By Sebastien Hayez. Published November 15, 2024

Slab: crossed stories

The richness of our typographic palettes doesn't reflect a linear evolution, like a family line where ancestors give birth to obvious descendants. On the contrary, successive marriages, adoptions and illegitimate children upset the family tree. Typography can be seen as a reflection of one's generation, itself a generator of creations. Indeed, the Vox-Atyi classification can be read first and foremost as an organization of the formal evolution of typefaces: humanist, garalde, transitionnal and didones depend on cultural and historical evolutions; mecanistic (slab) and sans reflect an extreme and internationally widespread morphology; finally, glyphic, script, graphic and blackletter encompass typefaces inspired by the written word. Having quickly traced the history of sans serif typedesign, and to celebrate the recent release of Rules Slab & Intermedial Slab, it seems only natural to tackle the history of Slab.

Fat Faces & Antiques: weighting the didone

Defined by rectangular serifs, slab or mechanics typefaces refer to a variety of typefaces not sharing the same stylistic details. Some have drop endings terminals, others a fixed width, so many clues to warrant investigation.

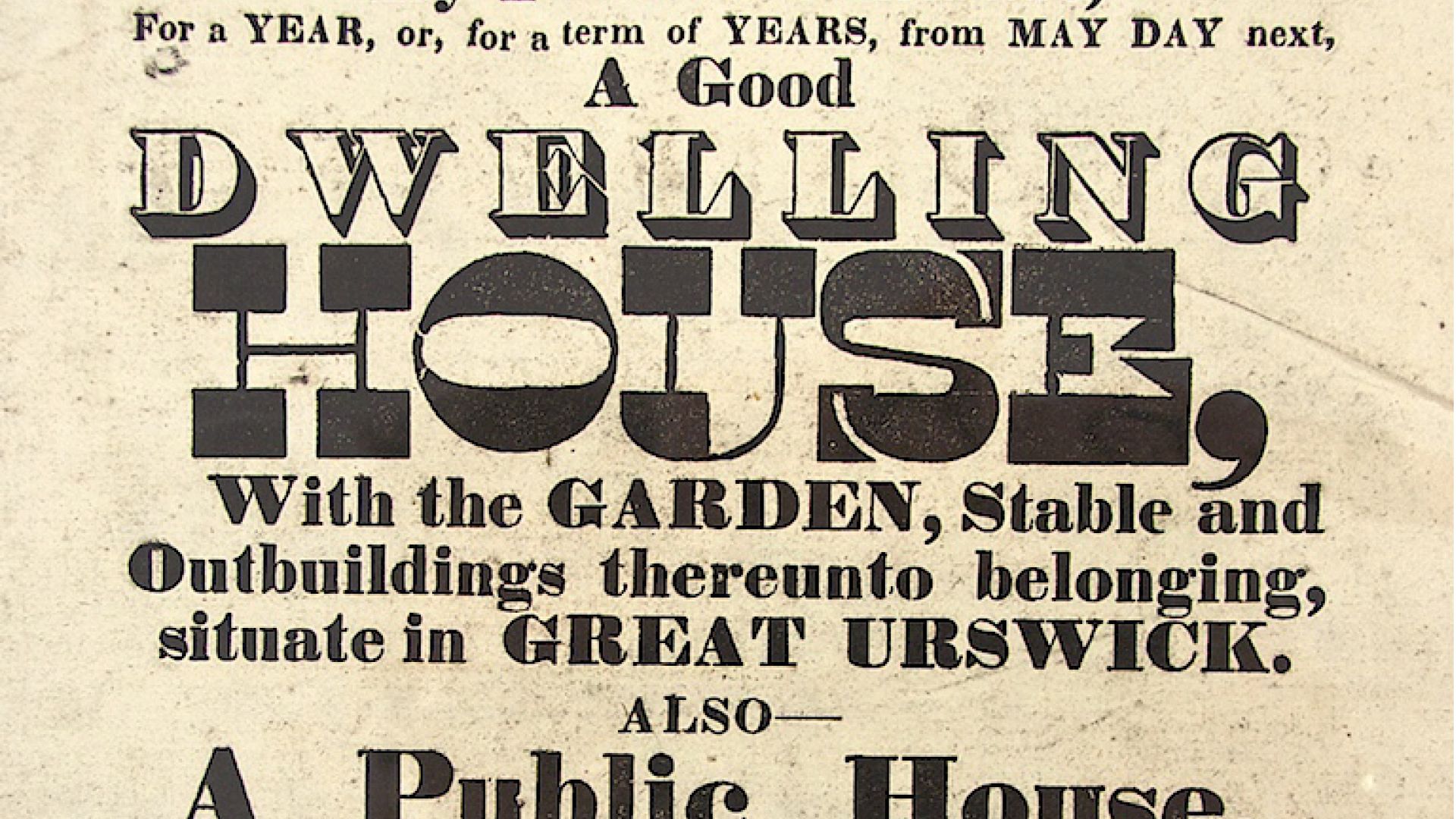

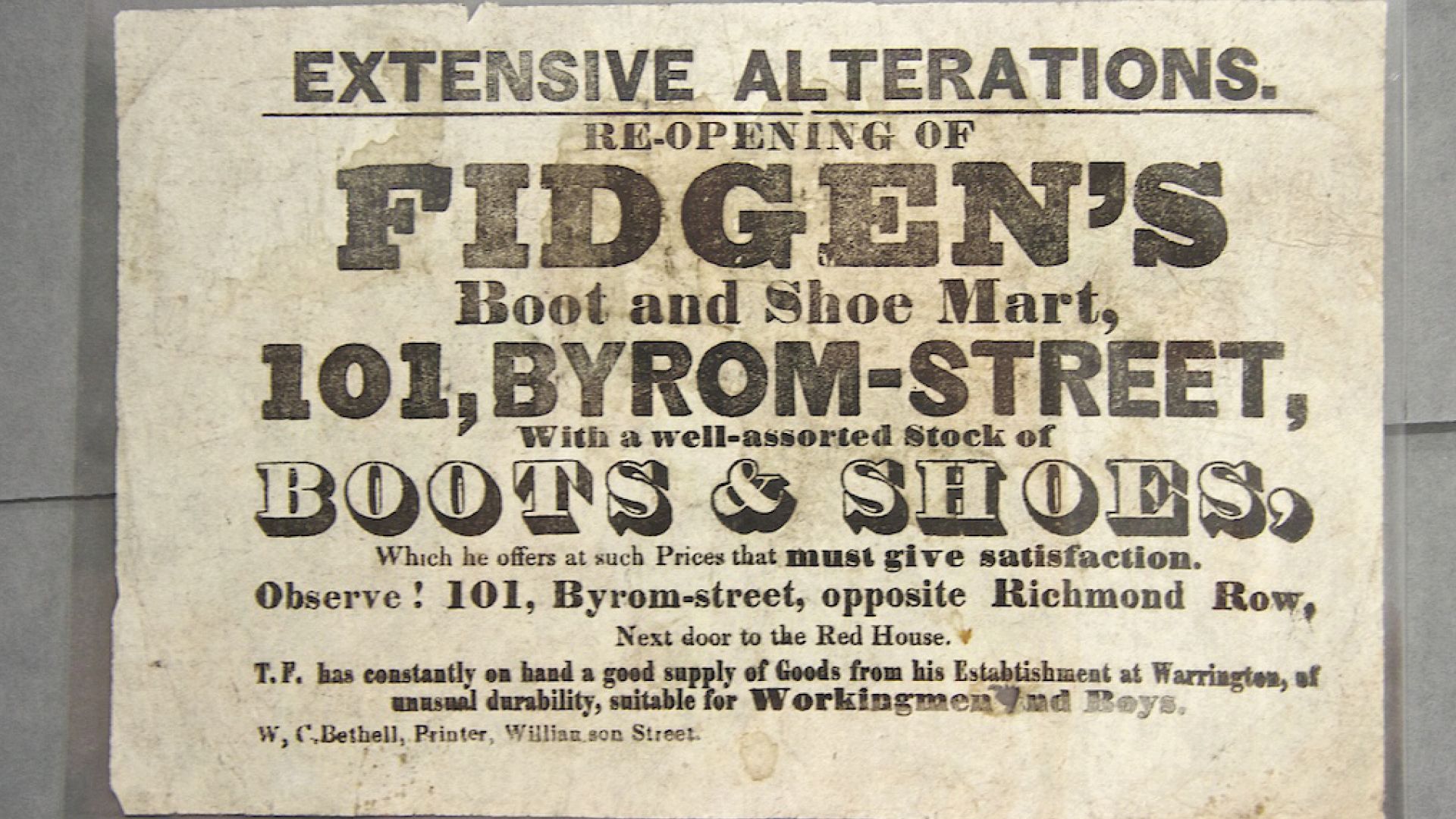

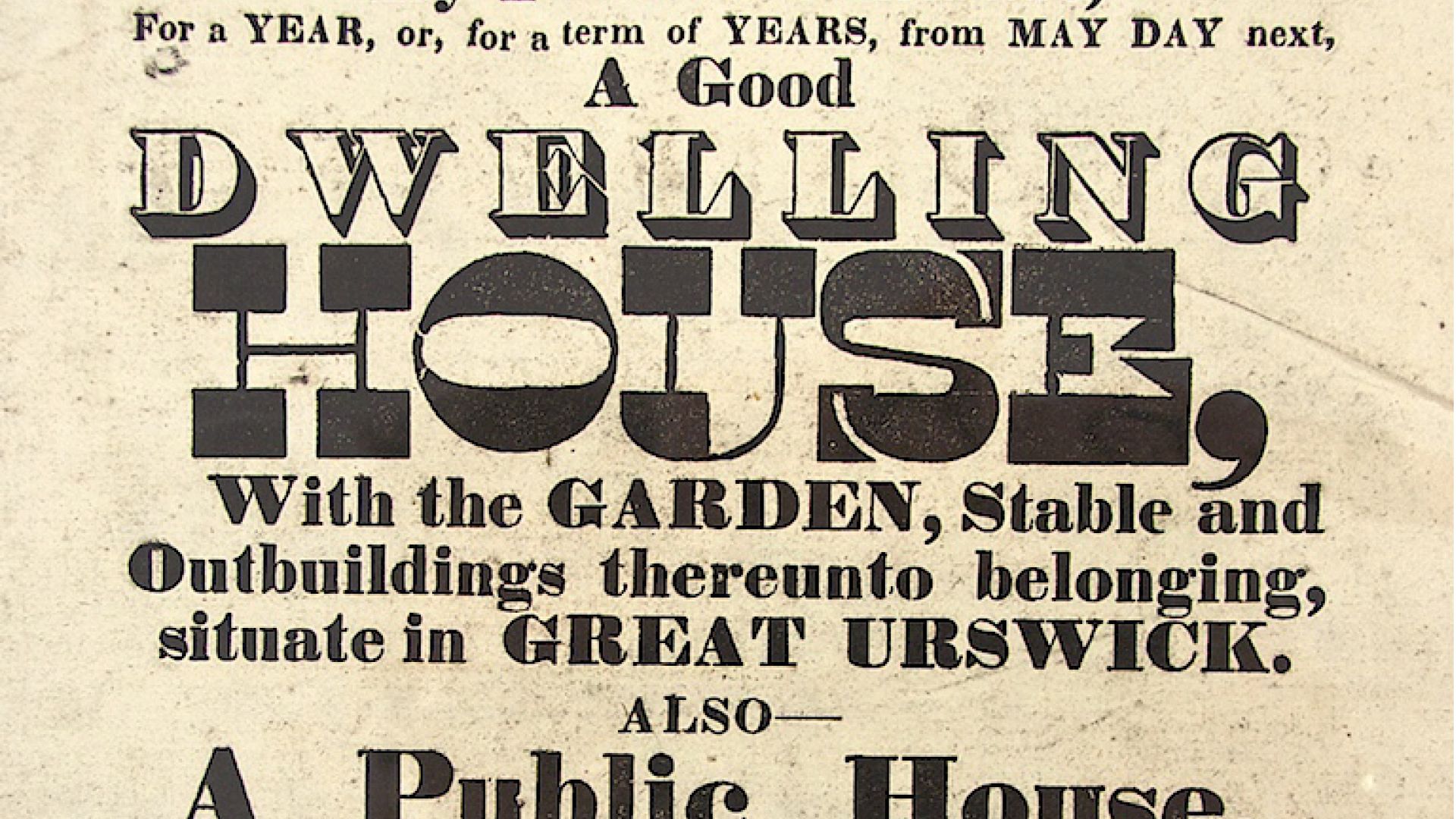

In England at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries, the Industrial Revolution blurred the boundaries of the past. Mechanical production became automated, enabling the mass production of objects. The sale of this production went hand-in-hand with the industrialization of printing from 1814, via the invention of the first steam press by Friedrich Koenig (1774-1833). While large-scale production became easier, the promotion of these products also became possible thanks to commercial posters. From the beginning of the 19th century, posters appeared en masse on the walls of London and Paris, before invading the world's major capitals. Previously reserved for official announcements, the modern poster could not exploit the old typefaces, designed primarily for publishing. The poster seeks surprise, and typographic characters are more to be seen than read.

(Source: Michael Hochleitner)

