By Sebastien Hayez. Published May 13, 2025

Stencil: an avoided history | 2/2

Typographic paradoxes

For many decades, two trades seemed to coexist without sharing much in the way of chemistry: on the one hand, decorators and engravers producing stencils, and on the other, typographic foundries accustomed to the demands of a practice dating back to the Renaissance. Blending handcrafted decoration and the science of art seems as different as the work of cut-iron and type casting.

And yet there are similarities, since industrialization made great use of decorative alphabets to adorn city-center poster walls, as well as the frontispieces of Romantic editions. From 1850 onwards, stencil lettering took on a more creative and assertive role, integrating breaks and bridges into the letter's design. Some stencil letters exploit breaks as an arbitrary rhythm, others work with ornamental effects (zebra stripes, lightning bolts, raised ribbon effects); the most developed form polychrome ornamental typography, or ornate letters inspired by Simon Fournier.

Paradoxes abound in the world of stencils.

The first paradox is that, for industrial and logistics stencilling, these letters are obtained by striking a punch on a metal plate. This punch is similar in appearance to the one needed to cast typographic characters.

The second paradox is that the appearance of a font with the appearance of a stencil seems absurd, just like simulating handwriting, or the volume effects of romantic alphabets. And yet, stencil letters have become synonymous with standardized, industrial writing.

Finally, the third paradox lies in the shape of the first Stencil typeface.

This typeface, known simply as Stencil Gothic (MacKellar, Smiths & Jordan, Philadelphia, 1885), is the work of John West, son of punch engraver and type designer James West, renowned for his script typefaces. It consists of a capital lineal, available in 3 sizes (10, 12 and 18 pts) whose bridges break the counterforms vertically. The cold, geometric appearance is counterbalanced by the plant-like ornamentation. The brilliant stroke of this first stencil typeface would remain solitary for over 45 years.

Credit.

Standardized writing for artists

The case of Auriol, published in 1902 by the Deberny & Peignot foundry, is not strictly speaking a stencil typeface, even if its design respects the constraint of bridges linking counterforms and shapes. However, George Auriol, its designer, conceived a typography inspired by the brushstrokes of Far Eastern scripts. The numerous vignettes and markings illustrated in the volumes of his works clearly show that the inspiration is a fine one: should we see in Auriol a deep understanding of Japanese motifs stenciled on popular fabrics?

