further into the subject, it's a good idea to catch up by reading the previously published articles on publishing and poster typography.

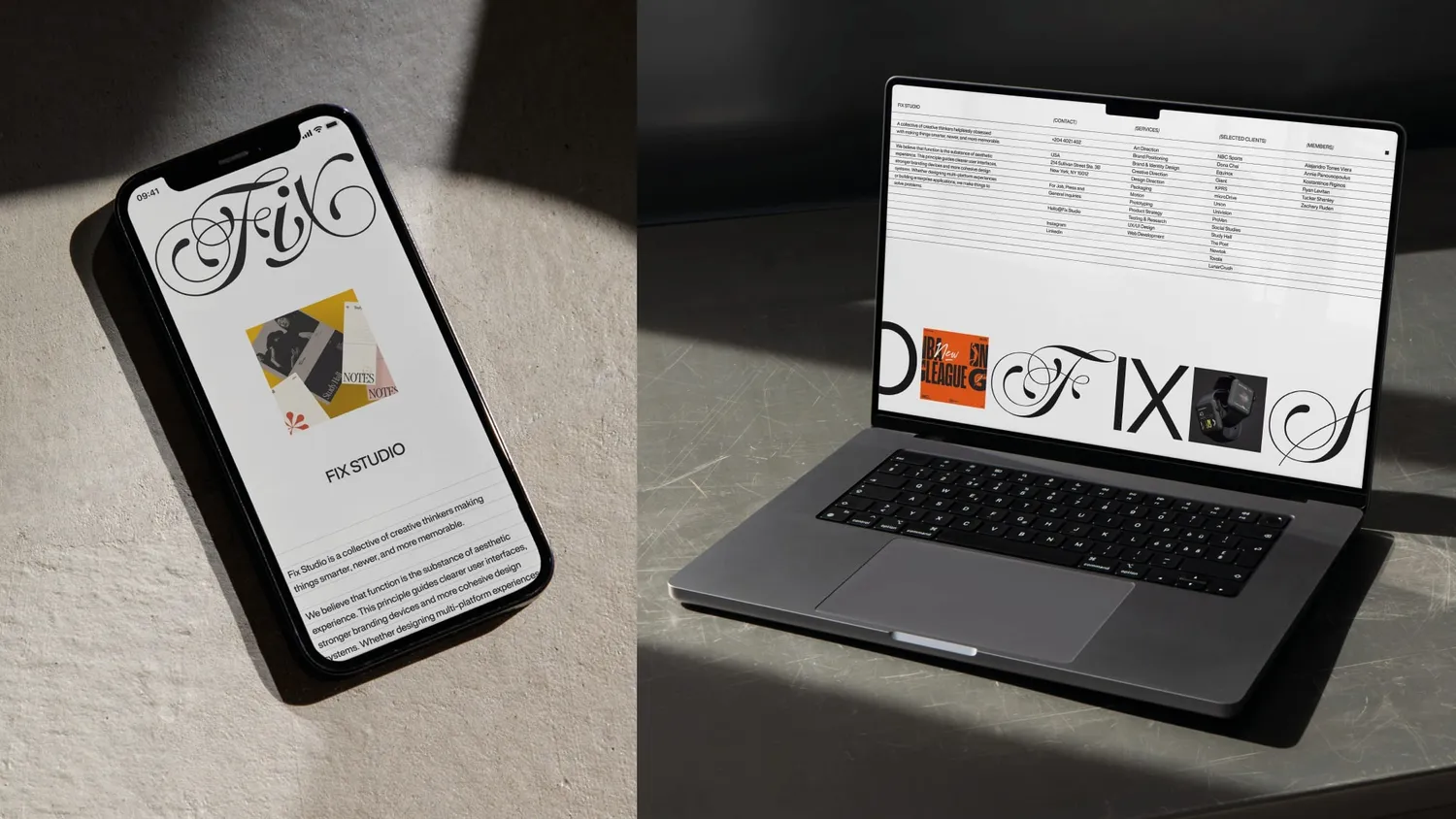

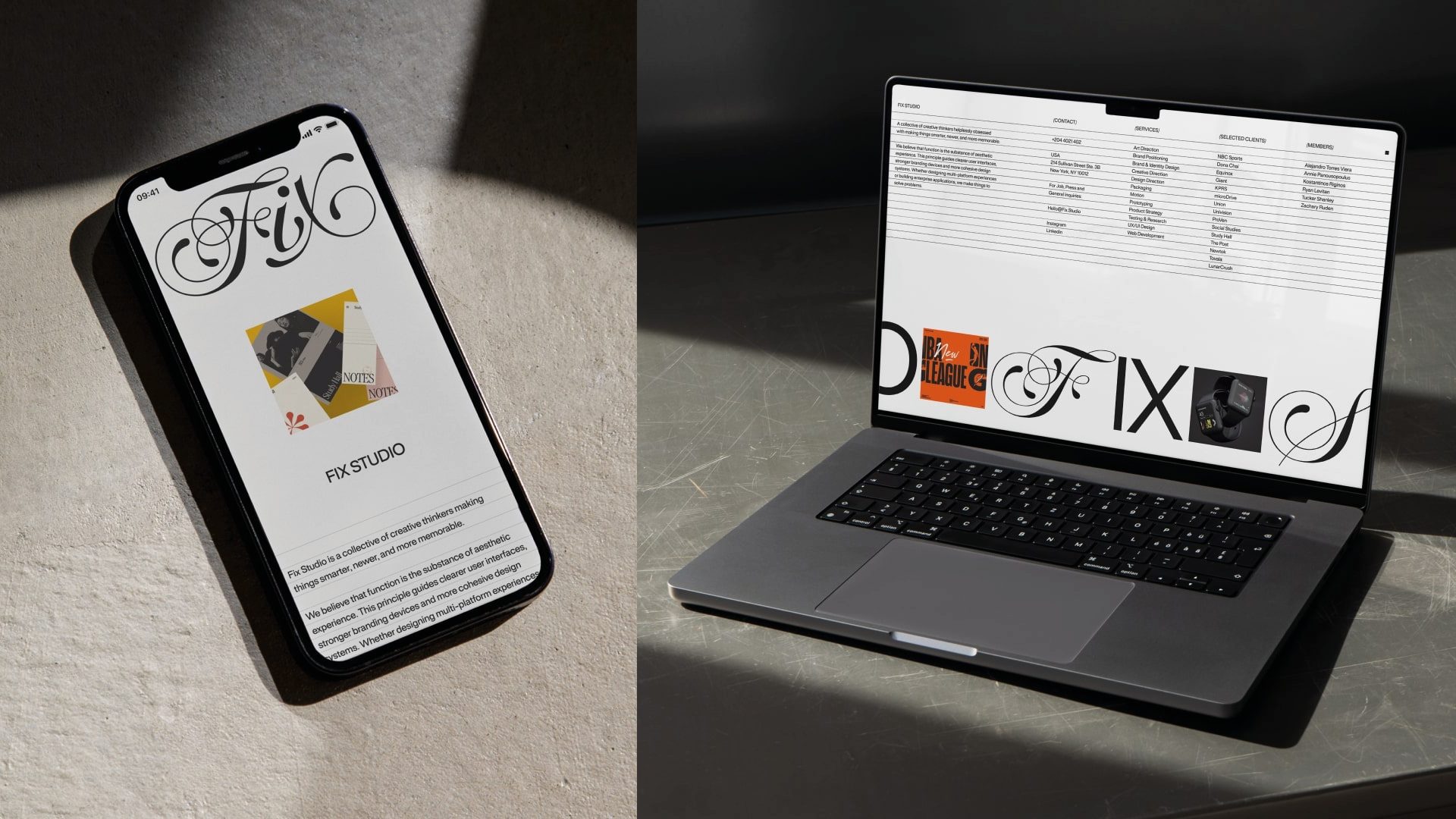

Sometimes, a website can be designed as simple and impactful as a huge poster.

Defining your typographic palette

Before going into the details of typographic choice, it's important to distinguish between different types of on-screen display. Composing the credits for a film or TV series is a different typographic exercise from designing a commercial website displayed on a smartphone. The former is quite similar to the design of a poster or book cover, while the latter is far more technical and problematic. For the purposes of this article, we'll focus on the case of web publishing.

As we've already seen in previous articles devoted to publishing and posters, choosing typefaces is a matter of sensitivity and cultural and economic context - in short, a matter of being in tune with the psychology of your audience. Graphic design means respecting the target audience and fulfilling the objectives defined by the client. Breaking this triune balance between client, audience and designer means project failure.

1. Define the target audience with your client: he will tend to say that he's targeting everyone, in which case you can reply that he won't reach anyone. Achieving a realistic objective is more profitable than reaching people randomly and without personality.

2. Once you've completed the first step, you'll have a clearer idea of how to match your understanding of the audience with the connotations of the typography. A website for a toy shop will be typed differently if the audience is an adult audience composed of geeks, teenage gamers or young parents who've had their first child.

3. Compose your font pairing (see here, but also there & there) respecting the rule of no more than 3 typefaces, unless your purpose and aesthetic bias allow it. This font-pairing is also based on taking hierarchies into account: title levels, running text, captions, etc.

Managing the display system

The real challenge for the web designer is to know how to finely manage displays on totally different terminals and in totally different viewing contexts.

Today, a web page can be displayed on a large TV screen, on a large desktop screen for work, a laptop has a smaller display, but much less than that of a tablet or smartphone.

Desktop first

The design of a website relies on a balance between functionality and design. Rather than starting with a design adapted to medium-sized terminals, such as the tablet, start with what offers the most freedom, namely the computer screen. It's the design that will guide your creation: once the graphic identity has been established, you can then fine-tune your creation so that the site's functionalities and general ergonomics are consistent.

This use show how the simplicity leads to an elegant and balanced design.

The typographic choice can then make use of typefaces adapted to large titling, ligatures or other Opentype features.

