By Sebastien Hayez. Published April 22, 2025

Stencil: an avoided history | 1/2

Principle & generalities

The walls of prehistoric caves are filled with the hand silhouettes of our ancestors. Aside from the question of identity, the reproduction of these silhouettes involves a number of complementary processes:

- The imprint is obtained by transferring the clay covering the hand-matrix to the wall, creating a positive shape;

- The impression is obtained by spraying diluted clay all around the hand with the mouth, creating a negative silhouette.

Applied to the printing process, the positive hand corresponds to relief printing, and therefore to movable type, while the negative hand illustrates the stencil principle.

Believing that stencils are reserved for minor decorative purposes is highly simplistic, but less so than believing that typography is not compatible with stencils. As proof, more common than neon letters, illuminated letters appear on a lightbox, obscuring the empty spaces.

However, stencil printing does require a number of adjustments to make it effective.

The first is structural, since the cutting of the design to be printed makes it impossible to keep a counter-form integral with its shape: the central void of the O is no longer integral with its outer silhouette, and to do this properly, it would have to be held in place during printing or reattached using bridges. The first option is not possible, as it would be time-consuming and imprecise. The second, however, has been rapidly implemented in ornamental stencils, both in the West and in the East, notably by the Japanese (katazome).

The stencil is therefore relevant for several reasons:

Size: adjustable in size, as long as the stencil matrix is large enough (mostly made of leather, metal or paper).

Placement: placement is manual and allows multiple adjustments so that each matrix becomes a pattern or a module within a more complex pattern.

Quantity: the matrix is strong enough to withstand large reproductions, but manual application involves few reproductions.

Color: as the matrix is not printed, color changes are quick and easy.

Medium: paint is preferred to ink. The art and decoration trades are more likely to use it, since it benefits from the same materials.

Substrate: flexible or non-porous substrates are possible, unlike printing with fatty inks.

These features make stencil printing a preferred process for ornamental and decorative graphics. The etymology of stencil is particularly illuminating in this respect. Stencil (1848) is the contemporary form of stanesiler (1707), probably developed from the Middle English stencellen meaning to adorn, or color (before 1400), itself borrowed from the Middle French estenceler, to cover with sparks or stars, with colored powder. The whole is derived from the vulgar Latin stincilla, meaning spark.

Historians have noted that the practice dates back to ancient Egyptian times, when papyrus leaves were added to decorate ceramics with motifs, and to the Middle Ages, when they were used to decorate castle walls, fabrics, banners and tournament flags.

Standardized writing: between craft and industry

Prints or stencils, both operate according to the same logic: a matrix form enables a design to be printed by full or recessed transfer. It's inconceivable that stencilling is a heritage limited to one continent. The most difficult thing is to find traces of such use, when the crafts are taught orally, and the decorations that have come down to us are few and in poor condition.

