By Sebastien Hayez. Published August 22, 2022

Graphic Design: Posters from Japan

Introduction

Since the late 1960s, Japan has invaded the world with a culture made of computers, hi-fi, cars, video games, manga and anime. Already in 1970, Roland Barthes (1915-1980) wrote in The Empire of Signs: "The author has never, in any sense, photographed Japan. It would be rather the opposite: Japan has starred him with multiple flashes; or better still: Japan has put him in a writing situation." . Barthes knows well that what he tries to analyze is more his perception of Japan than Japan itself. Through his Western culture, he remains the victim of an exotic gaze, that is to say, is external to his own place (I invite you to reread the chapter devoted to the eyelid in order to realize the racist and colonial clichés still in force in 1970).

So, how to approach the Japanese poster without falling into value judgments or absurd generality? Let's accept our western vision and let's rather highlight the reciprocal influences between the country of the Rising Sun and a protean West.

Ukiyo-e : image of the floating world

Japan has been under the influence of Chinese culture for a long time, be it politically, culturally or artistically. It was at the beginning of the Edo period (1603-1868), thanks to a more stable political situation, that commerce and urbanism developed, creating a class of craftsmen and merchants who were richer than before. This economic and commercial development is asserted in a wide range of cultural practices, including poetry, theater and of course painting and printmaking.

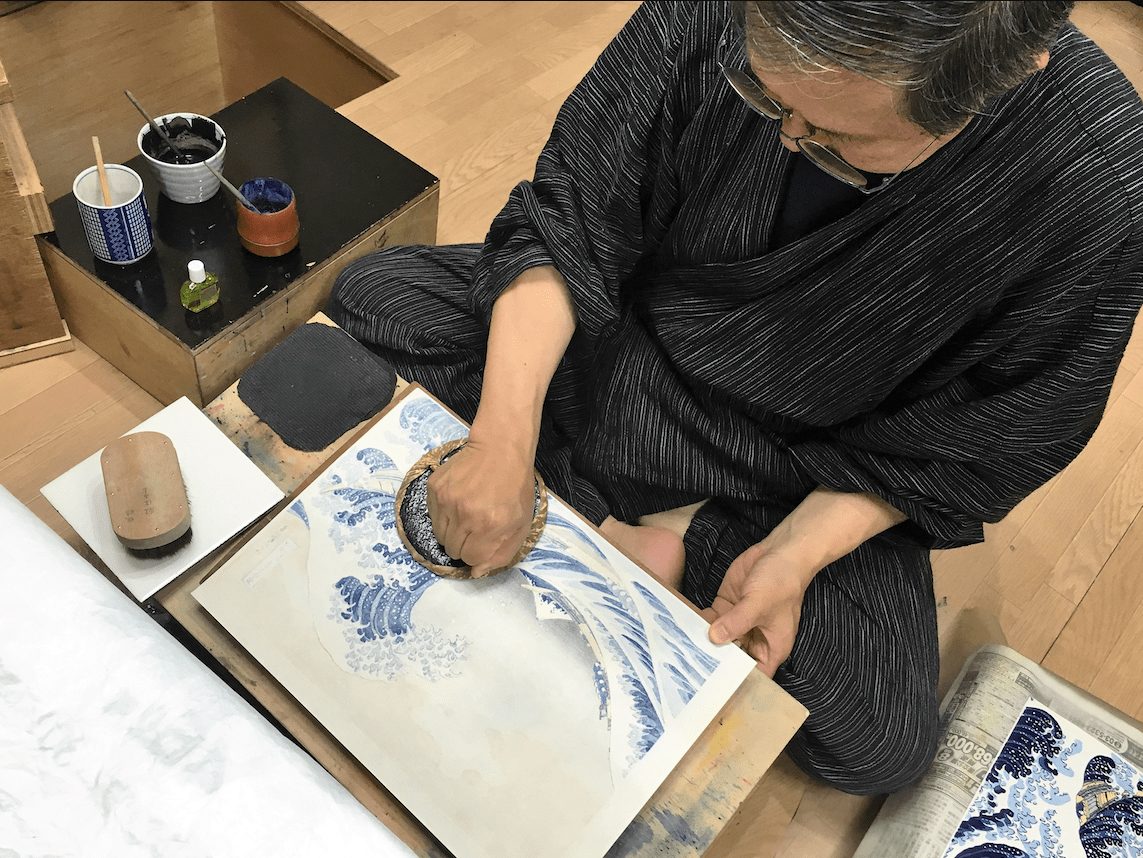

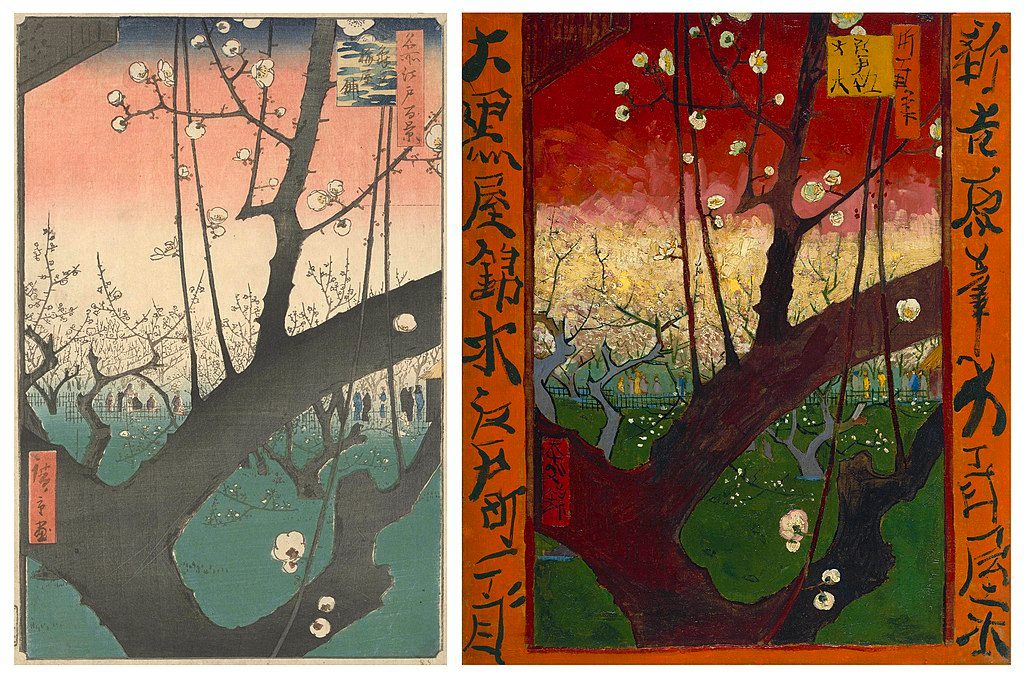

Ukiyo-e, literally image of the floating world, is a school of paintings and prints typically Japanese but mostly popular. The technique is also known in the West at the same period, it is woodcut (along the grain): the matrix of wood is incised and engraved in the direction of the fiber of wood, then inked and pressed on a sheet of paper. Requiring rudimentary equipment, both for its realization and for its printing