The typographic palette can be more extensive than on other terminals: in fact, the computer screen offers a surface and a quieter reading experience conducive to dazzling the viewer's eye. In short, it's the cinema screen for detailed viewing and maximum sensations.

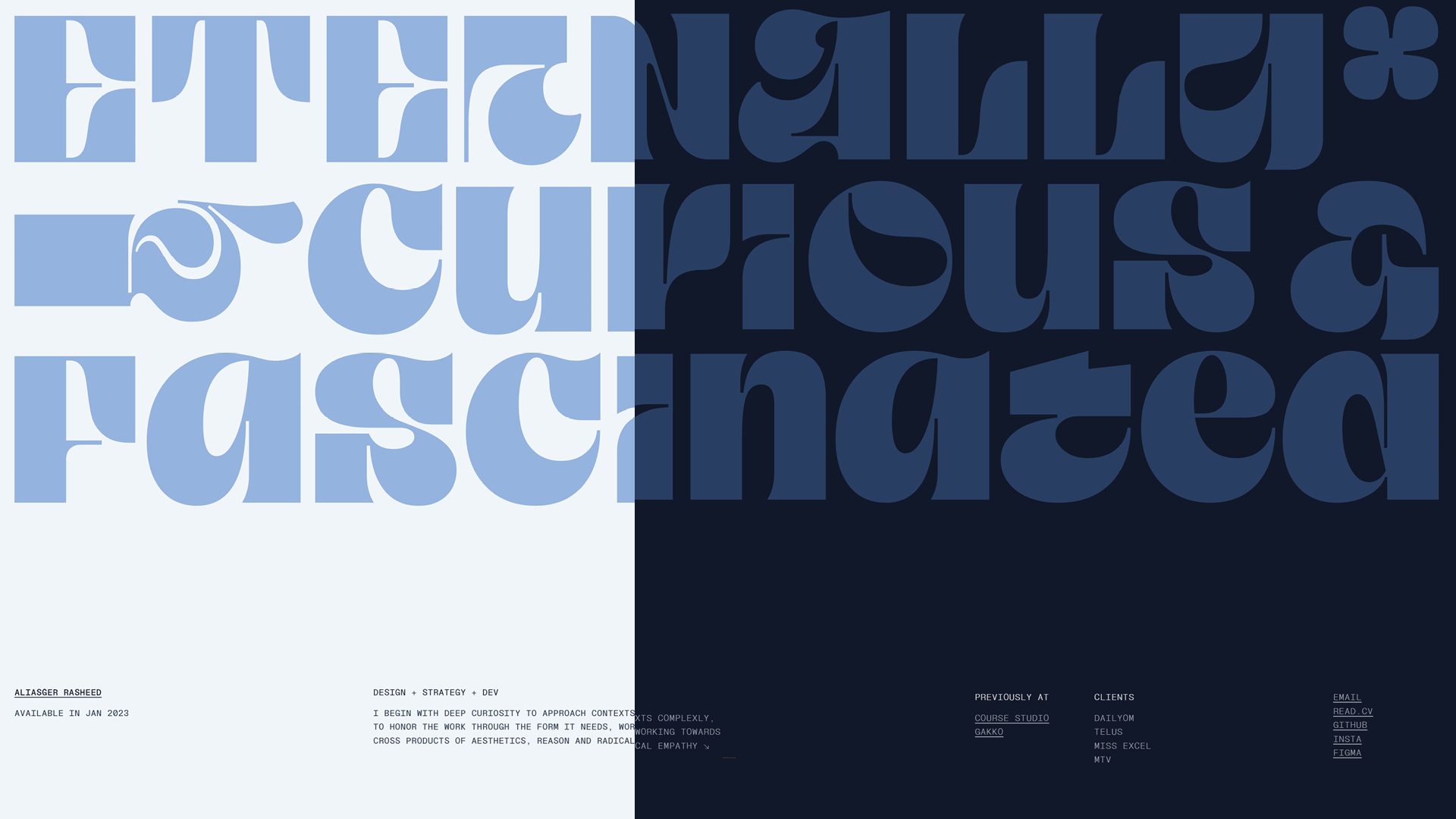

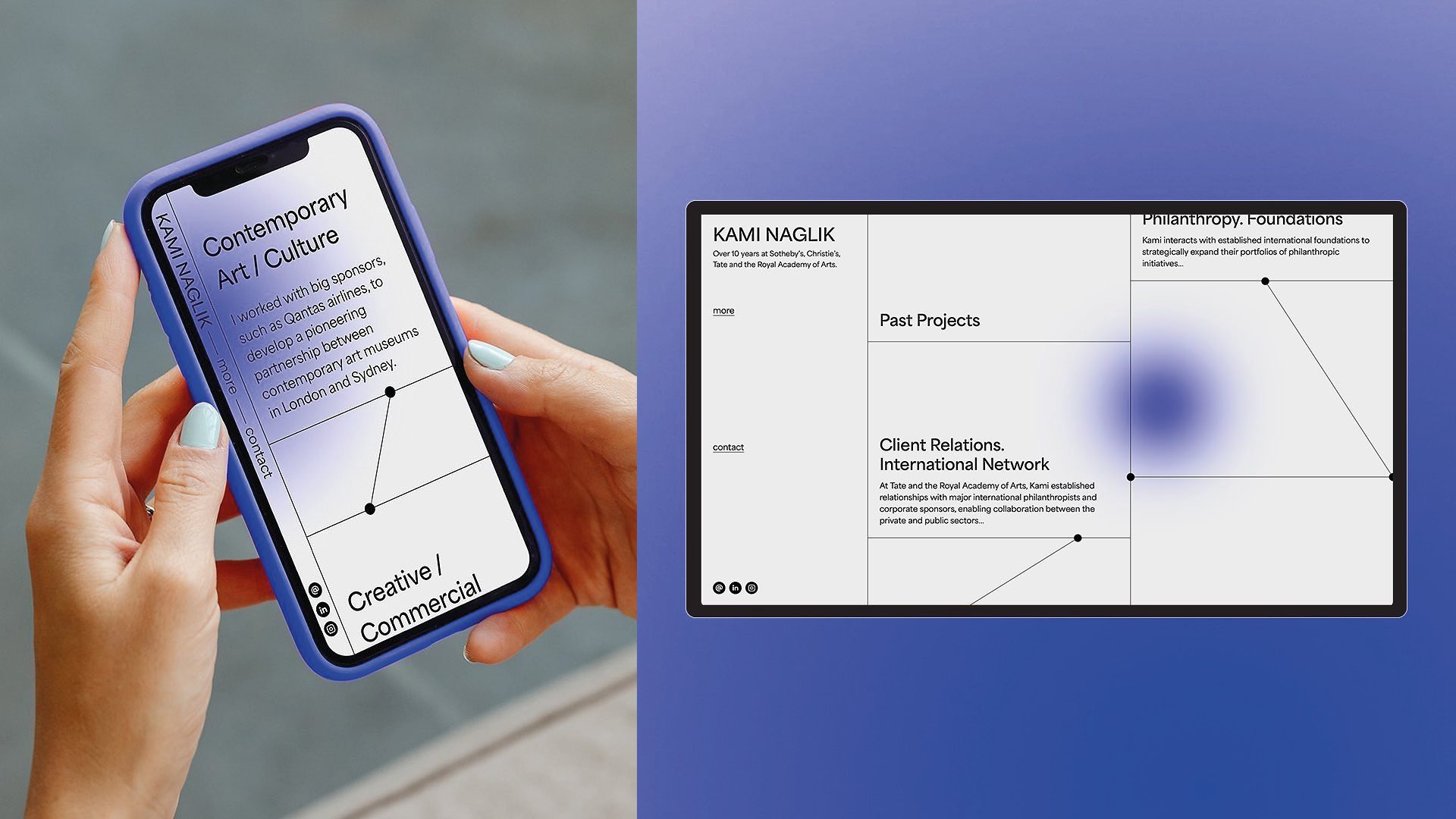

Laptop & tablet for a balance

The formats of these two terminals are a good compromise between freedom of space and optimized ergonomics. Paradoxically, this format corresponds in spirit to the early days of the web, when desktop screens were relatively small and functionalities limited.

The aim of this adaptation is to reduce display functionalities to offer more efficient reading without losing too much in the way of design. Colors and graphics will be similar, but typographic choices may be narrowed down to more legible typefaces for small formats and variable lighting conditions.

It's important, however, to maintain a high degree of consistency between your desktop typographic palette and these formats: title typography will be reduced in size, possibly without its ligatures or options, while commercial typefaces may be fatter. A few substitutions may be made if you have many typographic families on the same screen.

This Swiss like design, grid, typography and color, is the perfect design for various browsers, on smartphone or wide screen.