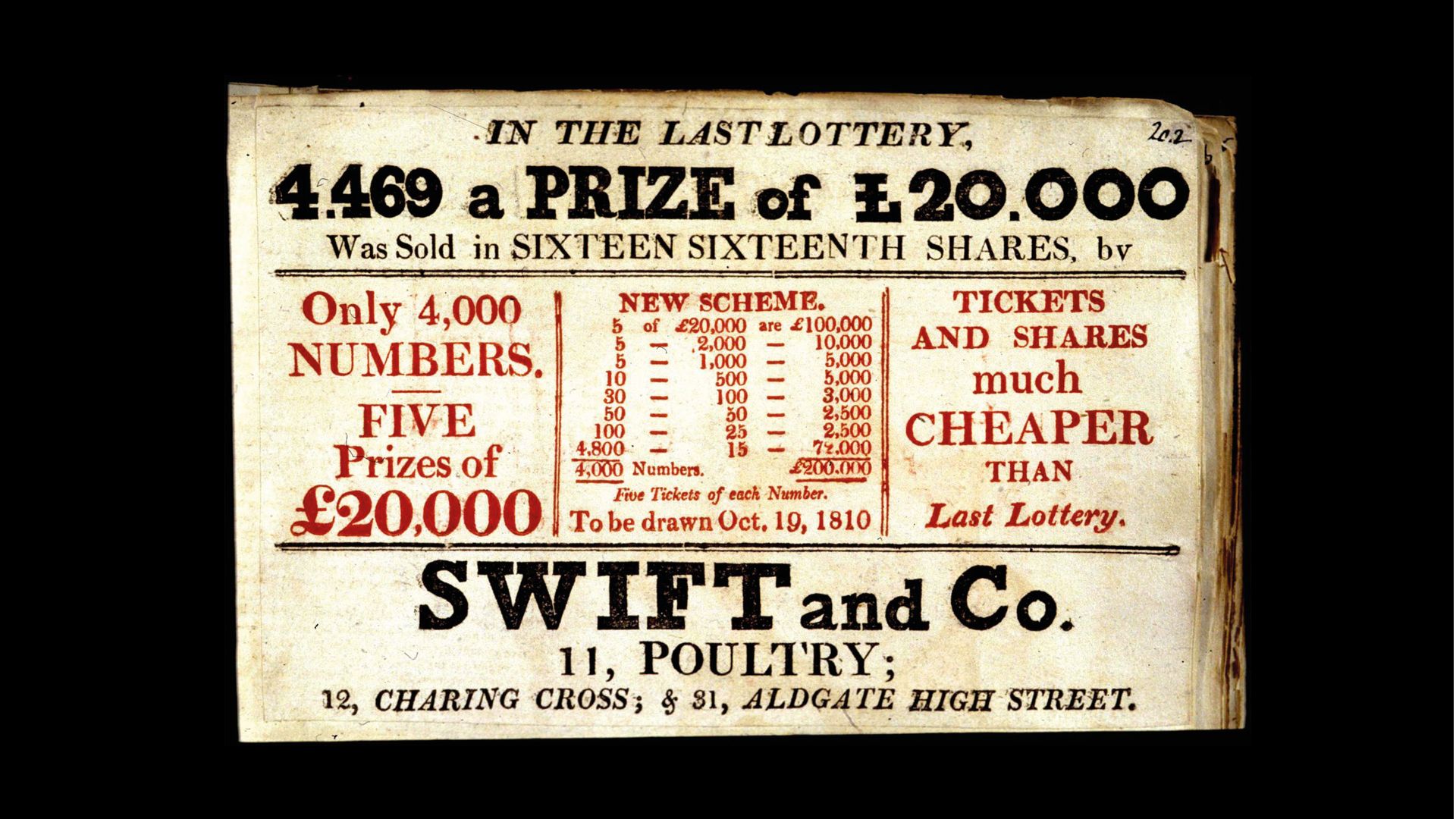

Thus, Fat Faces are wooden didones in large sizes, intended for posters and whose outrageous weight creates a black stain on the walls of big cities. Marketing of these fat types began as early as 1803-1816, but success came mainly around 1829-1850.

