By Sebastien Hayez. Published June 21, 2022

The story of the Ampersand

Introduction

A character, a letter of the alphabet, an ideogram? The ampersand can be a mystery to the public as well as to the novice graphic designer.

Traditionally, English schoolchildren used to recite the alphabet, focusing on vowels that could be heard as independent words: A, I and O were mentioned, followed by the Latin phrase per se, meaning "by itself". This kind of rhyme ended with "X, Y, Z, and per se and": ampersand. Thus, from 1837 onwards, the & entered the English language as the 27th letter of the alphabet.

However, this graphic sign is not alphabetical.

French uses the word ampersand (with a host of possible spellings, such as esperluète, éperluette, perluette, perluète), but, like English, it means "et par lui, et", the second et being pronounced as in Latin, "ette".

Ancient origins

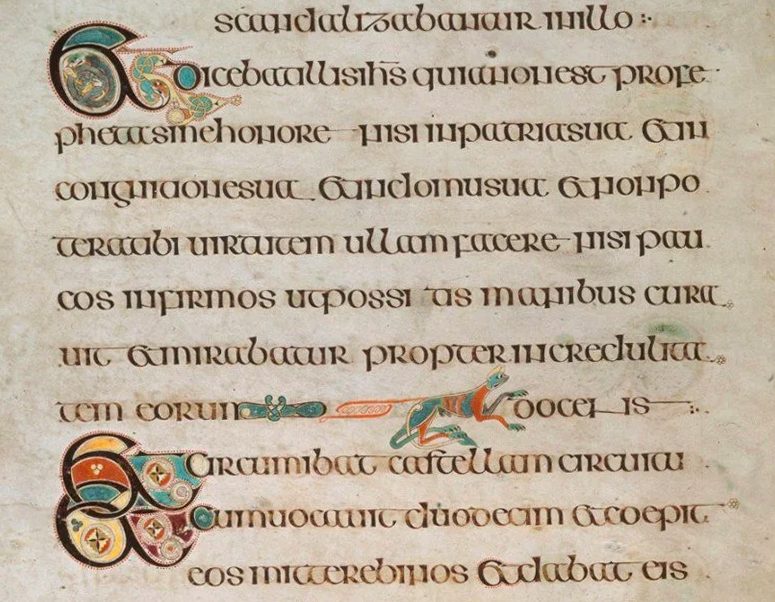

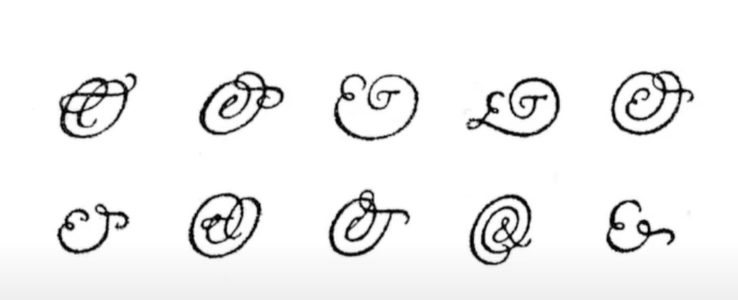

The Roman lapidary writing may have served as a model for our Latin capitals, but it coexisted daily with cursive forms still visible on the graffiti of the time. The scratched and hurried nature of these writings implies to reduce the ductus to the minimum of stylus strokes, thus favoring the ligature set. This is how the coordinating conjunction "and" came to be traced through different styles giving birth to some of the current forms of our ampersands.