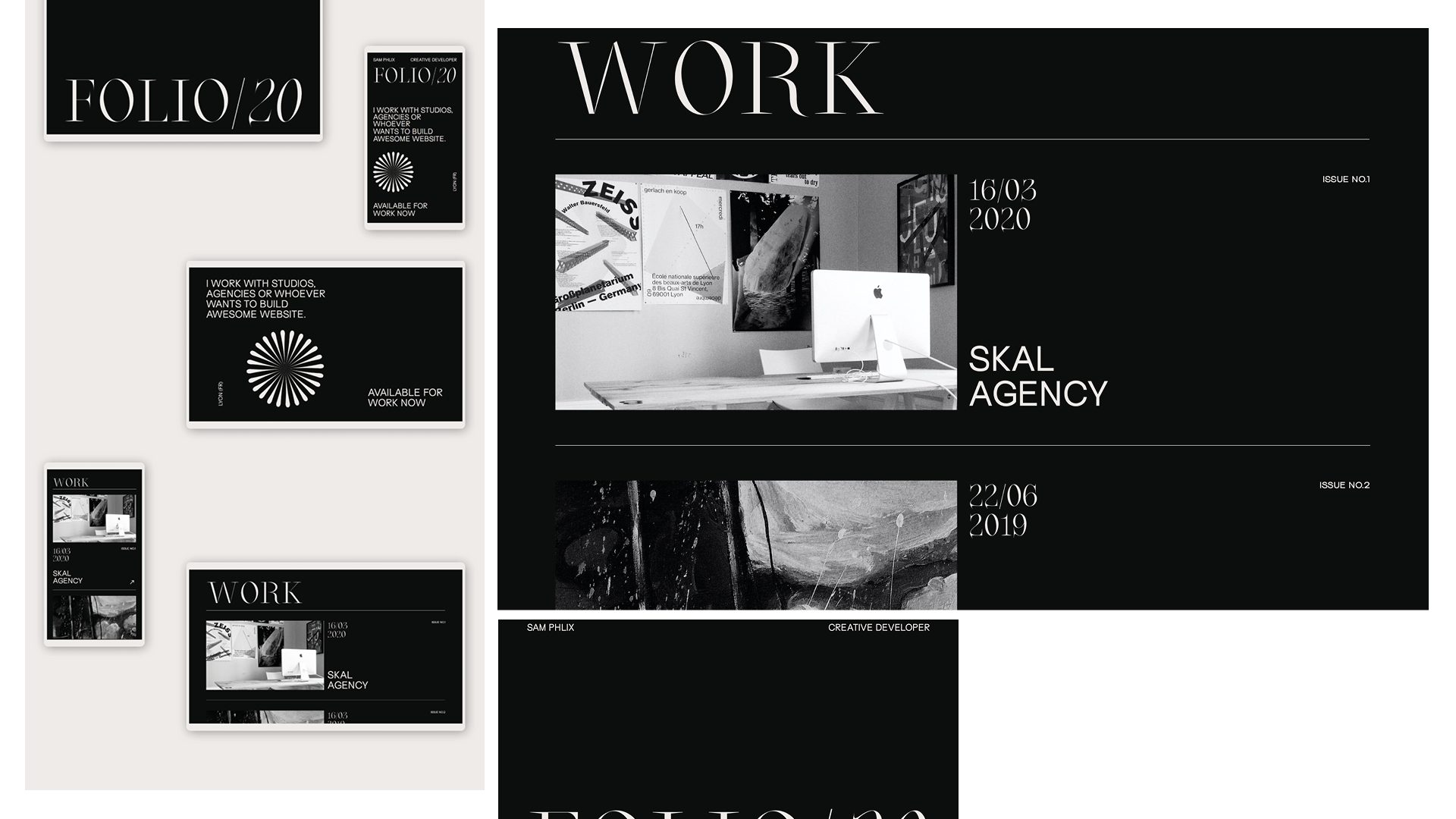

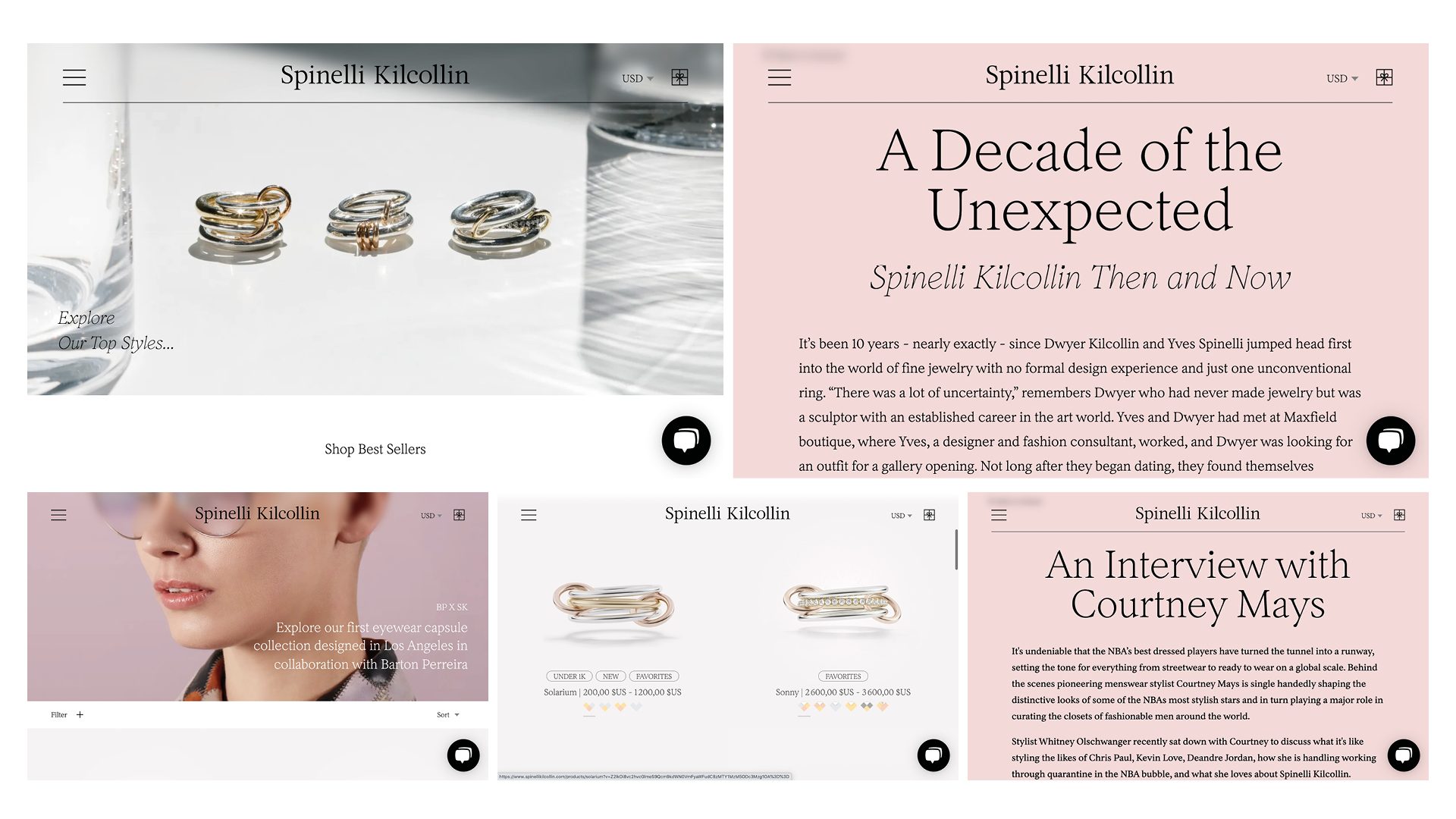

Smartphone for extreme reading

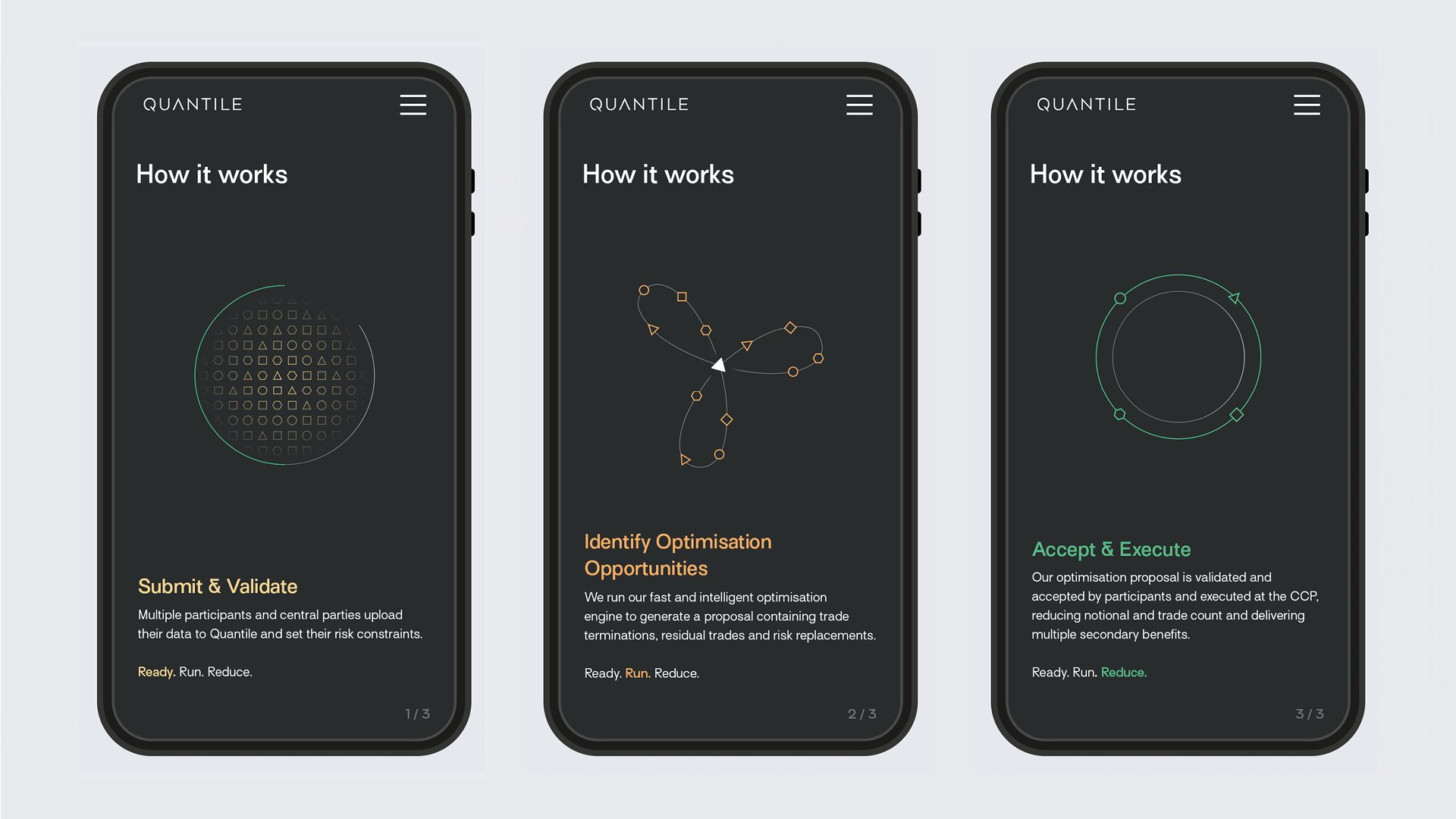

The limited space of the smartphone screen offers little freedom. Adaptation is therefore reduced to respecting the graphic identity, guaranteeing legibility, and optimizing ergonomics. The typographic palette must be reduced like that for the tablet format, while ensuring that the sizes of each level of information are legible yet different. Variations between capitals and lower case, as well as weights and inclinations, are just as important as variations in type size.