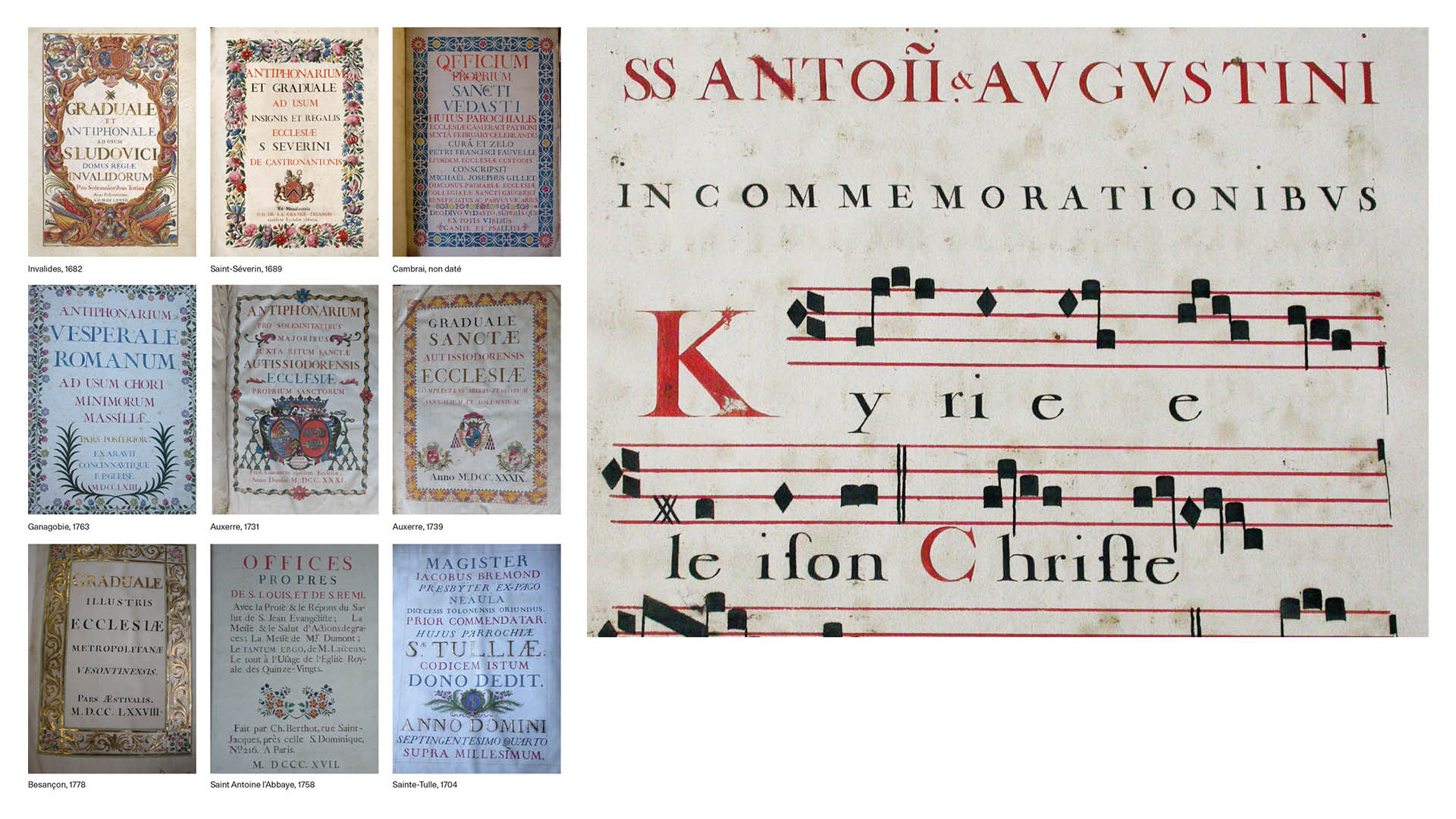

Stencilled wall ornaments and textiles probably lasted beyond the medieval period. However, it wasn't until the mid-17th century that stencilled texts came to light. Numerous French and German liturgical chant books, known as "livres de chœur", were displayed on a lectern during mass. The exceptional nature of such editions, with their monumental format (80 by 110 cm), their weight (up to 30 kg) and their content specific to a place of worship, implies a unique manufacturing process. While calligraphy is time-consuming and its artists rarer, stencil printing appears to be a compromise between writing and letterpress printing. The final result is highly precise, even if breaks in the letters have to be retouched with a pen to respect the usual appearance of the glyphs. However, the trend is moving towards a form of tolerance, and these shortcomings are no longer filled in, probably for reasons of cost and time.

In the 18th-19th centuries, the process proved preferable to movable type printing, particularly for city works (visiting and business cards) and bookplates. Presses reserved for publishing were unsuitable for short print runs and the marking of ready-to-use objects (account books, poster headers).