Ukiyo-e allows at low cost to multiply the prints as long as the engraved plate resists the passage of the baren (a stamp of bamboo leaves pressing the back of the sheet). 300 copies seems to be a maximum print run that still spares the wooden matrix.

Mainly used in book illustration, Ukiyo-e is freed from the text when the loose sheets (ichimai-e) or the posters of kabuki.

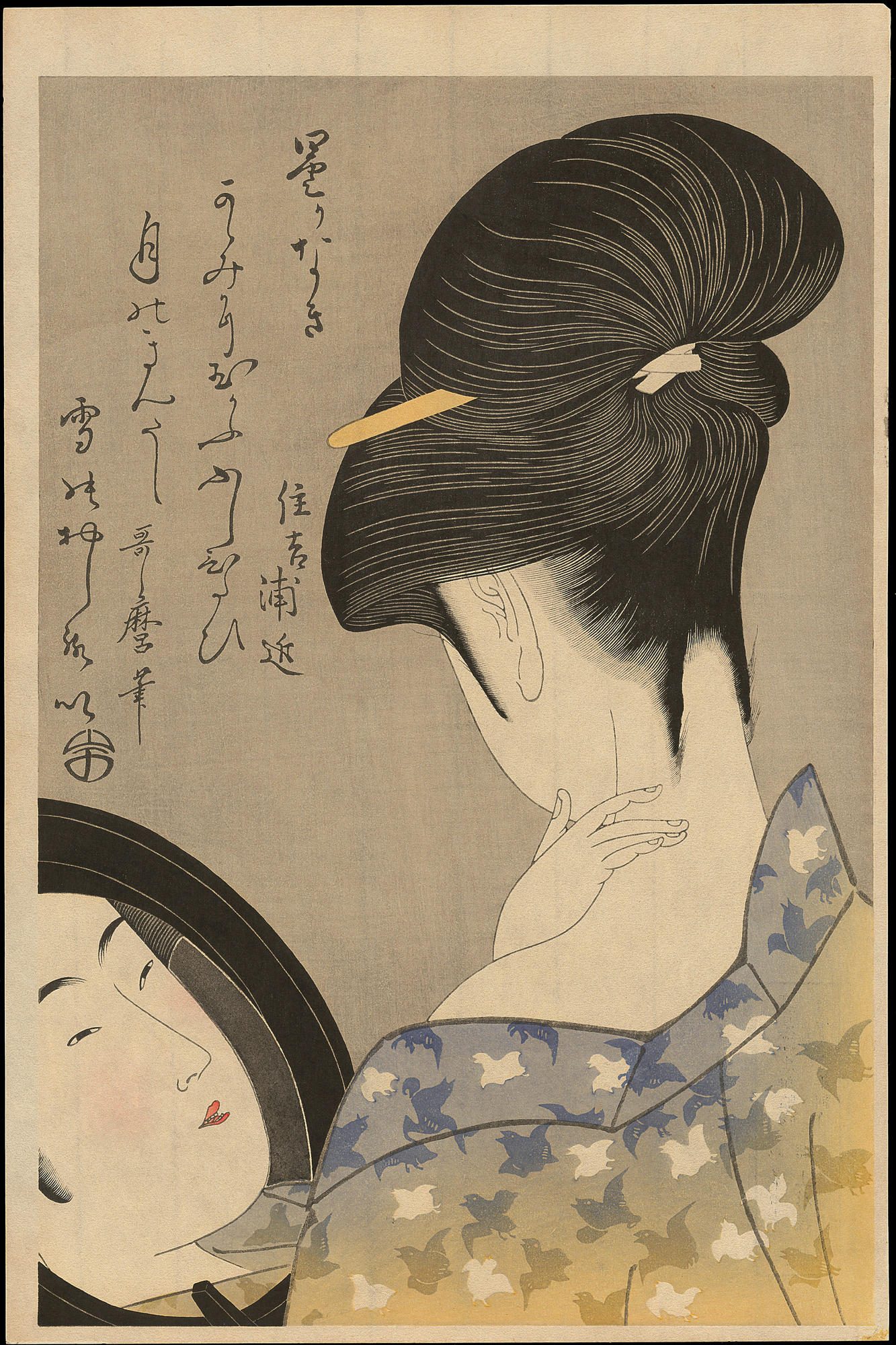

The particularity of this typically Japanese imagery does not lie in the printing process, but in the developments offered by Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725-1770), inventor of the Nishiki-e, the brocade picture, that is to say the polychrome print using as many matrices as the colors used.

But the Japanese, better perfectionists than inventors, made the technique virtuoso by combining overprints but also by developing split-fountain inking (the application in one pass of several molten colors in gradation). Some popular prints thus exist in various chromatic atmospheres specific to a print run, whether it’s the artist's fantasy or the printer's freedom.