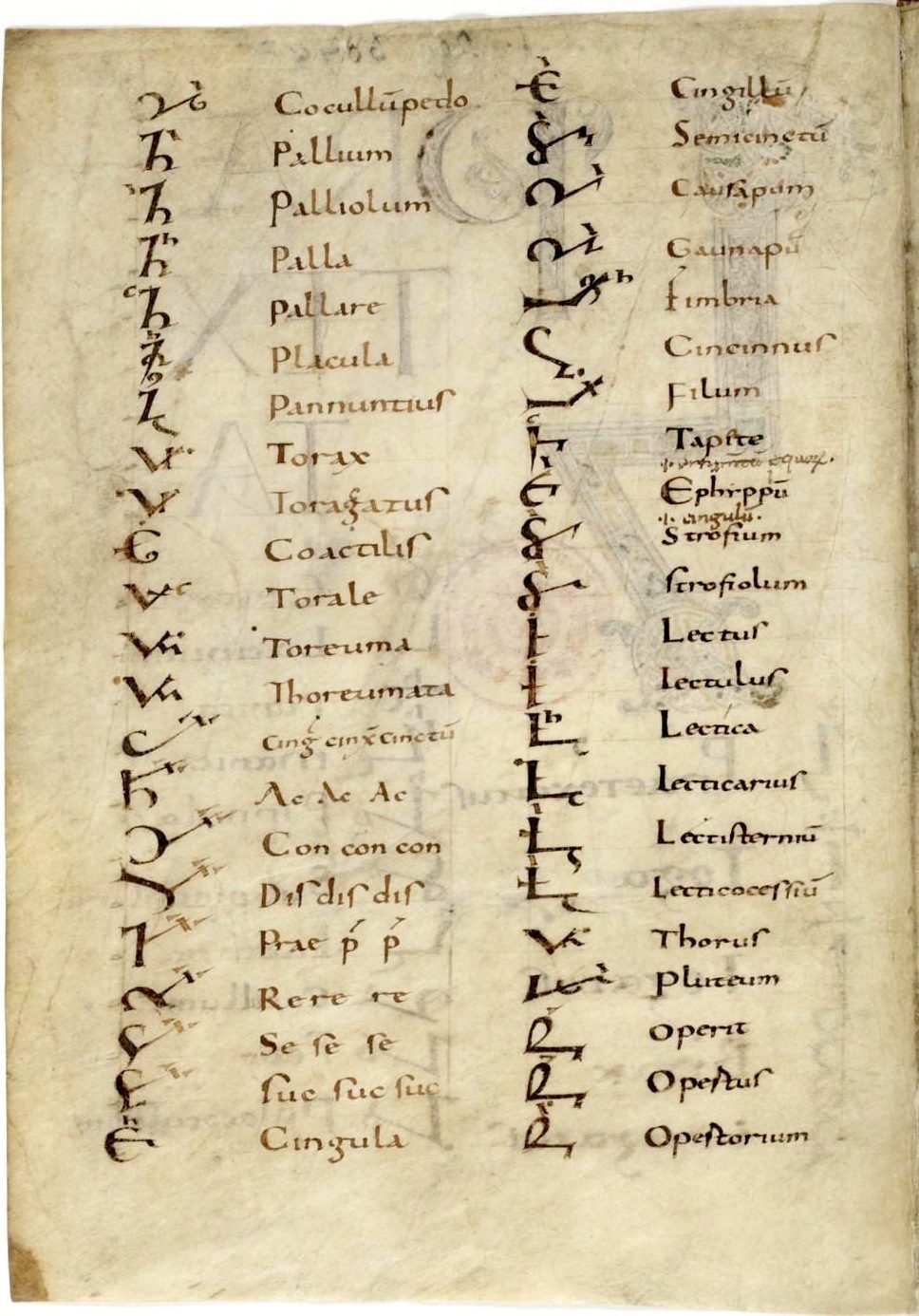

However, the ampersand in its ligatured form is not used exclusively during the antiquity period. In uses related to diplomacy, in particular to notarial documents, another system of sign is in use. Invented around 63 B.C. by Marcus Tullius Tiro, a freed slave of Cicero who became his secretary, the Tironian notes are a system allowing the rapid transcription of speech. Paleographers define it as a tachygraphy system. In its initial purpose, it is comparable to contemporary shorthand writings, but also offers the advantage of encrypting documents for the uninitiated, since the system contained 4000 signs at its creation, to expand to 14000 signs during the Carolingian period.