The nascent industrialization of the early 19th century meant that bales, crates and boxes had to be marked all over the world. Here again, the stencil appeared as a standardized letter, easy to apply to a variety of materials (paper, wall, wood, metal, textiles, ceramics and glass) and by unskilled personnel. In short, logistics marking is a stencil applied to containers or the goods themselves. At the beginning of the 19th century, several processes were used in the United States, most of them metal cards with individual glyphs hinged at the ends. However, each company marketed its own system according to patent registrations. For example, a copper disk stencil was registered in New York in 1868 by Eugene L. Tarbox.

In 1870, the universal engraved plate (J.A. David) enabled lettering to be prepared using a stencil containing all the glyphs on a single metal plate. This advanced normograph was marketed in France and the USA at the Paris Universal Exhibition in 1878.

Openwork writing: manufacturing processes

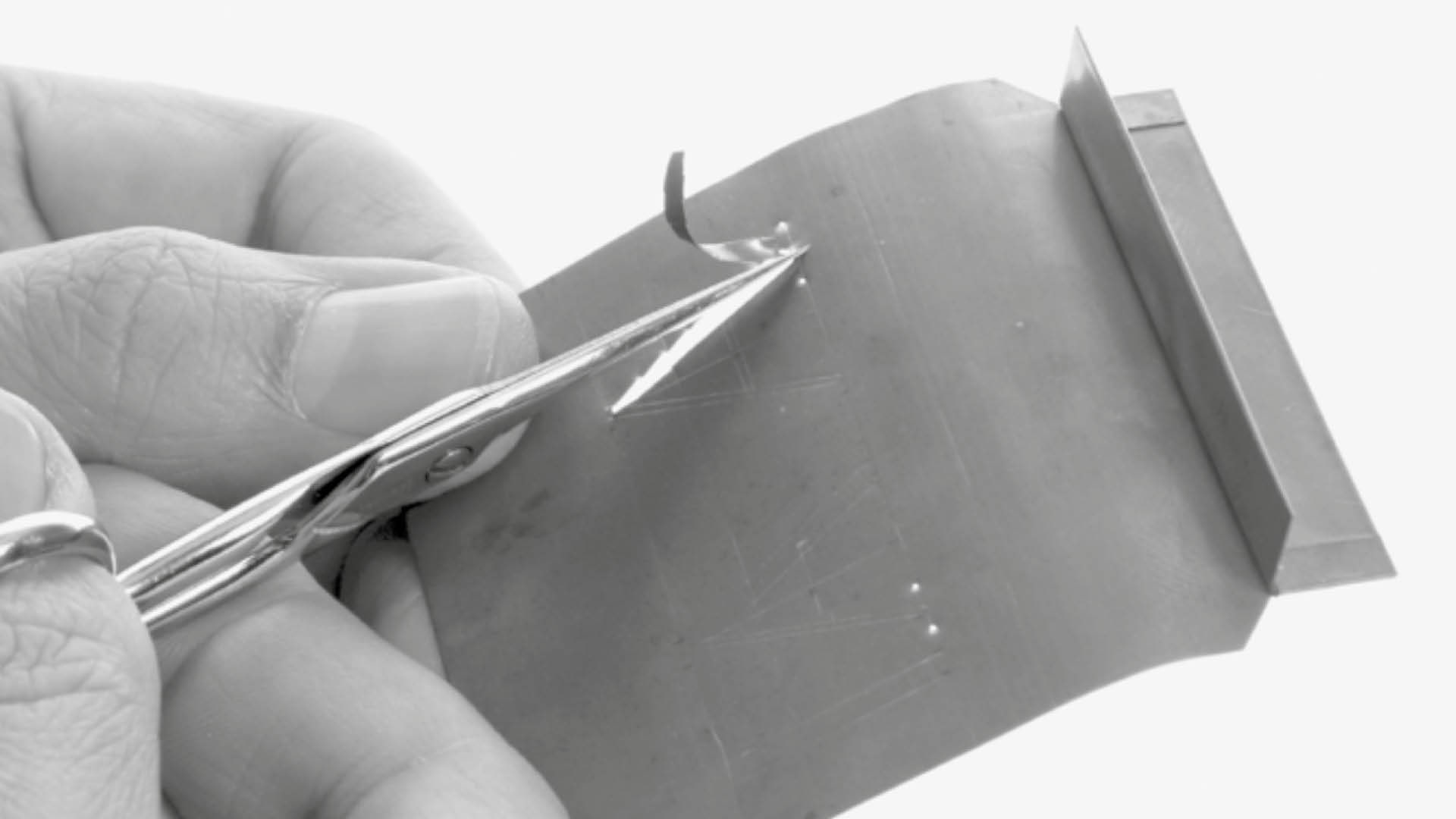

Cutting with scissors

The process of typographic reproduction using stencils is largely handed down to us via Gilles Filleau des Billettes (1634-1720) and his relative entry in the pages of Description des Arts et Métiers (1761-1782). The scholar, and encyclopedist, details the tools and steps required to obtain brass stencils and put them to good use.

The glyph design is transferred to the metal plate with a metal tip, then cut out with a pair of scissors. The edges are then trimmed and polished to refine its contours.

Each card features a glyph sometimes broken down into several modules (the a, into a belly and its barrel curved into a drop), accompanied by a "lumière (light)", i.e. a rectangular opening on the left allowing you to decide which way to kern the text.

This procedure seems to be common for quality markings, whether in choir books or on walls.

Credit: Eric Liddle

Engraving cutting

Small stencil specimens highlight a more precise technique. The glyph design is transferred to the metal plate, which is then covered with a protective varnish, except for the shape of the glyph. Thus protected, the plate is dipped in an acid bath and the etching process, similar to that used by art engravers, allows the plate to be perforated. Here, the aim is not to deliver one typeface per plate, but to create a matrix for a complete layout. In this way, reproduction of a business card or bookplate in multiple copies is made easy, fast and possible on demand.

This was the process used in towns before the advent of small hand presses.