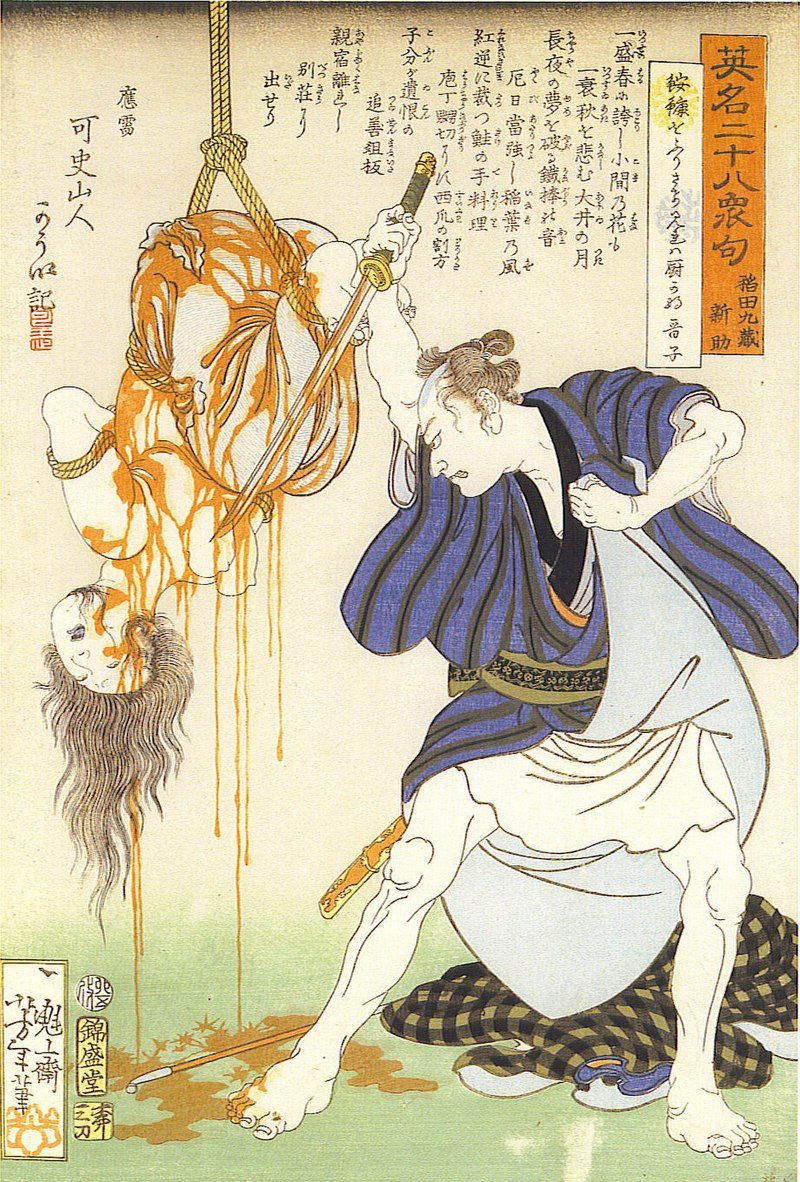

From the influence of Chinese painting, the imagery of Ukiyo-e retains only the sense of emptiness, the slight eccentric composition, the taste for landscapes and the calligraphic brush stroke. The contributions of the engraving technique will more durably impose an aesthetic favoring the cutting of planes by colored flat tints, a restricted and studied chromatic palette. However, within the constraints, artists developed daring points of view and a taste for popular scenes: feminine beauty (bijin-ga), scenes from Kabuki theater and literature, erotic prints (shunga), torture scenes (muzan-e). When the high social classes bought paintings, it was the popular and urban classes who acquired prints, reflecting a Japan of the people for the people.

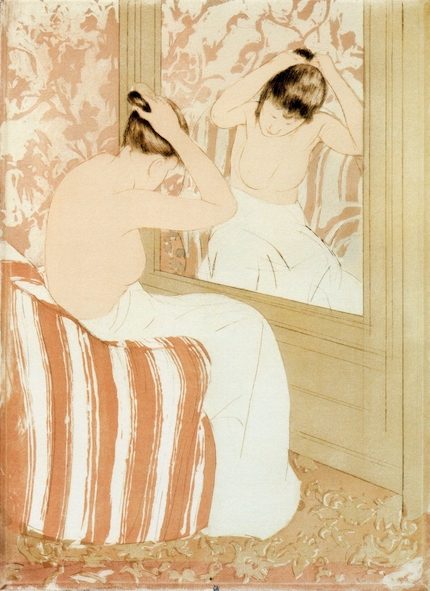

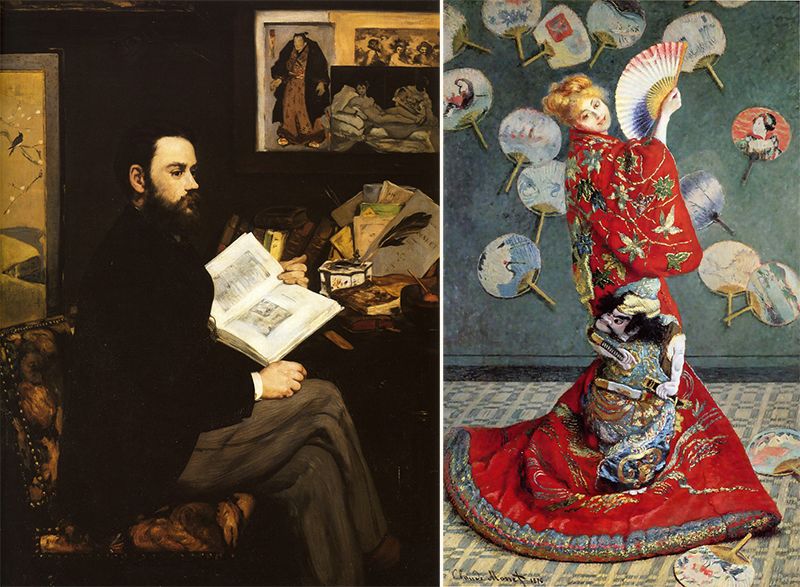

Marriage: reciprocal influences

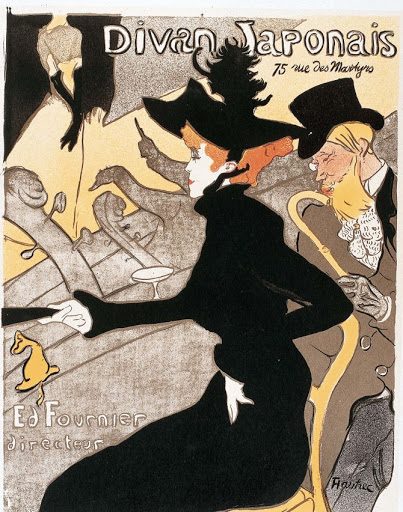

In 1852, Japan opened up to the world once again, initially accepting commercial exchanges with the United States. Trade between the West and Japan was reciprocal: Japanese prints, already known in Rembrandt's Holland, arrived in the Paris of the Impressionists and Toulouse-Lautrec. It is the purity, the graphic versus the pictorial, the empty spaces and the colored flat tints that most influence the avant-garde of the late nineteenth century. Japonism became a Western style establishing bridges between the West and Japan and going beyond the pictorial environment to invade all forms of applied arts: architecture, ceramics, fashion and textiles, decoration, calligraphy and typography, etc.