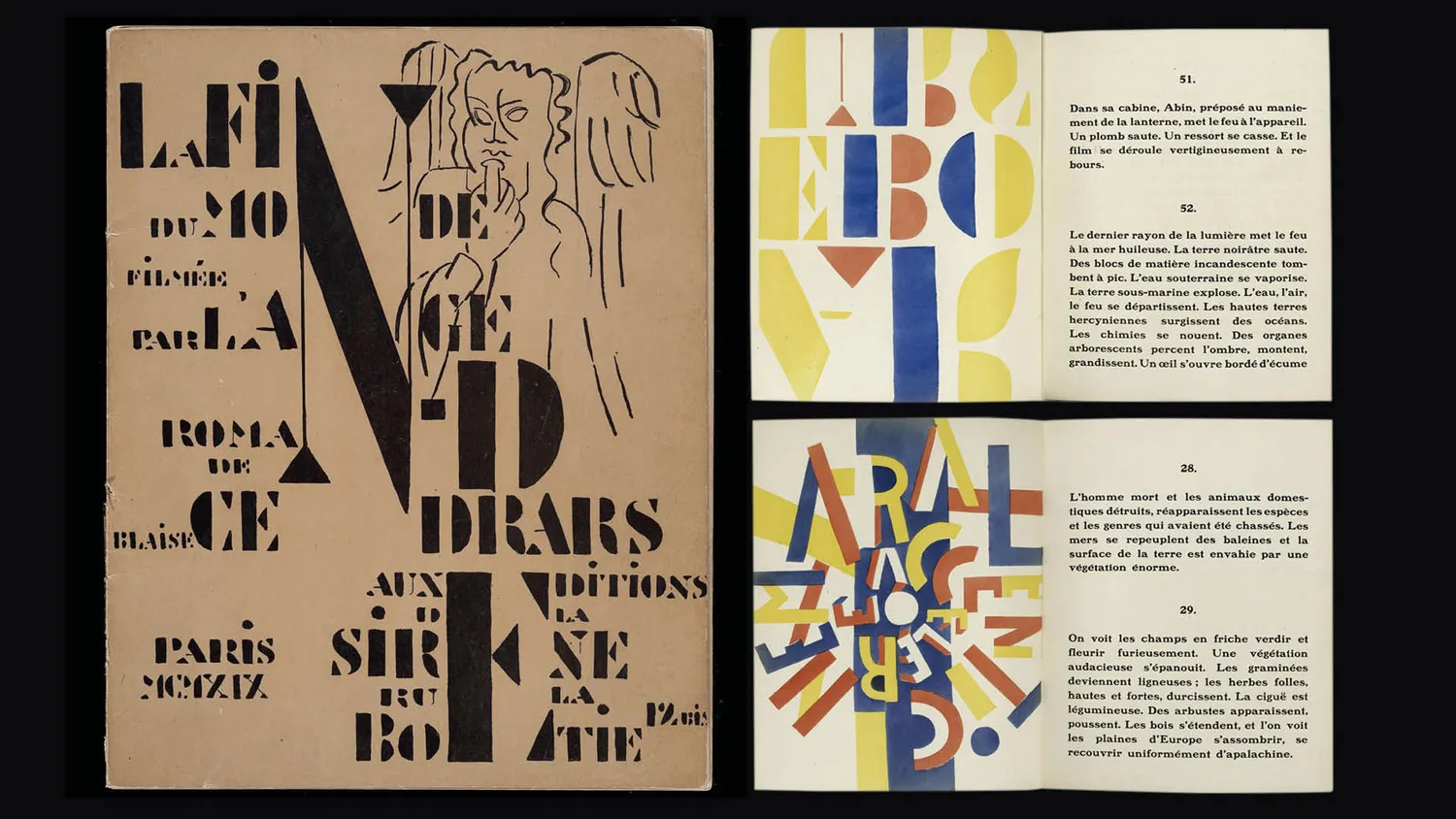

However, it wasn't until 1920 that many artists began to invest their work with lettering and, more specifically, stencils. The beginnings appeared at the turn of the century, with compositions combining painting and typography, first by the Cubists, then by the Futurists and Dadaists. So when purist artists such as Le Corbusier and Léger began using stencil typefaces in 1917, they opted for a standardized, easy-to-use tool that incorporated lettering and painting without breaking the medium. The show of force was achieved in 1919 with La Fin du monde filmée par l'ange N-D, by Blaise Cendrars and Fernand Léger, which made masterly graphic use of the elementary forms of stencils. By return of influence, painters such as the Portuguese Amadeo de Souza Cardoso incorporated these typographies into their cubist paintings. Sonia Delaunay went so far as to create Alphabet (Ecole des Loisirs, 1974), a children's alphabet book made of colorful stencils.

Le Corbusier's use of the term inspired other architects to follow suit, notably the Anglo-Saxon James Stirling and Alison and Peter Smithson. Others, such as El Lissitzky, came as constructivist artists, linking the fine and applied arts. These European stencil alphabets are mostly associated with didone models.

But the designers of the second wave of Modernism seized upon it in the post-war period. Charles & Ray Eames' use was justified by a constructive but accessible graphic style, perfectly illustrated by stencil letters in shimmering hues.

Gerd Arntz, Otto Neurath's assistant on the development of ISOTYPE, uses stencil typefaces for their industrial connotations as well as their impersonal, standardized look. But this was hardly creative in the light of what the avant-garde were venturing to develop alongside these uses.

The composite writing of the avant-garde

The influence of traditional stencils is probably not to be found in Asia, but rather in Russia. In 1918, the Russian Telegraphic Agency (ROSTA) was set up to communicate political and public health messages to the public in the form of posters displayed in shop windows. Before being printed in lithography, these "Rosta windows" were reproduced using mixed techniques: linocut for the images and stencil for the text. Given these technical constraints, the artists drew their inspiration from popular Soviet imagery, limiting chromatic effects to vivid, striking flat tints. In the same way, the lettering gains in expressiveness from the breaks and bridges made on vigorously traced stencil letters.