Surt seems to be preferred by our agencies for contemporary and functional designs, specially on small size screens.

Generally speaking, there's no need to worry about a smartphone website appearing more functional than graphic. Viewing a website on this type of terminal indicates that you want to get an idea of content, not of a company's mindset.

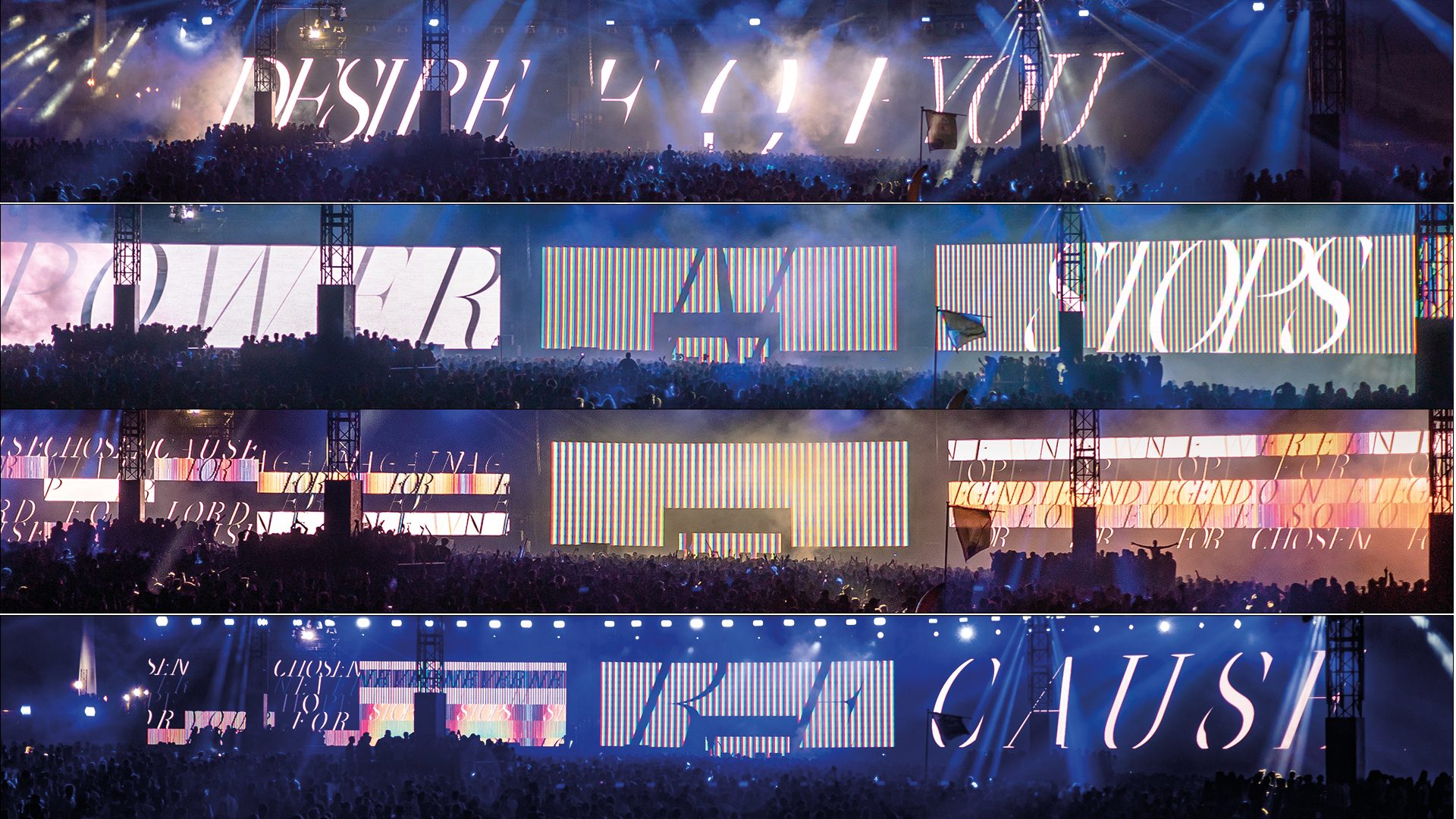

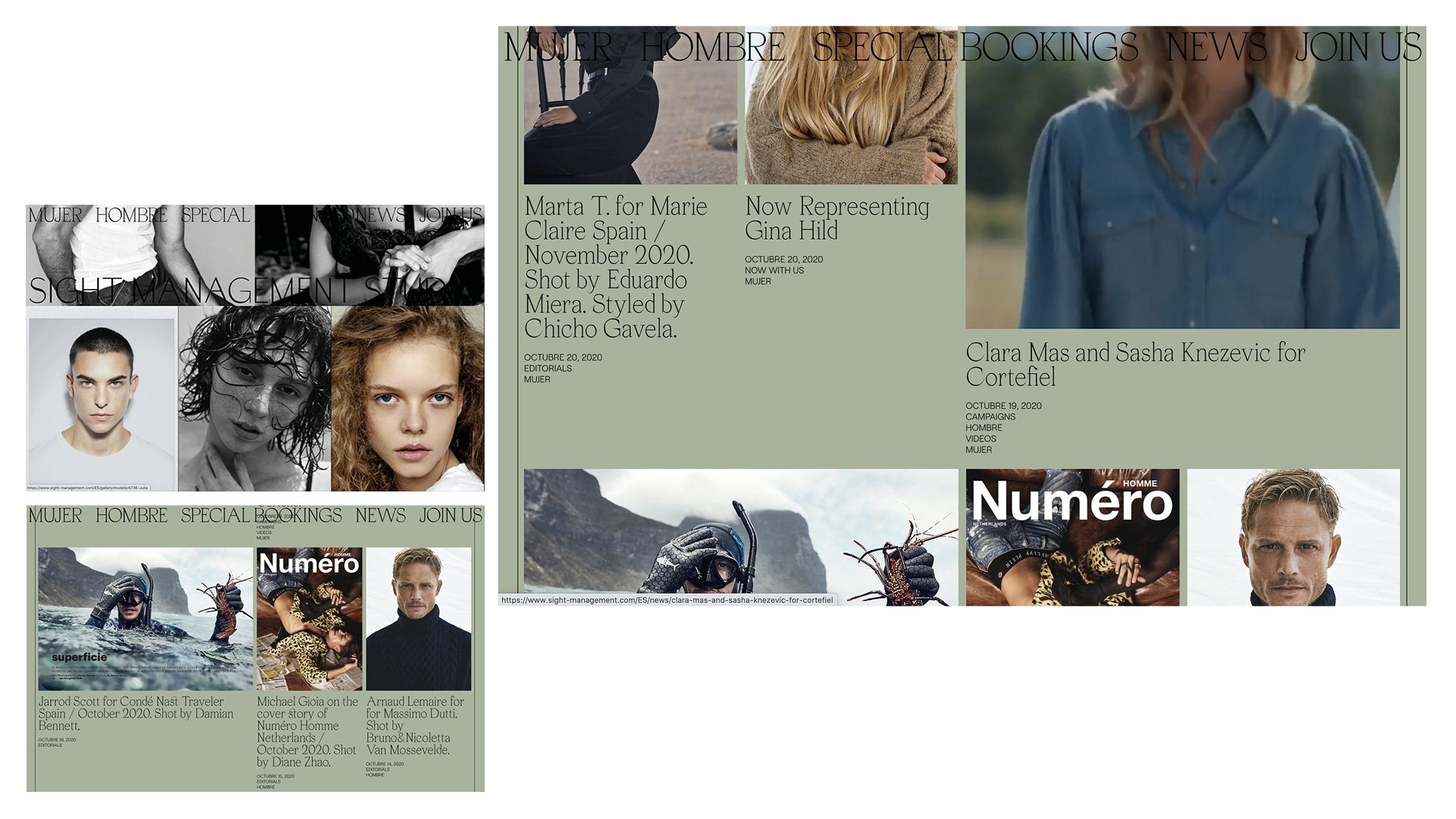

Wide Screen: the future of poster & signage

The case of large screens is a subject in its own right. Within this category, credits or video ads act like posters, with movement adding an extra dimension. The history of animated credits draws as much from the art of animated cinema (cartoons and stop motion) as from avant-garde and then commercial practices. From Saul Bass (credits for numerous films by Otto Preminger, Billy Wilder, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, John Frankenheimer, Martin Scorsese) to Kyle Cooper (Seven, The Island of Doctor Moreau, Mission: Impossible, Men in Black, Gattaca, The Avengers, Lost in Space, The Mummy, etc.), typography for credits has constantly reinvented itself through the formal games offered by technological evolution. The article on poster typography is therefore an excellent entry point for motion designers.

Credit design is a whole sprectrum in screen design.

Without going into too much detail, our streets are gradually replacing printed posters with video screens. Evolving technologies such as LEDs and electronic paper offer displays that are quicker and more convenient to update. Displays can be programmed by computer for time slots, customized frequencies and precise locations. Electronic paper displays (similar to e-readers) also save energy if they are fixed and long-lasting. Some technologies add interactivity to these devices with motion sensors.

The real innovation, since the urban screens will be nothing more than giant posters, is to be found on the video installation side, notably stage design for concerts or other cultural events.