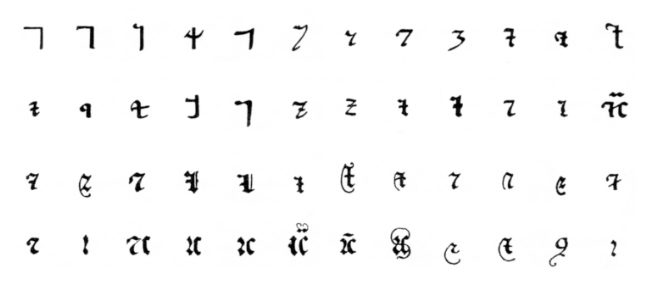

The Latin et is written in the form of a right angle similar to the spelling of the 7, sometimes accompanied by a horizontal crossbar. Its morphology is extremely simplified and includes some features of the ET ligature.

Medieval use

Its use during the Middle Ages spread in notary offices but also in monasteries since the advent of the Caroline script. Charlemagne asked to standardize the design of the letters in order to propose a script cleansed of national particularisms, symbolically uniting the peoples around a political and graphic figure. For this reason, the ligatures put aside are substituted in the contexts reserved for certain functions by the tironic notes. Around 800, the tironic ampersand thus experienced a revival of interest while the & remained one of the only ligatures allowed in Caroline. The & is thus found until around 1200 in careful writings while the tironic note is more visible in documents and working manuscripts, some monks using one or the other without distinction.

Always considered as a ligature of digrams et, the & and its tironic note can enter in the composition of a word: "proph&a" for propheta, “&c” for et cetera, for example.

However, in the British Isles and non-Latin countries, a distinction is made: the & still corresponds to the ligature et, corresponding to the Latin coordinating conjunction, while the tironian note becomes the vernacular form for the Irish agus, the Anglo-Saxon ond, or other forms of local coordinating conjunctions.

Around 1200, the appearance of the Gothic script favors the tironic form in order to translate the vernacular conjunction, and makes this sign popular until the 17th century in France and elsewhere, and until the 20th century in Germany.

Until 1230, a transitional period even saw the two signs coexist by establishing the tiron note as a lower case, while the & represented a capital form. But from then on, these two signs symbolized the conjunction and not the Latin and. In this way the & becomes a logogram, a graphic sign representing a word.

