. Published February 17, 2026

Apoc JP: making of Japanese

Introduction

Caio Kondo: After developing the Japanese extension of Area, on my first typographic translation project into Japanese alongside Matthieu Salvaggio, founder of Blaze Type, a new challenge emerged: translating Apoc into the kana system.

If Area was an exercise in structural adaptation, bringing a Latin sans into hiragana and katakana, Apoc required an additional level of complexity due to its far more expressive and dynamic nature. This was not merely about finding formal equivalences, but about interpreting a strongly defined personality: sharp, high-contrast, and charged with calligraphic tension.

In this article, I share my process in developing Apoc’s Japanese translation, explaining the structural, technical, and conceptual decisions that guided the project.

The Genesis of Apoc: Translating an Identity

What truly defines Apoc? Before designing, I needed to answer that question. The response emerged on three fronts: the aggressiveness of its terminals, the nervous tension of its curves, and an optical density that does not ask for permission.

While Area followed a geometric logic, Apoc demanded a more organic and calligraphic gesture. That instinct led me toward the Mincho style. I like to think of research as the foundation of a bridge: for the Latin and Japanese systems to coexist, style and structure must speak the same language.

But theory met a practical barrier: the delicacy of classical Mincho styles did not align with Apoc’s disruptive spirit. They were too refined; they lacked danger.

The focus then shifted to letter architecture. I used references to define proportions and spatial occupation, but with a clear directive: compactness. As Apoc is a display typeface, the kana could not feel airy. It needed to be dense, tactile, and visually cohesive with its Latin counterpart.

Proportion and Typographic Color

At this stage, references worked as structural compasses. I analyzed the balance between character size and side bearings, testing different Mincho styles. Among the options, Matthieu and I reached a conclusion: Reference E was the perfect match. Since Apoc is a display typeface with extremely tight spacing, E’s structure provided the necessary density to prevent the Japanese from appearing too loose alongside the Latin.

It was here that I made a crucial technical decision regarding typographic color. In Japanese design, the standard practice is to work within a 1000×1000 unit construction box, where each glyph occupies a fixed square. The Latin alphabet, on the other hand, is proportional: each letter has its own width.

To prevent the pairing between scripts from losing consistency, I decided to reduce the kana em-box to 980 units. This subtle metric compression was necessary to bring the two systems closer together, ensuring that the texture of the Japanese text carried the same visual impact and mass as Apoc’s Latin.

Building the Skeleton

As I defined proportions, I began drawing the skeletons. Unlike Area, where construction was more geometric and rational, Apoc required a different strategy due to its calligraphic complexity.

Instead of designing the entire Japanese syllabary at once, I focused on key characters. I imagined the process as a kind of genetic mapping: I needed to refine the structure and personality of these fundamental pieces before expanding the system. If those foundations were not perfectly calibrated, I risked propagating errors throughout the entire set. The idea was to create modular yet expressive components that could be adapted efficiently without sacrificing the soul of the design.