The opening of the borders returned feudal Japan to a backward culture, and Emperor Matsuhito carried out a vast set of political reforms causing a cultural revolution accentuated by the rise of international trade and industrialization. In a few decades, the country went from a nation based on tradition and honor to a modern and capitalist state.

Graphically, the popular print loses its vivacity and the style becomes more realistic with the contact of the West. Western painting redefined what the country tolerated as a practice of its time, and even if Japanese printmaking endured, it struggled to reinvent itself in the tradition.

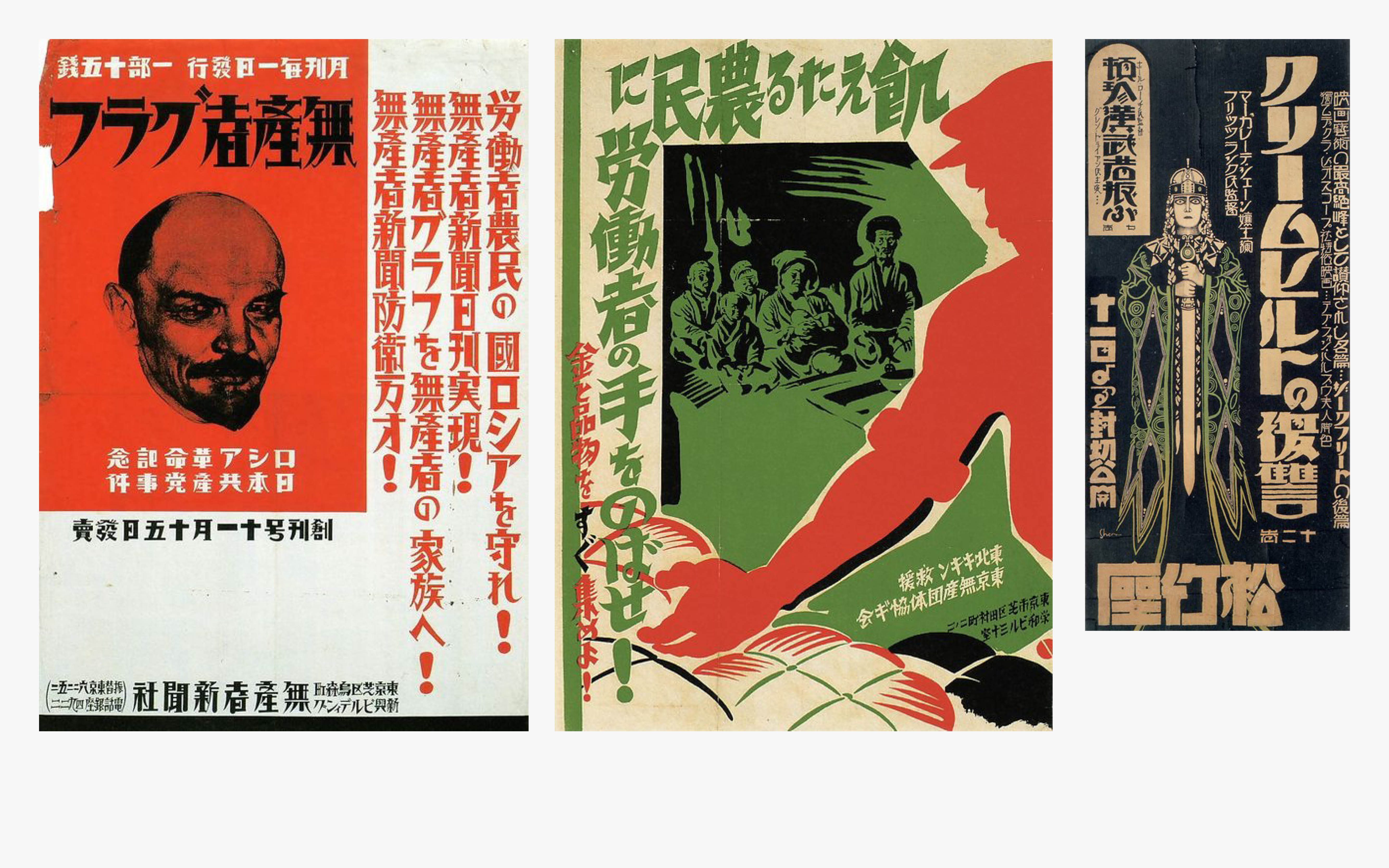

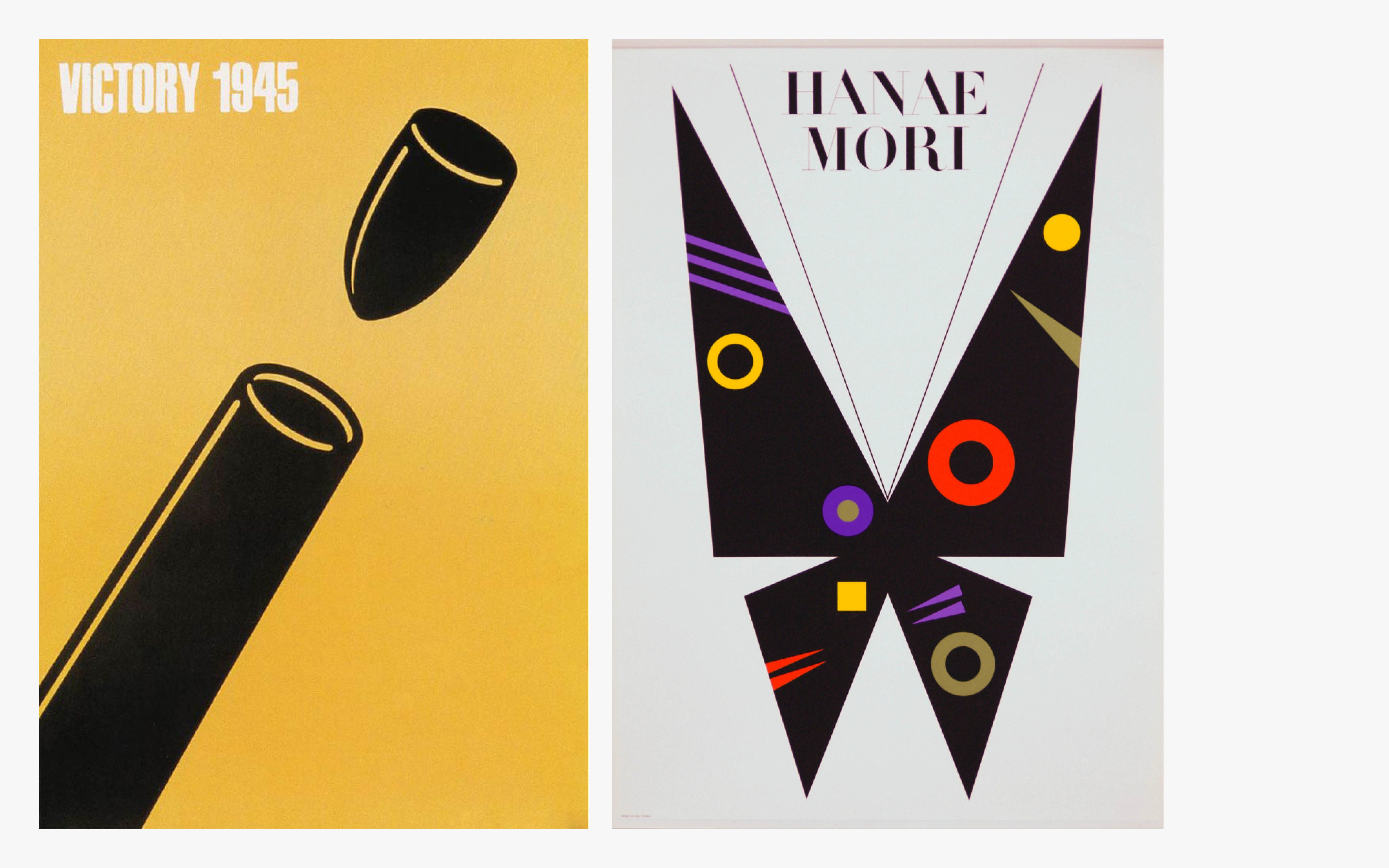

First and second modernism

Like the West, Japanese graphic design slowly took shape around the beginning of the 20th century. Defined under the various terms of dezain or shogyo bijutsu (commercial art), it operates a set of polymorphous reappropriation: advertising is inspired by European Art Deco, with its female figures with long silhouettes, as much as to a communist aesthetic, especially in the posters of political propaganda while the country tilts in an imperialist totalitarianism from the invasion of China in 1937. Paradoxically, the political aspect is close to the Chinese style: communist imagery, simplistic chromatic games, geometric formalism, even the lettering of Japanese ideograms resonate in the same way as those of the Chinese opponent.

Of course, there are nuances to this quickly painted portrait, and the figure of Gihachiro Okayama (1907-1981) could be included both for the richness of his production but also for his contribution to Japanese printmaking, marrying it with a style of woodcut influenced by German expressionism, and also as the founder of the Tokyo Advertisement Art Association.

Japan plunged into a dark period between 1937 with the invasion of China and the end of the Second World War, even in September 1952 after the departure of the American occupiers. It takes time for graphic designers to rebuild the graphic landscape of the country.