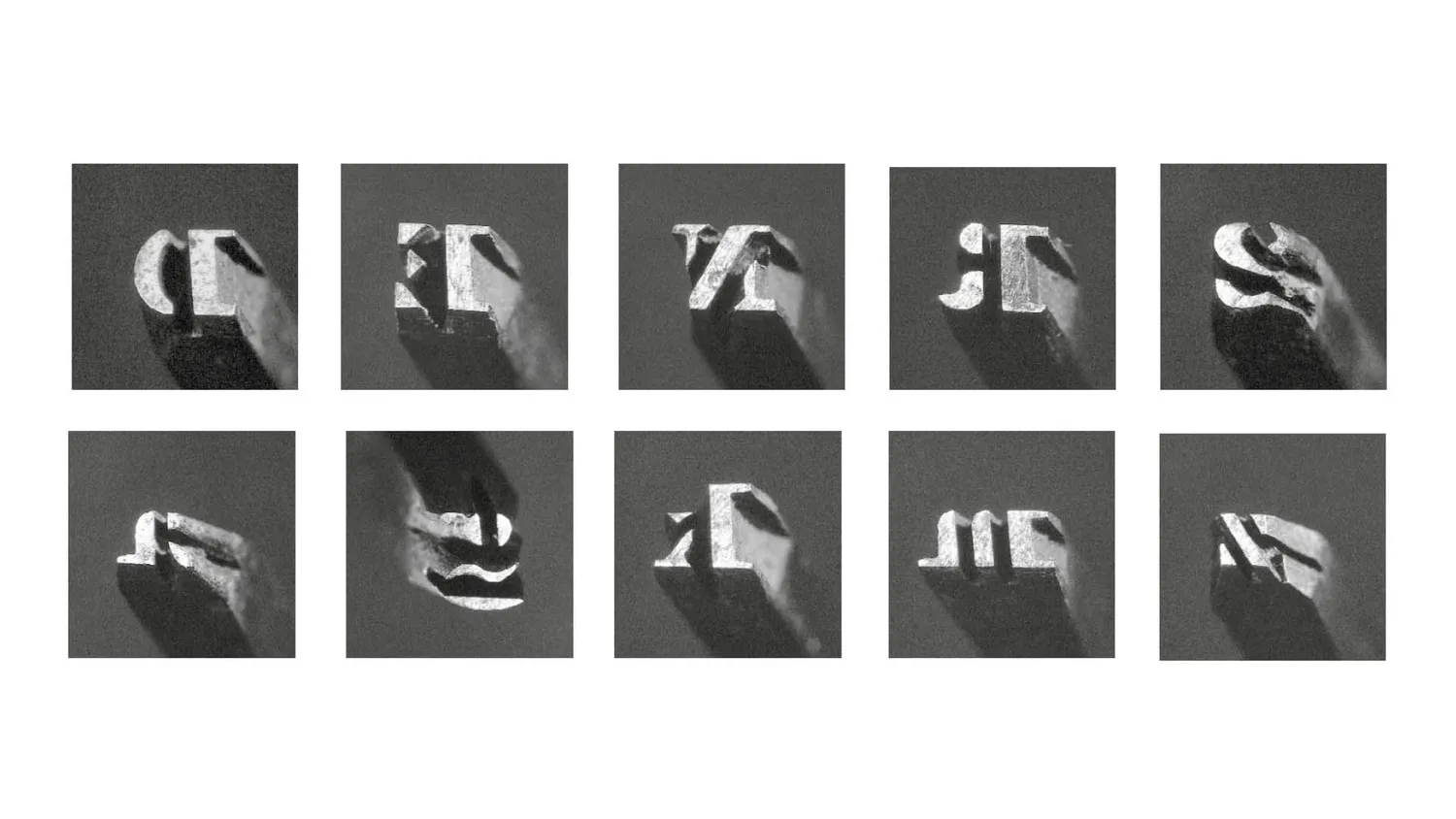

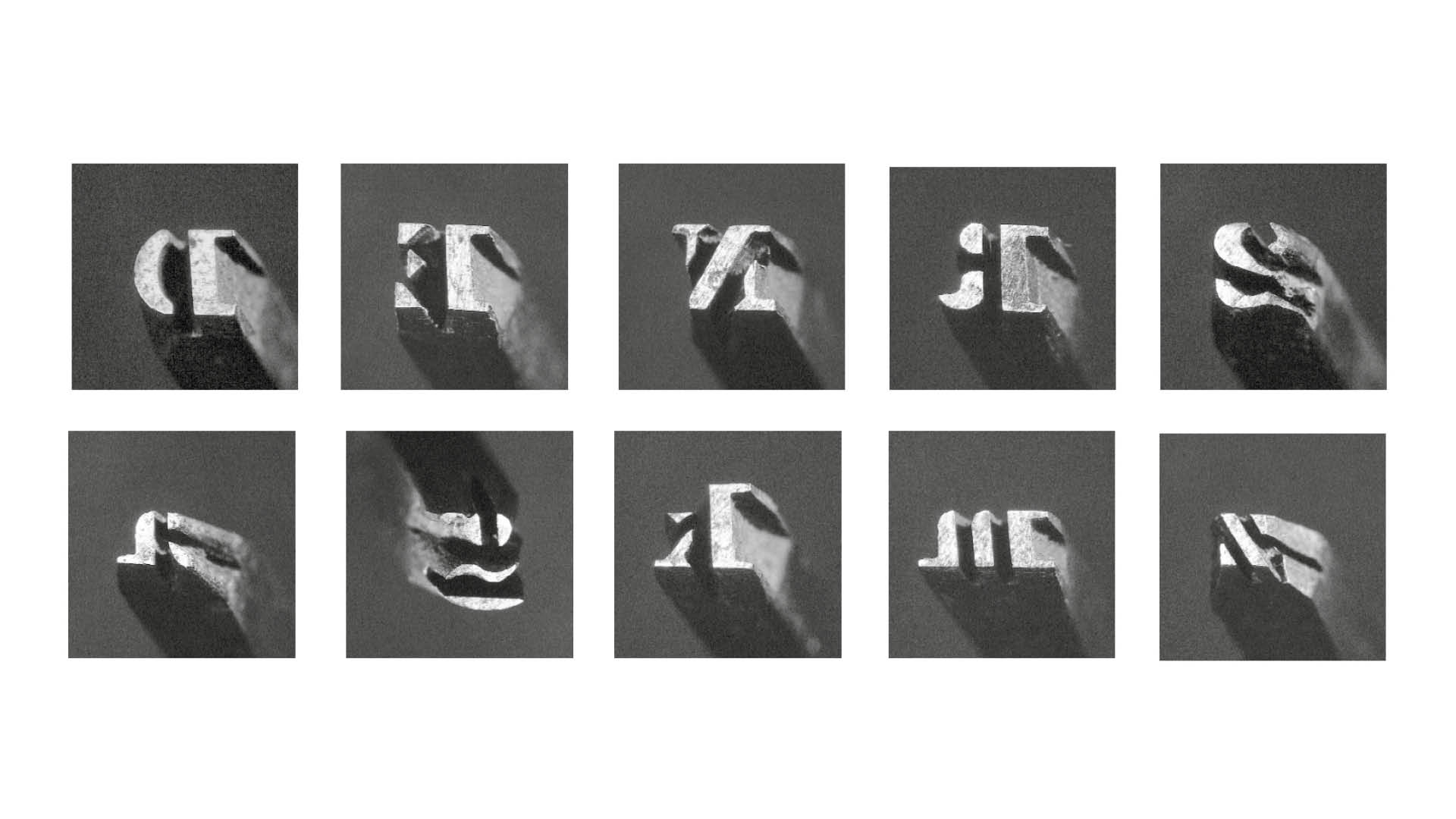

Punch cutting

The characters are melted down to obtain individual punches with the necessary breaks and bridges for stencils. The metal plates are then struck with the punches to produce as many plates as required.

This process seems suited to mass marketing, which has been found since the early 19th century in the major industrial countries (USA, France, UK, Germany) and reserved for logistical and industrial marking. This process tends to simplify the design of the letters, both in terms of geometry and extreme slenderness. The result largely prefigures Art Deco alphabets such as Futura Black.

Credit: Eric Liddle

This article is immensely indebted to Eric Kindel's decades-long research. Short texts accompanied by lectures provide a rough but meaningful picture of the everyday use of stencil letters.

- Recollecting Stencil Letters

- Reconstitution of techniques from Billettes

- The stencilled poster in Paris in the 19th century

- Eric Kindel - Objet-type, the French Stencil Letter

- Plaque de découpe Universelle

- "Marked by time", Eye 10, Summer 2001, 48-51

- "Stencil work in America 1850-1900", baseline 38, Summer 2002, 5-12

- Histoire de l'écriture typographique, Le XVIIIe siècle, tome ½, les écritures réalisées au pochoir, Claude-Laurent François. Dir. Yves Perrousseaux, Atelier Perrousseaux éditeur, 2010, pp.48-75.

- Histoire de l'écriture typographique, Le XXe siècle, tome ½, Sociologie et renouveau d'un caractère : les pochoirs, Jacques André. Dir. Yves Perrousseaux, Atelier Perrousseaux éditeur, 2016, pp.72-87.

- Richly documented with lots of images of equipment

- Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

- List of historical stencil fonts by country

- Stencil, etymology and history of the image printing process

- Short article by Heller & Filli with nice examples

- Medieval stencil decoration

- https://anrt-nancy.fr/en/projets/stencilled