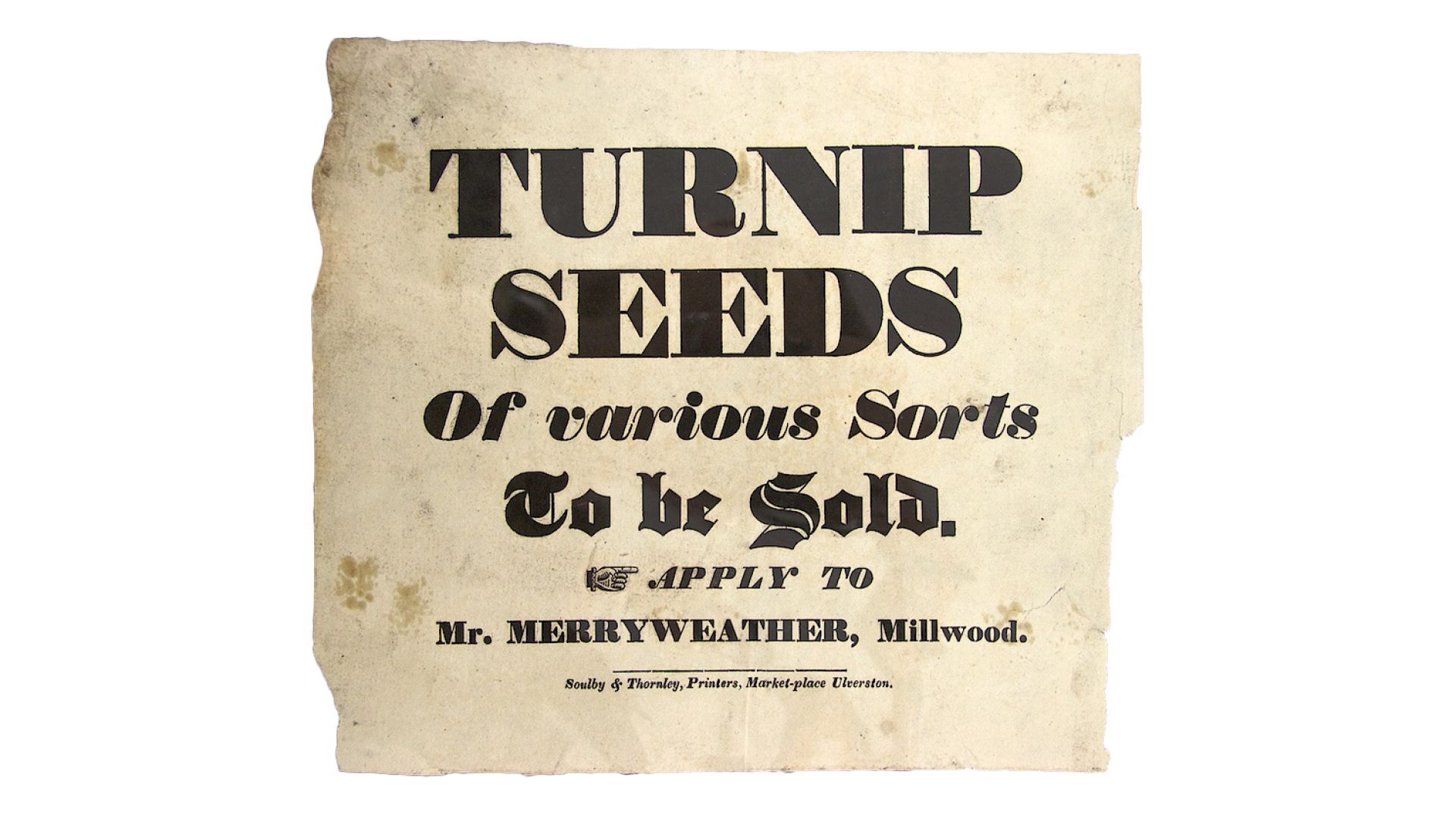

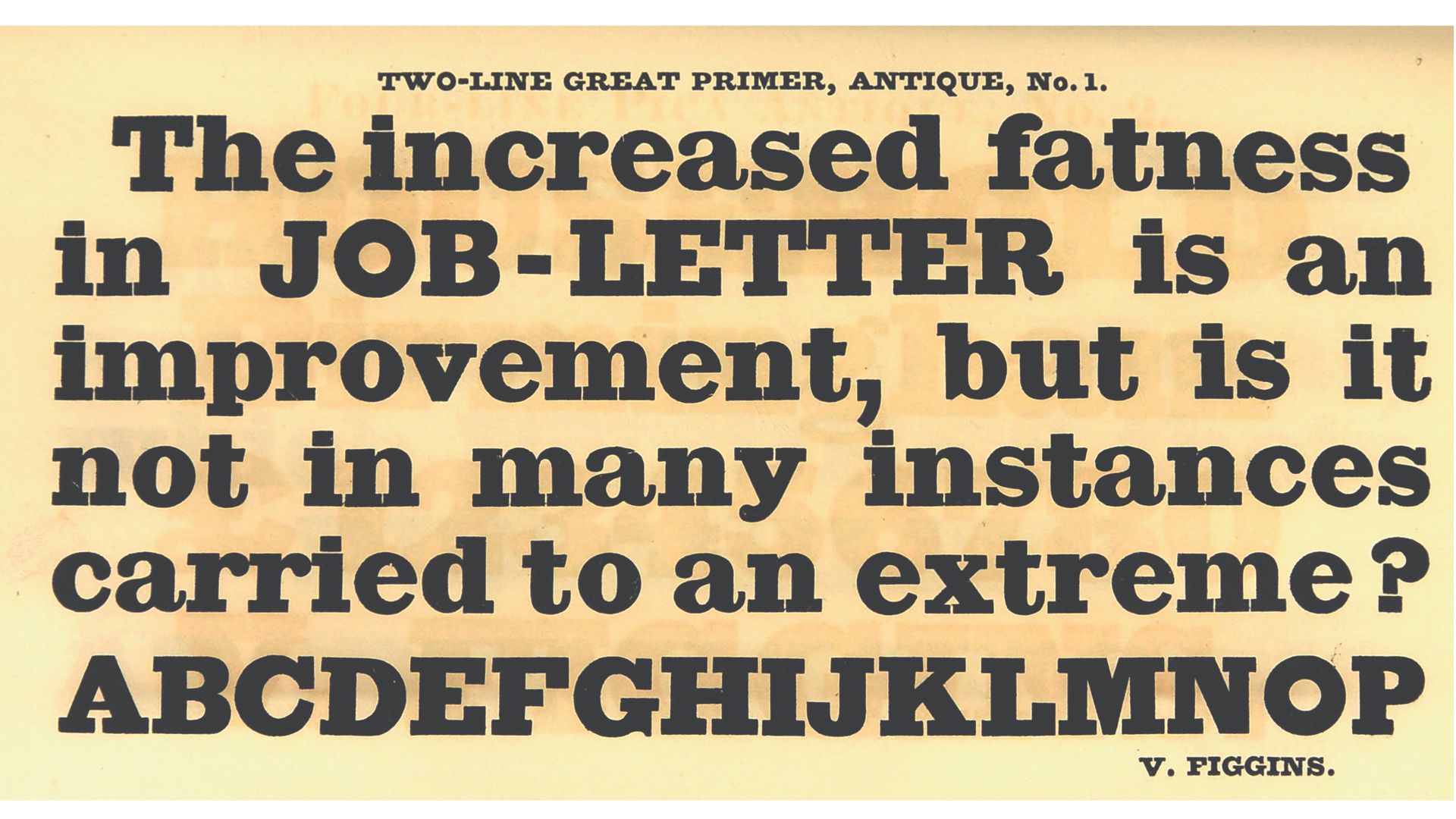

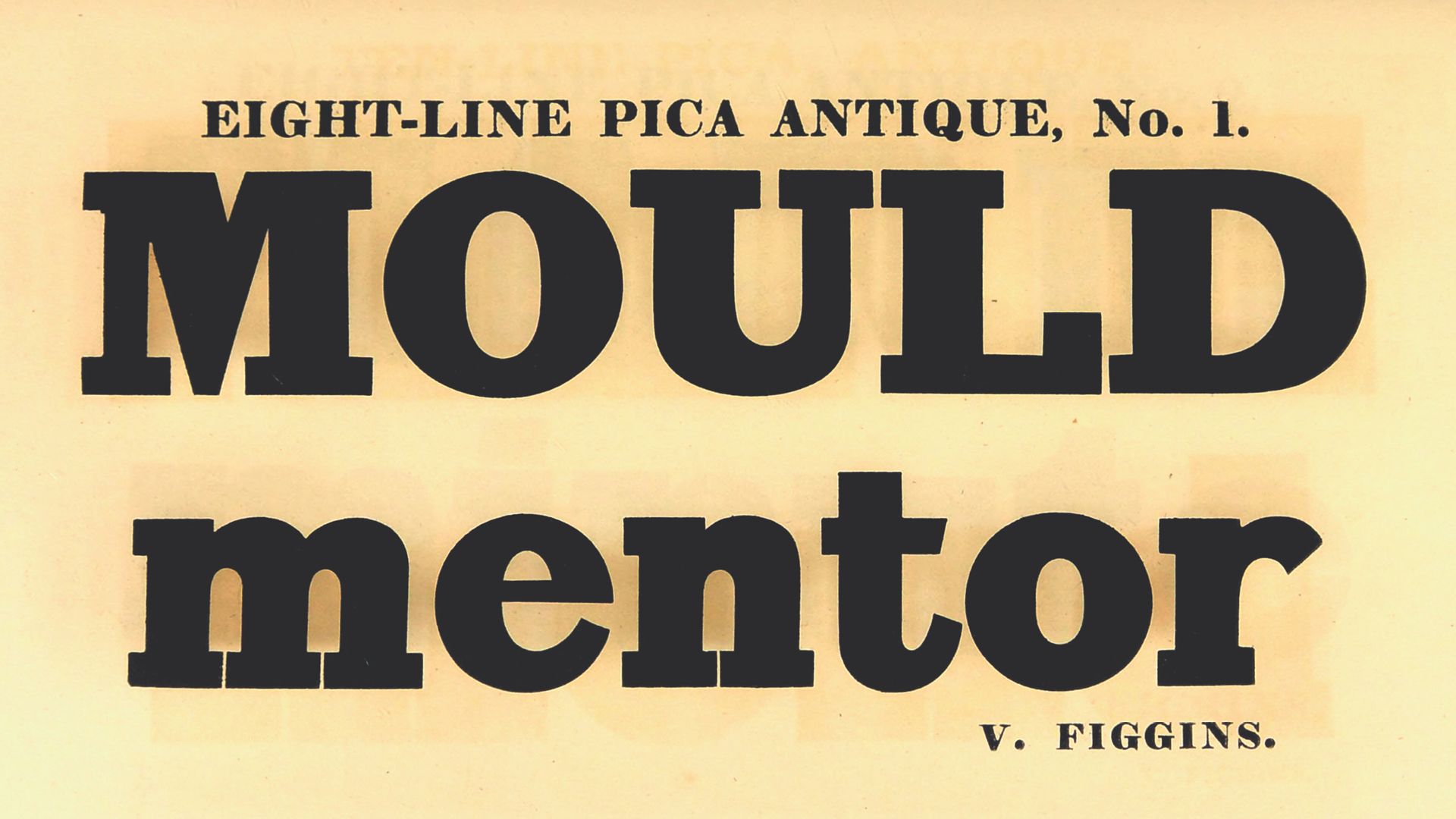

Probably in a similar, thoroughly modern move towards efficiency, the first slab typeface was released in 1815 by London type designer Vincent Figgins under the name "Antique". The design was not truly original or unseen, and a London lottery prospectus already shows wooden lettering in this style. Bold capitals and lower-case letters coexist with regular leaded text in Roman didones and italics, to the point where the whole remains coherent despite the brutality of the title and the organizer's logotype composed in slab.

These two examples clearly establish these slabs as natural evolutions of fat-doped didones whose serifs, usually thin like the Fat Faces, is adjusted to the thickness of the stems. Moreover, the variations in fullness and smoothness, though subtle, are still respected, as are the drop terminals visible notably on the a and c.

Egyptian & Sans serif: linearity and exoticism