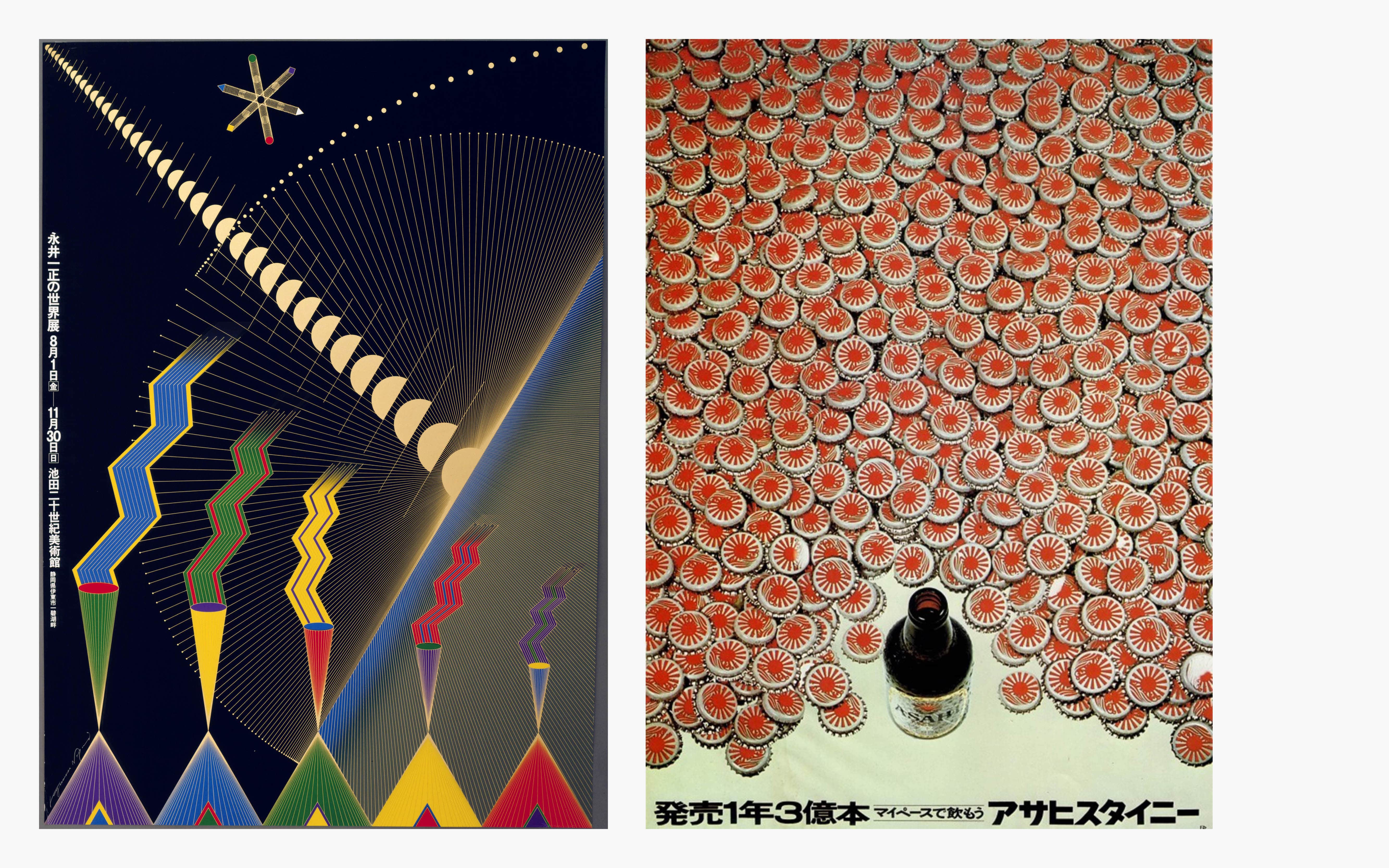

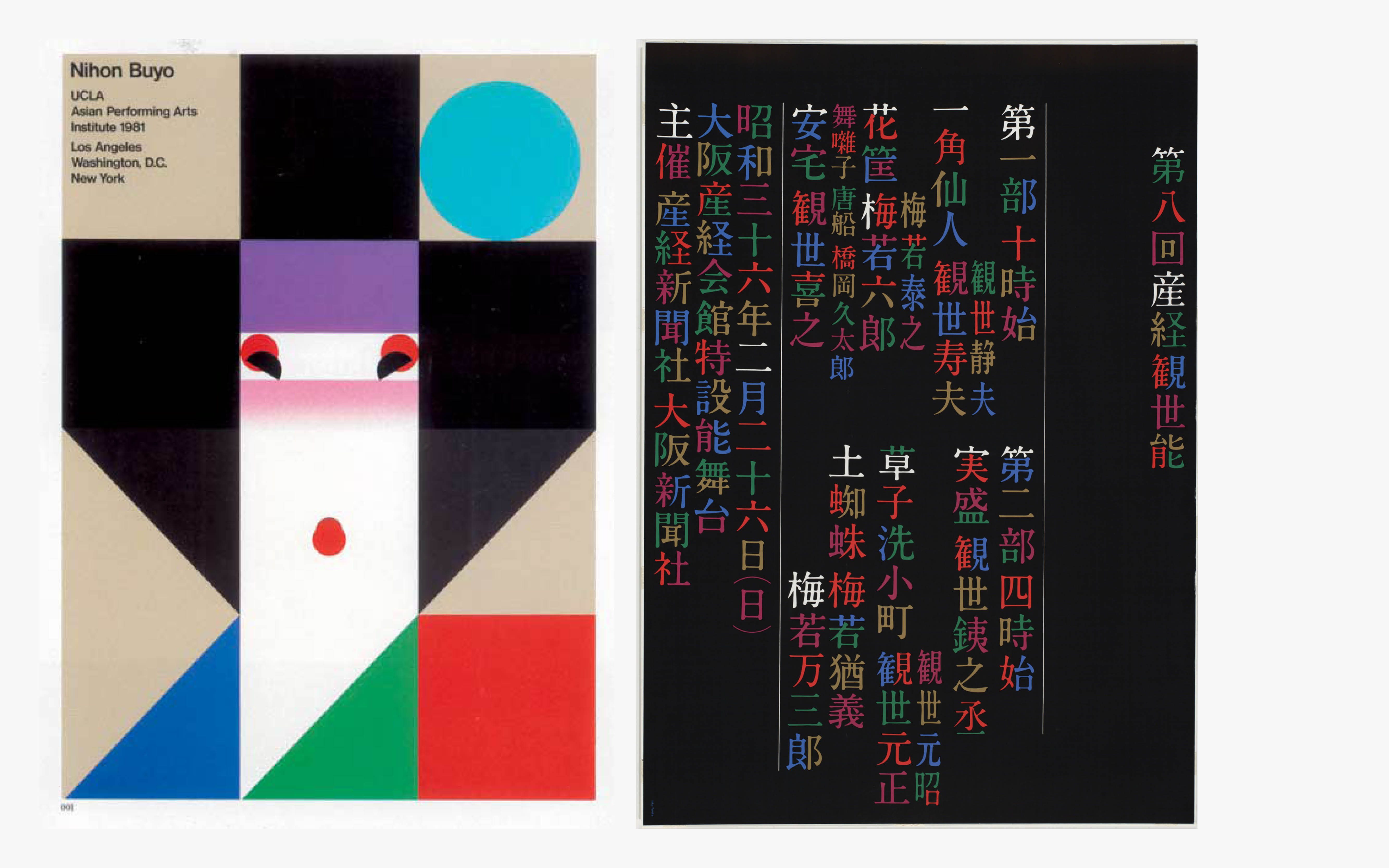

The tutelary figure of this second modernism is Yusaku Kamekura (1915-1997), a friend of the Bauhaus master Herbert Bayer but also of the American modernist Paul Rand, Kamekura digested the learnings of the West without denying his traditional Japanese culture. His posters, purely graphic or photographic, push the composition into a radical abstraction where movement is expressed with a contemporary and balanced lyricism. To confirm this, you should also look at the sense of balance, purity and elegance of the sensei's logotypes, where the influence of the kamon, the Japanese family emblems, is obvious. Kamekura, called “Boss” by his peers, is also a key player in the development of the profession through the creation of the Japan Advertising Arts Club, then the magazine Creation (1989-1994, 20 issues).