2. Credits

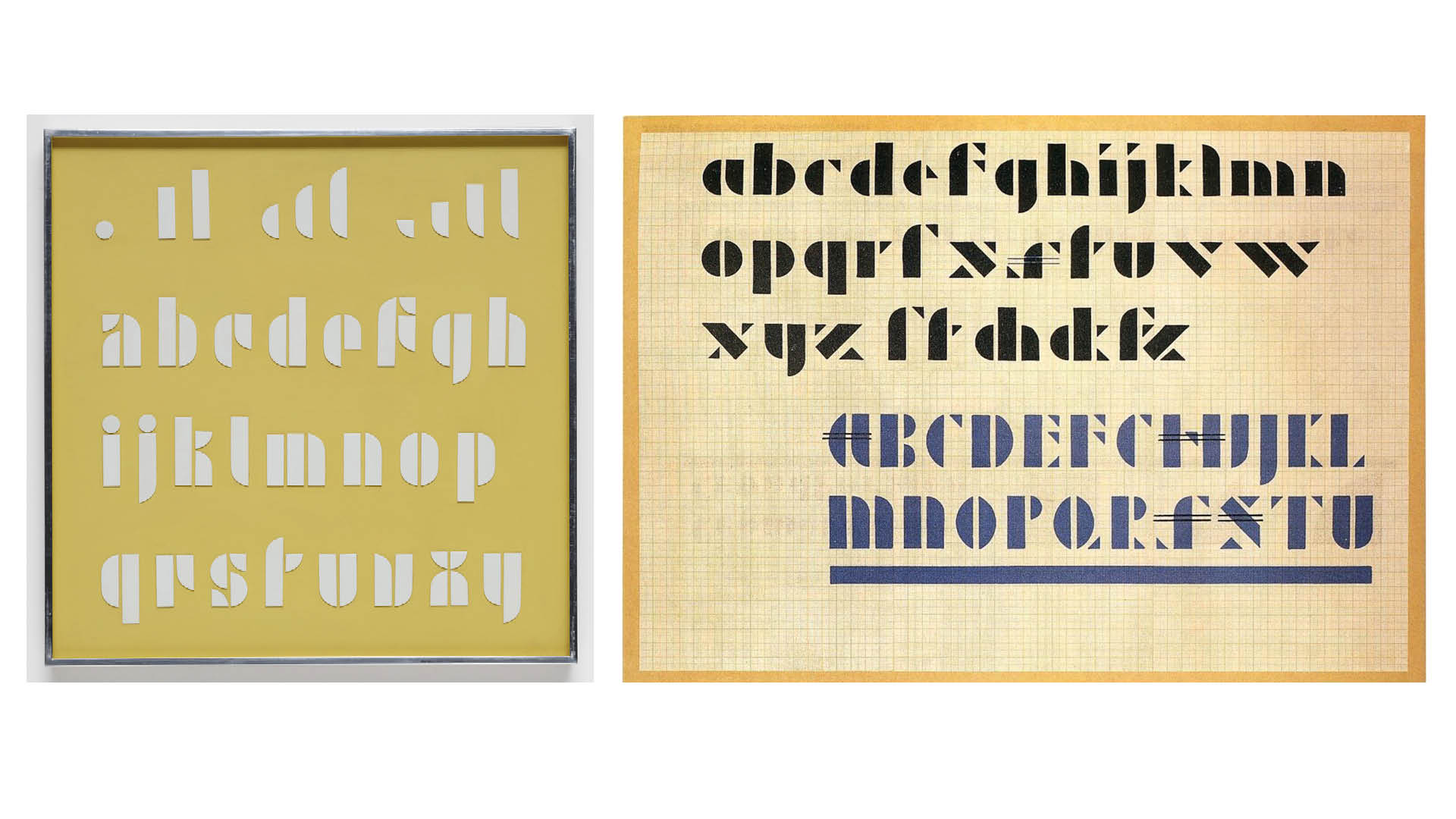

At the crossroads of Le Corbusier and the Constructivists, there are two poles: Neoplasticism and the Bauhaus. There are few examples of the former, apart from the logo of the magazine de Stijl (Vilmos Huszàr, 1917), whose horizontal and vertical rectangles spare space for the stencil-printable alphabet, and a few stencil writings integrated into the paintings of certain artists. As for the Bauhaus, its students explored an elementary formal grammar: circles, squares and triangles were enhanced by primary colors. In the mid-1920s, Josef Albers experimented with geometric alphabets composed of interlocking geometric modules, giving rise to the Schablonenschrift (stencil font, 1926) and shortly afterwards the Kombinationschrift (combined font, 1929). The modular aspect of this typeface found its raison d'être in its privileged use in architecture, allowing builders to incorporate letters into concrete by assembling modules.