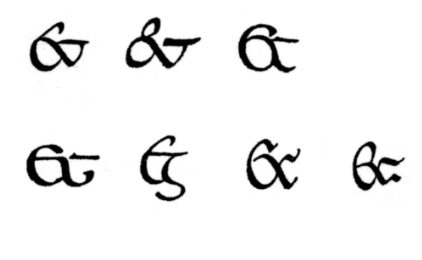

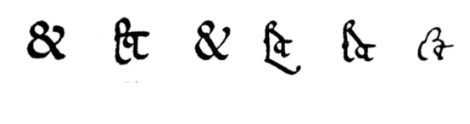

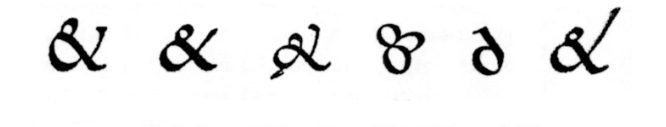

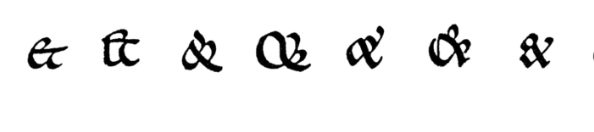

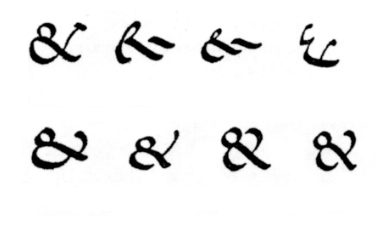

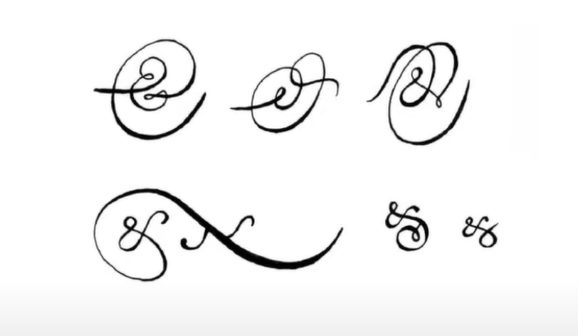

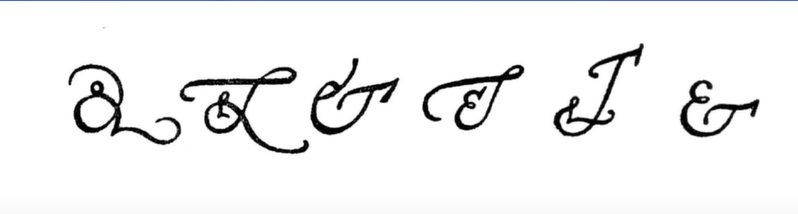

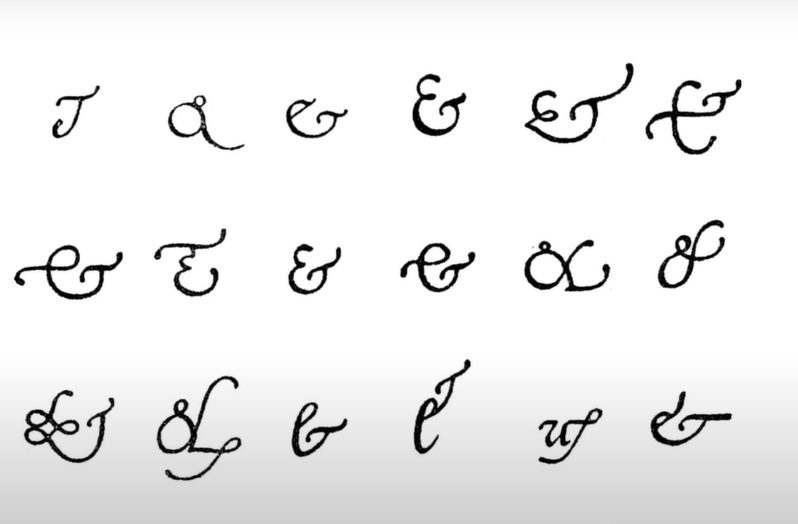

Around 1400, the Renaissance brought ligatures back into fashion and kept the & as the logogram of the conjunction. Thus, the strokes are going to free themselves to propose new forms. The cursive italic writing offers more animated and fluid variants, while the sign can be seen as an ornament of the page demonstrating the talents of the master writers and calligraphers of court.