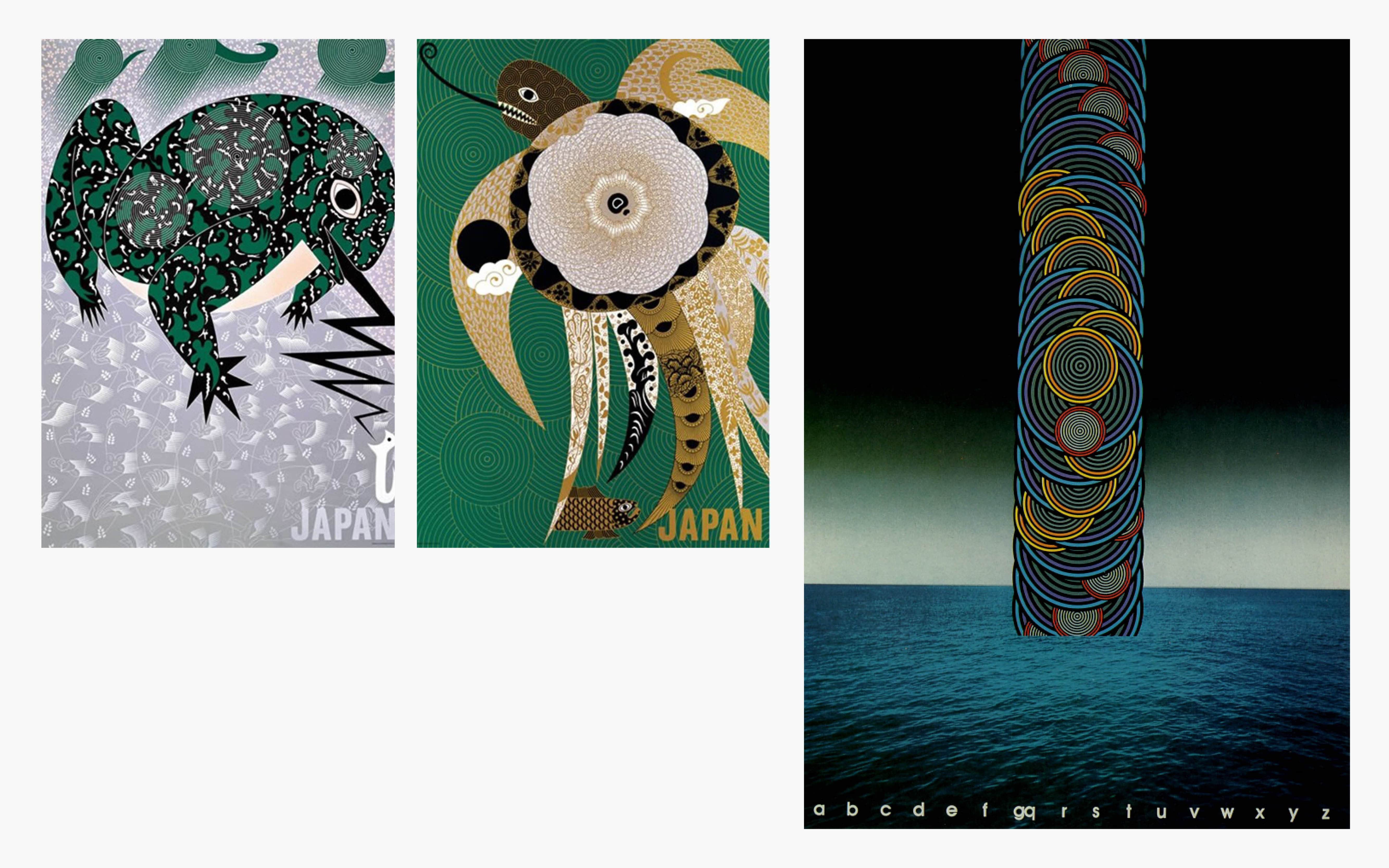

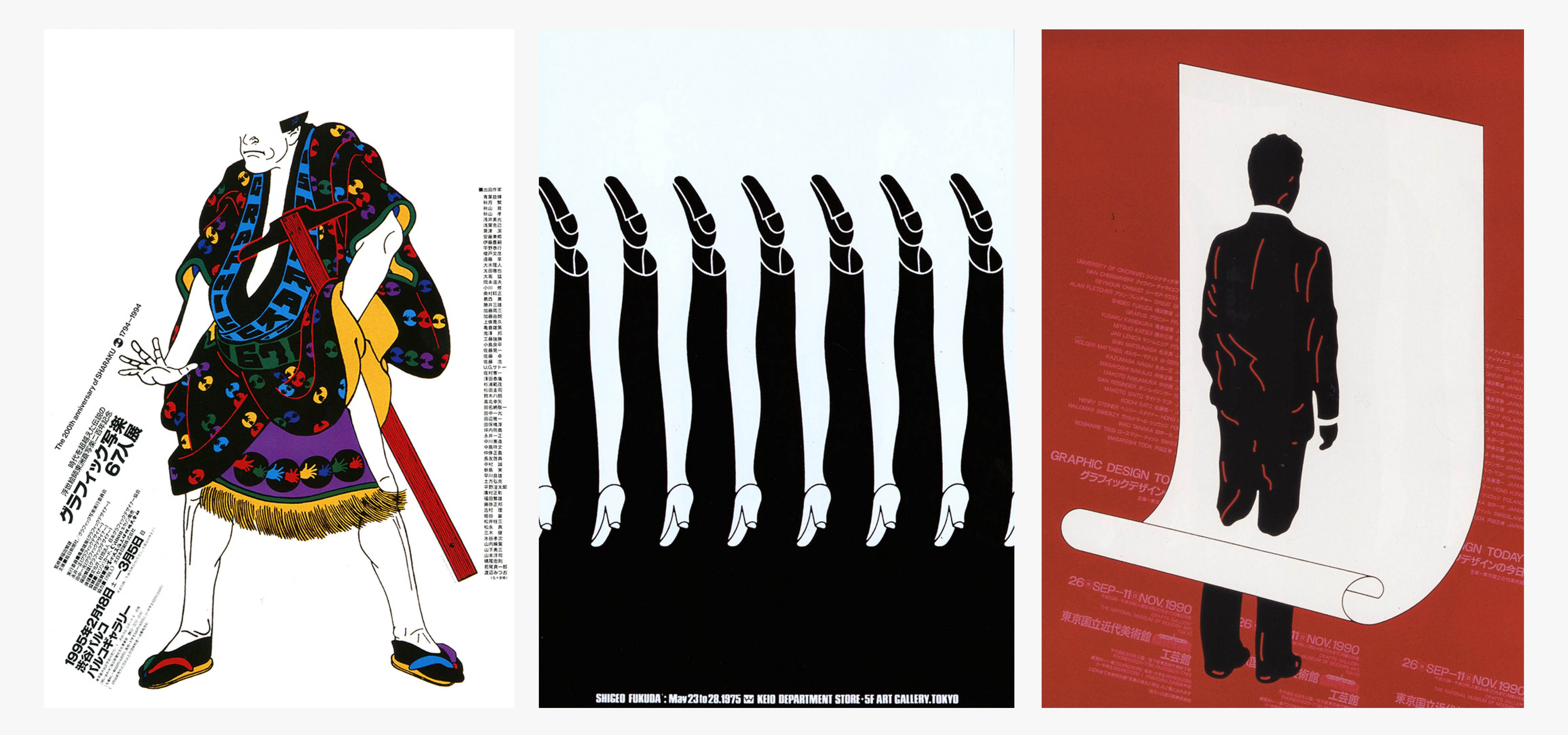

Other fascinating figures are Kazumasa Nagai (1929-), Ikko Tanaka (1930-2002) or Shigeo Fukuda (1932-2009), all of them perfect modernists tinting their productions with a clever balance between Japanese and Western influences.