2. Original Josef Albers designs from the Bauhaus Archiv. This image was found on the internet with no accompanying information; if you are the copyright holder and wish it to be removed, we will be happy to do so. Credits.

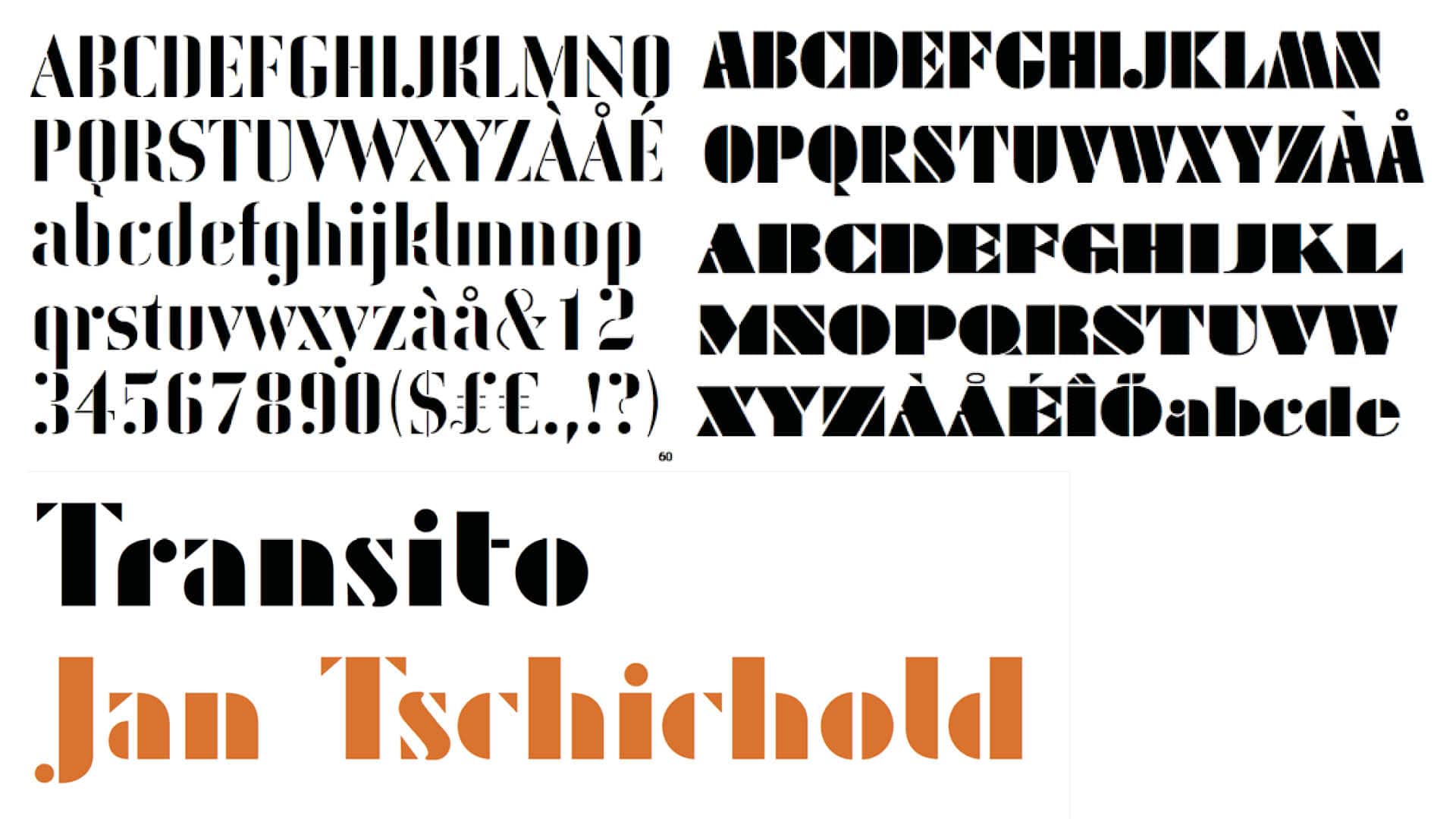

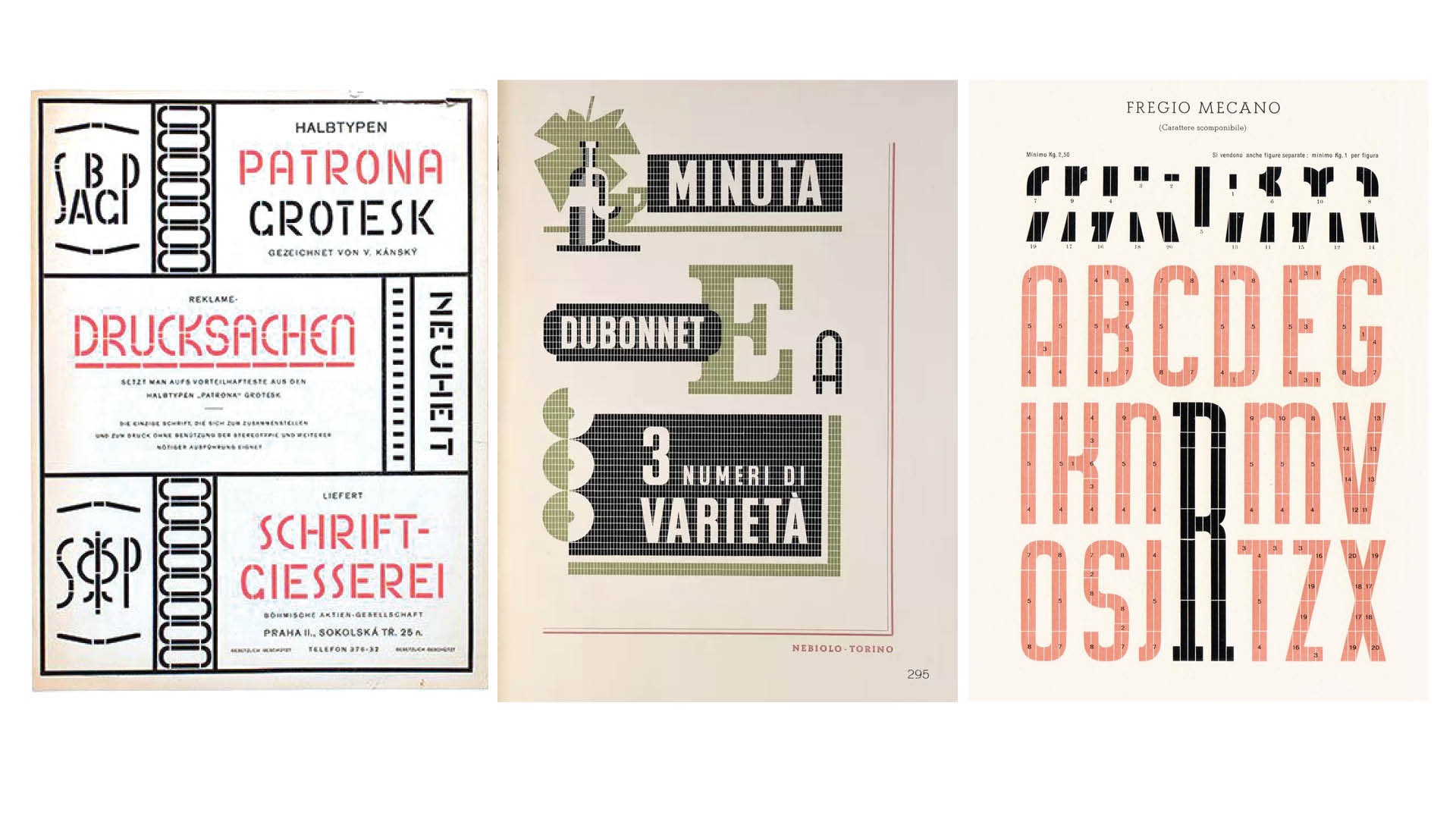

His fellow Bauhaus masters, Joost Schmidt and Herbert Bayer, adopted a similar approach, which in turn inspired other graphic designers such as Jan Tschichold and his Iwan Stencil (1929) and Transito (1931), or Paul Renner who extended his Futura with a Black font (1929) with Art Deco stencil accents, followed by typefaces such as Braggadocio (W. A. Wooley, Monotype, 1930), Schablone (Otto Weisert Typefoundry, 1931). Less popular was the Patrona Grotesk (V. Kànský, Slevarna Pisem, 1931), a set of 38 geometric modules enabling the composition of Latin and Cyrillic characters of different heights. Shortly afterward, the Fregio Mecano (Giulio da Milano, Nebiolo, 1933) followed suit with 20 modules, then the Fregio Razionale (Giulio da Milano, Nebiolo, 1935), again with a modular typeface, but in negative.