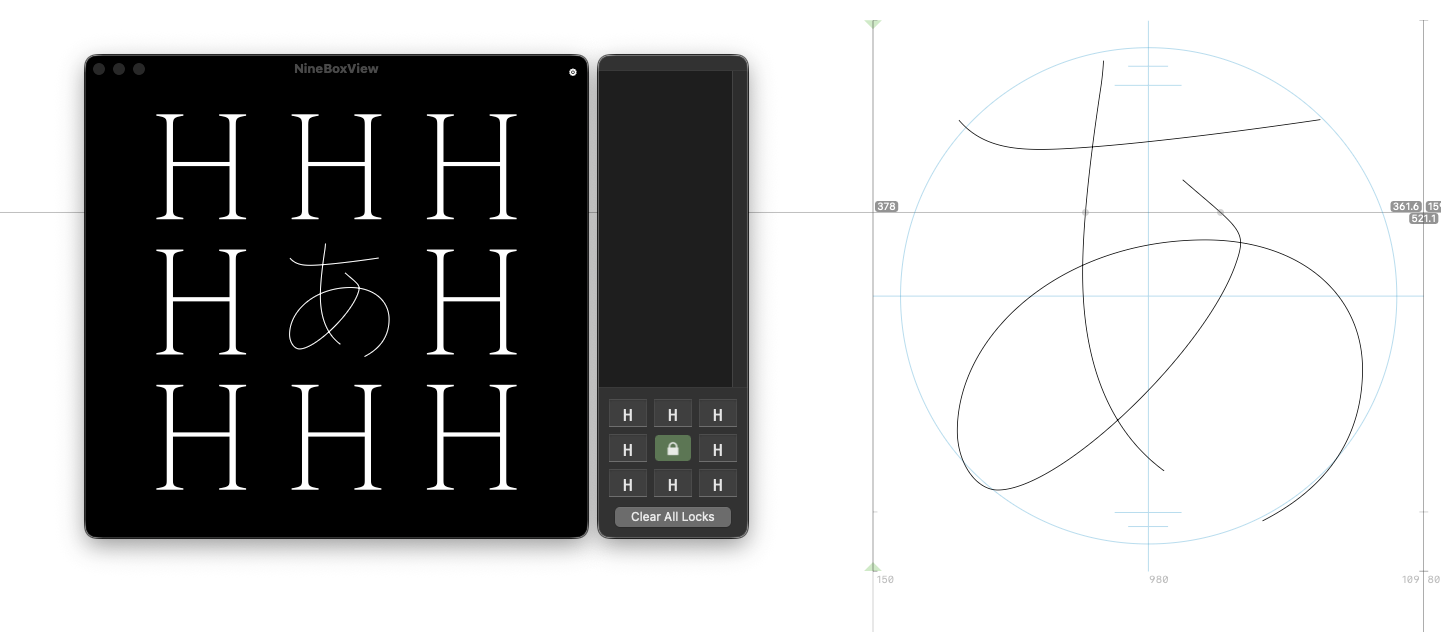

To parameterize central alignment, I relied on a visual metaphor that often helps me: I imagine Japanese letters as pieces of meat skewered on a barbecue rod. While the Latin alphabet rests on a baseline, Japanese characters float, requiring perfect central piercing along an axis. The challenge is doubled, since this optical balance must be precise both horizontally and vertically. To ensure this accuracy, I used the Nine Box View plugin in Glyphs, which allows the glyph to be viewed surrounded by neighbors in all directions. I used the Latin H as a constant reference; because it is a solid, rectilinear shape that fills almost the entire box, it served as the ideal frame to validate the kana’s volume and central alignment.

Inserting Contrast: Where Apoc Emerges

With the skeletons validated, the next step was applying contrast, beginning with the Light master. For this stage, I used Letterink, a tool I particularly enjoy for its precise gestural control, which is ideal for styles that preserve a calligraphic root.

At this point, the weights of the Latin alphabet served as a compass, but never as a strict rule. In multi-script design, there is a hierarchy of weight: Asian characters (kanji and kana) tend to appear visually heavier than Latin if drawn using exactly the same measurements. To balance the text color, I applied optical compensation, drawing the Japanese forms slightly thinner so that, in the end, both scripts would share the same typographic color.

Seeing the contrast emerge is the moment when the typeface stops being merely structure and gains identity. Apoc is defined by its sharp terminals, almost like blades. Translating this into Japanese required careful calibration: I elongated and sharpened the horizontals, controlled the weight at the extremities, and introduced additional tension into loops. I used the Latin A and a as my primary references, as they embody the essence of the family.

Working with skeletons may initially seem visually boring, but the final result compensates for every second through the speed and consistency it brings to the system. Once the key letters were properly “dressed,” the process became more dynamic and increasingly engaging. From that refined core, I moved on to structuring the entire character map. Having a solid foundation allowed the expansion to be fluid, ensuring that Apoc’s cutting personality was present in every new glyph added to the set. Throughout the process, I continuously refined the forms to validate structure, personality, and contrast.

Expanding the Weights

With the lightest master finalized, I began the journey toward the heavier weights. If precision defined the Hairline, in the Dark the challenge shifted in scale. Expanding weight is not simply about thickening strokes, but about managing a far more aggressive occupation of space.

At this stage, four major challenges guided every decision: avoiding excessive closure of counterforms, preserving the sharpness of the serifs so they would not lose their “cut,” maintaining consistency in optical gray across different weights, and ensuring technical compatibility between masters for seamless interpolation.

The construction of the Dark directly mirrored the Hairline process. I replicated exactly the same workflow: starting from the skeleton, refining the key letters, and then expanding the rest of the character set.

Verticality

A Japanese typeface does not consist only of horizontal writing. I carefully reviewed the behavior of each glyph in vertical composition, where alignment logic and punctuation positioning change. Punctuation marks require specific adjustments, shifting to the upper-right quadrant of the box. While Latin characters typically rotate 90 degrees to follow the vertical flow, Japanese glyphs remain upright.

All of this mechanics was consolidated through OpenType programming. This technical refinement is essential to ensure that the typeface performs flawlessly in native software and strictly adheres to vertical composition standards, guaranteeing fluid reading in any direction.

The Challenge of Diacritics: Tenten and Maru

Like diacritics in the Latin alphabet, the kana syllabaries use the Tenten (dakuten) and the Maru (handakuten). Positioning them is an exercise in spatial engineering: the variety of forms within the em-box is vast, and the available space for these marks is limited. In several moments, I needed to subtly modify the structure of more spacious characters in order to accommodate the diacritic without breaking visual harmony or creating weight conflicts.

Specimen and Collaboration

For the launch of Apoc JP, María Centeno was invited to develop the project’s visual pieces. María has a very distinctive visual language, and in this project she explored a raw and gestural expressiveness that entered into direct dialogue with the spirit of the typeface.

From the outset, we wanted to avoid obvious narratives. Although this was a translation project into Japanese, we deliberately sought distance from any aesthetic cliché or predictable reference.

María’s analog process shifted the project away from the conventional territory of purely digital specimens. The work was essentially tactile: she intervened directly on printed compositions, merging graphite textures and manual shading with the typographic forms. The results speak for themselves.