Modern & contemporary development

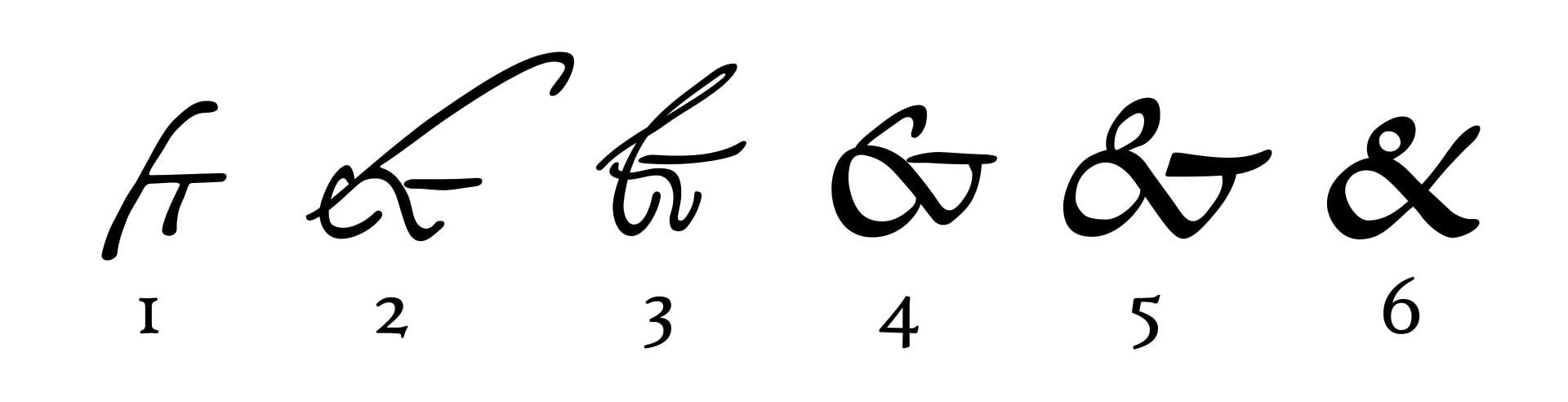

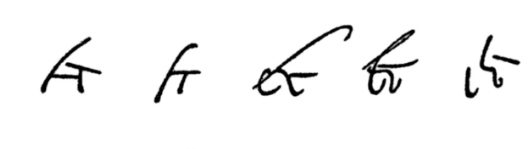

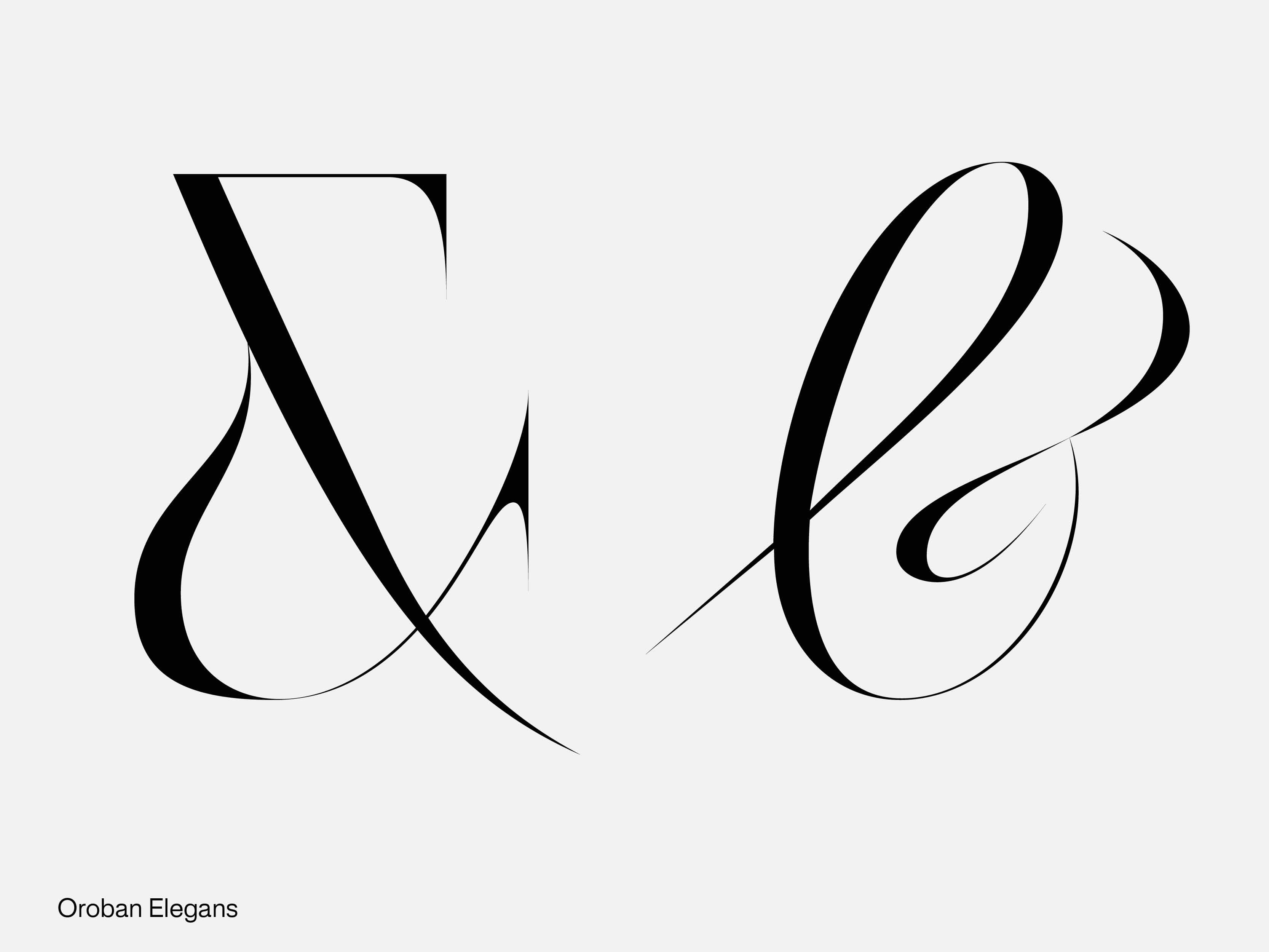

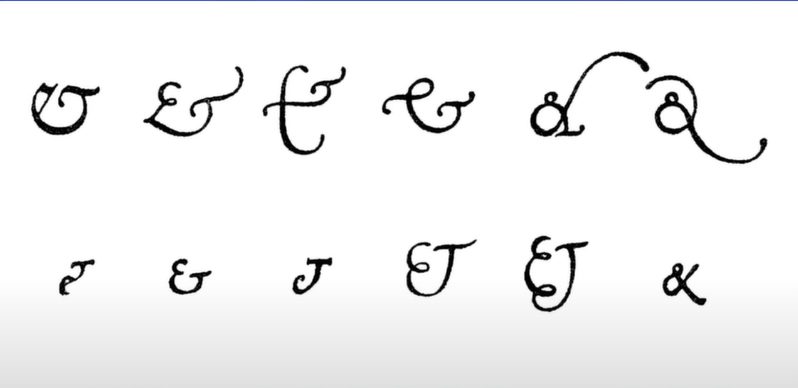

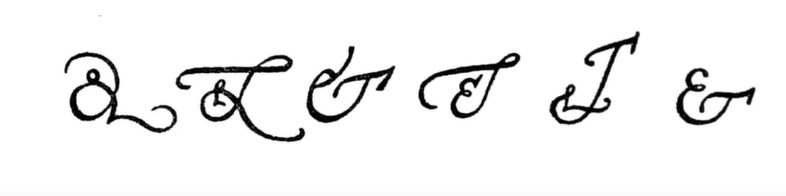

It would be tedious to draw here the evolution of the & in its different styles since the Antiquity. Obviously, it follows the evolution of writing itself, via the evolution of techniques related to tools and supports. Jan Tschichold realize this task with care in 1953 in his book Formenwandlungen der Et-Zeichen, still published in English and French. The main images are shown here, the detailed captions are available in the various national editions.

If one returns to the name of this sign, it is the commercial use which appears: the French sometimes use the name of “commercial and” so much it appears in the commercial name of big companies. It is difficult to date the generalization of this appearance. The commercial development of trade marks at the turn of the XIXth and XXth centuries sees the companies enduring from father to son in order to prolong the family success. Partnerships, like mergers between competing companies, see the commercial name take on the scope of several names linked by a conjunction. In all these configurations, it is the names that must be read, the conjunction must be understood. Thus the & becomes almost the literary image of a +.

Moreover, its handwriting stroke, forgotten for centuries, is not taught to schoolchildren. How can it be depicted?

The decomposition of the sign illustrates a capital E understood as an epsilon crossed by a vertical bar. The simplification of the ductus, in a concern for efficiency as well as a misunderstanding of the original sign, makes it an epsilon with vertical extensions. Finally, the + sign is sometimes written in a way that can evoke a lower case e coupled with a cross t.

Learn more:

Jan Tschichold, A Brief History of the Ampersand, -Zeug, Paris, 2017 (The book comes with an afterword by Marc H. Smith, also a great source for the history of the @ sign)

Attention ça glyphe (french only)

Emilie Rigaud added some personal content on the Tschichold text.

About the author

Sébastien Hayez was an art director and graphic designer before becoming an art teacher and an independent researcher in the field of graphic design and type design history. His main topics are the history of logos, square books, modernism, and the minimalist italian designer AG Fronzoni 1923-2002. You can read his contributions in the pages of magazines such as Etapes, TheShelf Journal, Pli, Kiblind, Yellow Submarine, Fiction, or listen to his lectures for Les Rencontres de Lure or Fonts & faces #7.