The predecessors of these constructive letters can be found if we go back to the mid-19th century, when the USA manufactured stencil letters using simple punches perforating metal. Reduced to simple, quasi-modular shapes, the result was not far off the Futura Black that appeared several decades later.

1. Patrona Grotesk 2. Fregio Mecano 3. Fregio Razionale

Industrial writing

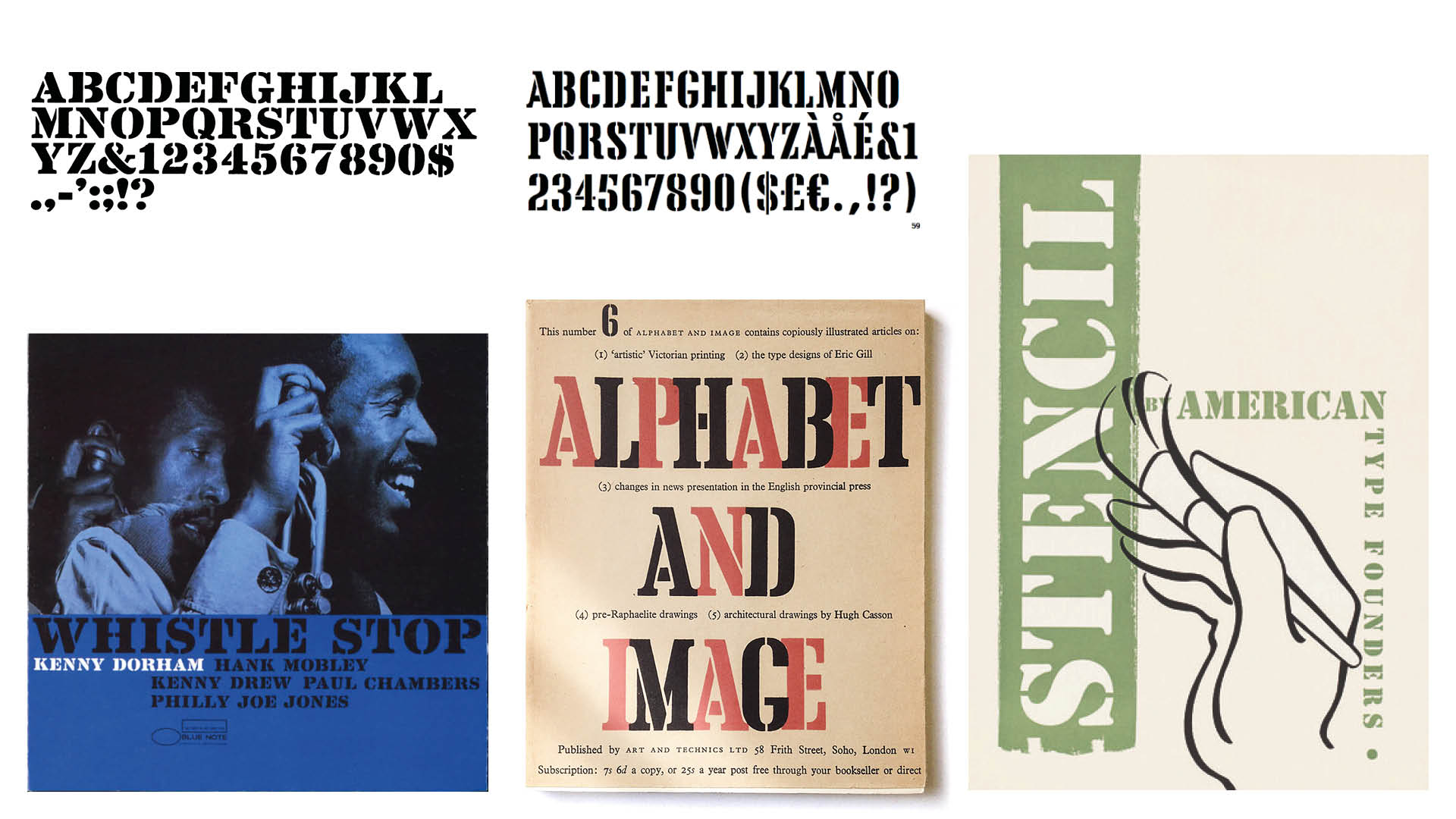

Although the 1920s and 1930s featured typefaces with a constitution compatible with stencils, none of them strictly featured stencils applied in everyday life. It wasn't until 1937 that two American foundries simultaneously distributed two Stencil types, by Ludlow Typography (Robert Hunter Middleton) and American Type Founders (Gerry Powell). The first is a Clarendon with a generous width; the second is very similar, but tighter and with slightly longer serifs. For the public, these two typefaces remain those used on military equipment during the Second World War.