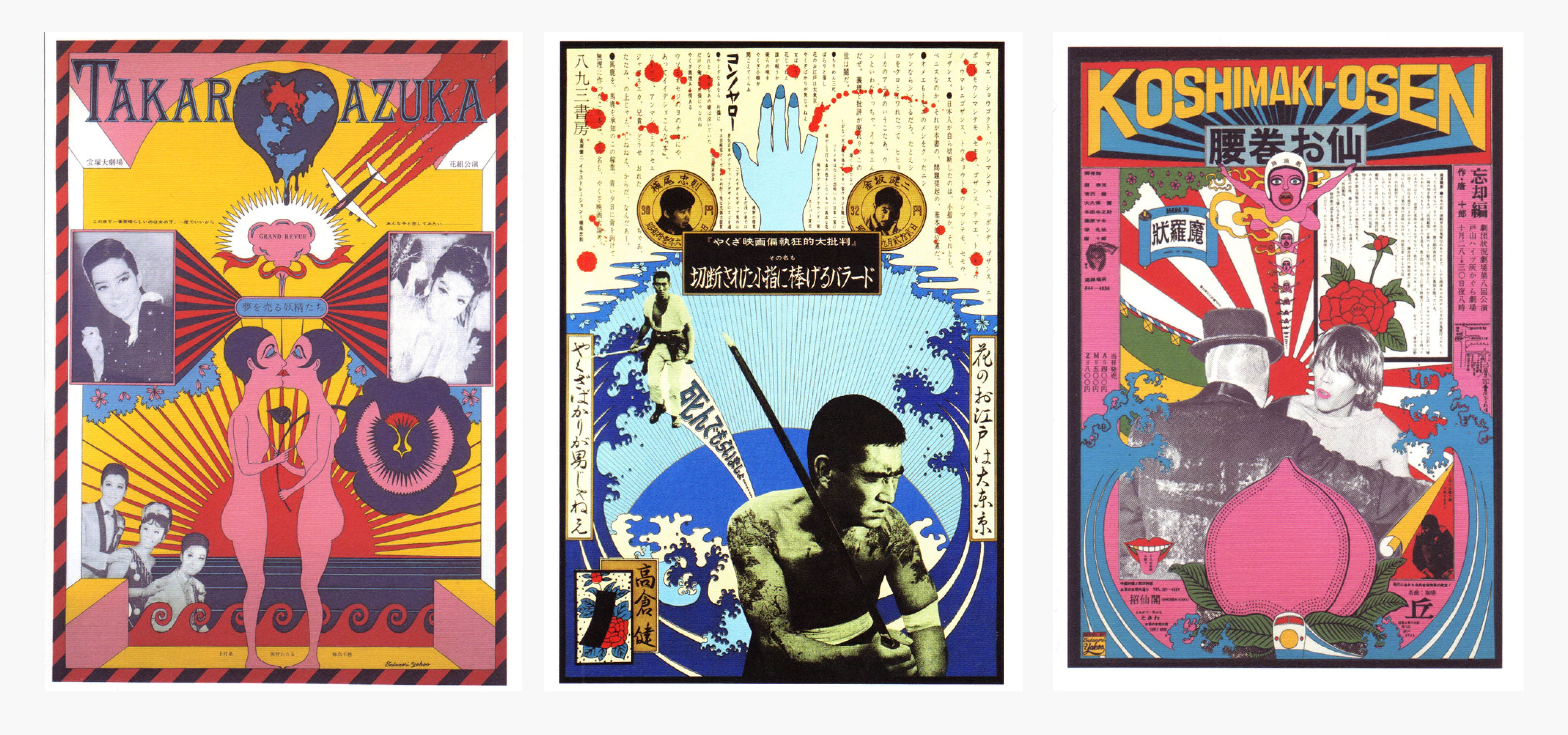

It is perhaps Tadanori Yokoo (1936-) who paradoxically remains the most Japanese of the modernists: with his radical and psychedelic style, he reinvents Japanese graphic design while extending it with a contemporary and avant-garde aura. Seen through Western eyes, he could be a Western and Japanese graphic designer using Ukiyo-e imagery with a Pop-Art palette but with the exuberance of San Francisco psychedelic silk screened posters.

However, he is deeply rooted in the national tradition, his sense of purity but also the sense of contrasting colors specific to the kimono as well as to popular festivals. For Japan is also a country of excess, where humor is both absurd and vulgar, where the elegance of the sacred cross the path of theprofane’s scatophilia, where everything is seen through the prism of respect for tradition, values and the law. By its audacity and its capacity to marry opposites, Japanese posters still remain for Western graphic designers a virgin land which, although invaded and tainted by Western culture, never ceases to reinvent itself in a natural purity.

Learn more:

Modern Graphic Design in Japan: great source for the pre modernist era.

A japanese graphic design history timeline

Gurafiku: a tumblr devoted to Japanese posters.

Here's aninterview of its creator, Ryan Hageman.

Japanese publications with english texts

Idea (1945-): still in activity, nearly 400 issues.

Graphic design (1956-1989): japanese graphic design magazine, 100 issues, edited by Masaru Katsumi (1909-1983).

Creation (1989-1992): 20 issues, edited by Yusaku Kamekura (1915-1997)

Graphis #138-139, 1968, Special Japan issue: double issue featuring the best graphic design from Japan.

About the author

Sébastien Hayez was an art director and graphic designer before becoming an art teacher and an independent researcher in the field of graphic design and type design history. His main topics are the history of logos, square books, modernism, and the minimalist italian designer AG Fronzoni 1923-2002. You can read his contributions in the pages of magazines such as Etapes, TheShelf Journal, Pli, Kiblind, Yellow Submarine, Fiction, or listen to his lectures for Les Rencontres de Lure or Fonts & faces #7.