Two years later, it was the turn of Tea-Chest (Robert Harling, Stephenson Blake, 1939) to present a stencil inspired by a condensed Clarendon, but with reduced serifs and more assertive breaks. As its name suggests, this typeface was inspired by the stencil letters found on the wooden crates used to transport tea. The three interwar typefaces are available in capitals only, in the image of their historical models.

Thereafter, several case studies can be observed.

The first was the development of stencil typography inspired by 19th-century practices. In the early 1950s, Marcel Jacno began a fruitful collaboration with the Théâtre National Populaire (TNP) troupe housed at the Théâtre de Chaillot in Paris. The logo features the acronym in an oval, stencilled in a strikingly popular style. For the text on his posters, Jacno still favors stencils inspired by the Didots of the last century. Given the success of his communication, the typefaces were offered to Deberny & Peignot in 1953 in the form of transfer letters, similar to the Letraset typefaces just marketed in the USA. Jacno's work took on a new dimension, however, with the development of a complete typeface. The capitals are Fat Faces (Normandes) with significant breaks; the lower-case letters have no serifs and are slightly slender, reminiscent of a condensed grotesk. Above all, the outline is not the clean line of the stencils, but the frustrated, naive application of the final rendering.

In short, he was the precursor of the grunge typefaces that were to have their heyday in the mid-1990s.

The second case in point is the creation of typefaces drawing on the elementary geometry of the interwar period. Super Tipo Veloz (Joan Trochut Blanchard, Iranzo, 1942), for example, is a fantasy typeface available in 3 different fonts, including a typical Art Deco typeface, Didot sans serif, rendered stencil-like by the broken lines. Baby Teeth (Milton Glaser, Photo-Lettering Inc., 1968) is a purely geometric titling typeface, inspired by Art Deco poster lettering, but deprived of its counter-forms. The letters stain the surface with massive solids, while giving geometry its most playful aspect, akin to a child's building set.

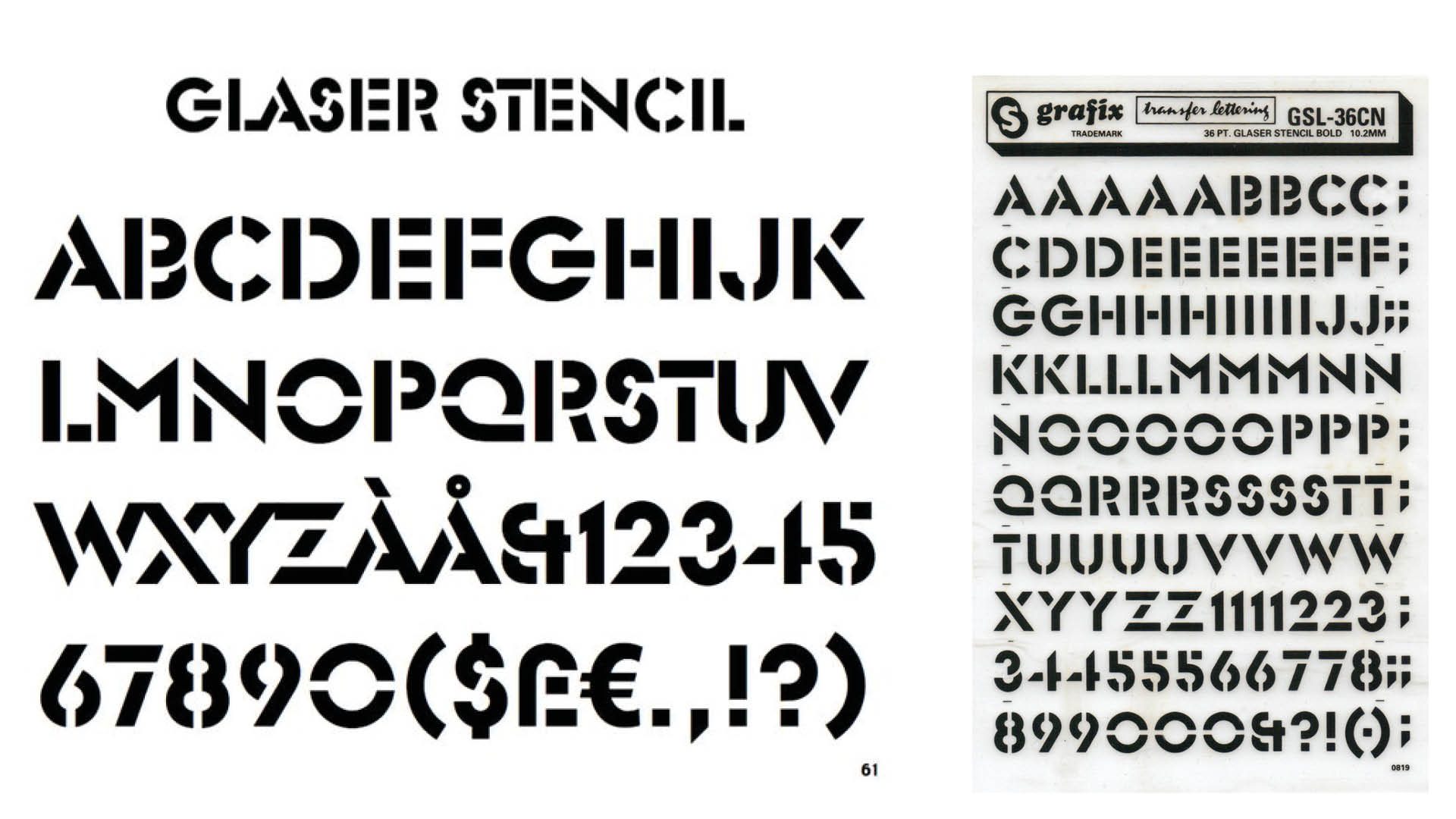

A final trend is the adaptation of contemporary typography to the constraints of stencils. Milton Glaser, again, saw stencils as a favorable creative ground, and as early as 1968, exploited a geometric linear in his personal work. The typeface came to life in 1969 at Photo-Lettering under the name Glaser Futura Stencil, before being renamed Glaser Stencil in 1970. Available in three weights, it has no lowercase.

The other great stencil artist is Frenchman Philippe Apeloig, whose typographic creations are in the tradition of both the geometric lettering of De Stijl and the designs of Dutchman Wim Crouwel, Apeloig having cut his teeth at Total Design in the Netherlands. Aleph (1994), Octobre (1994), Poudre (2008), Coupé (except O, 2011), Abf (2010), Ndebele (2010), Izocel (2011), Ali (2012).

That letters can teach us a great deal about the evolution of techniques is nothing new. What the stencil letters teach us is how, through a rudimentary technical process and unfailing ingenuity, a technical constraint can redefine our aesthetic tastes and our way of seeing shapes as elements of language. Far from needing to be reproduced with a stencil, these texts, somewhere between writing and typography, are proof that our societies produce meanings from a form and a context. Stencil letters are neither artisanal nor artistic, still less military or industrial. They are the result of an inventiveness that makes it possible to reproduce a form without great means.

This article is immensely indebted to Eric Kindel's decades-long research. Short texts accompanied by lectures provide a rough but meaningful picture of the everyday use of stencil letters.

- Recollecting Stencil Letters

- Reconstitution of techniques from Billettes

- The stencilled poster in Paris in the 19th century

- Eric Kindel - Objet-type, the French Stencil Letter

- Plaque de découpe Universelle

- "Marked by time", Eye 10, Summer 2001, 48-51

- "Stencil work in America 1850-1900", baseline 38, Summer 2002, 5-12

- Histoire de l'écriture typographique, Le XVIIIe siècle, tome ½, les écritures réalisées au pochoir, Claude-Laurent François. Dir. Yves Perrousseaux, Atelier Perrousseaux éditeur, 2010, pp.48-75.

- Histoire de l'écriture typographique, Le XXe siècle, tome ½, Sociologie et renouveau d'un caractère : les pochoirs, Jacques André. Dir. Yves Perrousseaux, Atelier Perrousseaux éditeur, 2016, pp.72-87.

- Richly documented with lots of images of equipment

- Eye no. 86 vol. 22 2013

- List of historical stencil fonts by country

- Stencil, etymology and history of the image printing process

- Short article by Heller & Filli with nice examples

- Medieval stencil decoration

- https://anrt-nancy.fr/en/projets/stencilled