Two important details make this investigation even more obscure. Firstly, the term "Antique", chosen by Figgins, has no logical basis. Never before in the history of writing has this type of thick, geometric serifs been used. Totally modern, why would anyone want to name them in reference to a past unknown to all? Secondly, Figgins' Antique has a completely circular and linear O and Q, where its other capitals still exhibit subtle variations.

At the crossroads of the 18th and 19th centuries, it's true that Antiquity enjoyed immense popularity, especially through the Egyptomania following Napoleon's campaigns in the country. Indeed, the first sans serif typefaces were named Egyptian, as were the first slabs. A coincidence due to an exotic trend, but is it as simple as that? What if sans serifs and slabs had a similar logic? What if slab were inspired by sans serifs to which serifs had been added? There's no information to confirm the hypothesis, but it's likely, from both sign painters and type designers, that it's easier to create lettering or typography slab from a sans serif model than to draw a didone with assertive boldness and thick serifs.

Thus, one would see a serif typeface named Egyptian, just like its model, to the point where confusion reigns between sans serif and slab.

Moreover, even Hofler & Frere-Jones are wrong about the typeface designated Egyptian by the poet Robert Southey, a sans serif and not a slab. But these authors rightly note the ambiguity of the typeface's design:

“In the earliest slab serifs, there’s little to suggest much forethought on the part of their designers. The typeface above, Figgins’ Two Lines Pica Antique No. 2 from his specimen book of 1838, gives the impression that its designer simply began with one letter and worked his way through the alphabet until the project was complete, never stopping to articulate the design’s policies or anticipate any problems. In many ways, this design is two typefaces, its uppercase and lowercase being almost wholly unrelated. The qualities of its steadfastly geometric O recur in the Q, but stop there: the other capitals exhibit a more modulated weight, from the N that differentiates thick stems and thin hairlines, to the S that continuously changes its thickness throughout the entire form. These characters may feel like exceptions that compromise the underlying rule, but in fact they set out a more sophisticated approach, one that would ultimately prove more fruitful than the rigid pursuit of mathematical consistency.”

Didone thick serif or sans serif serif, slabs quickly recognize both logics, sometimes within the same alphabet, sometimes in different typefaces.

The only notable problem is that the robustness of slabs serifs on small-body lowercase makes them an impossible character in its geometric construction. Indeed, these bricks make letter construction problematic if you want to keep the shapes open and linear. The only solutions: reduce the weight, break up the geometry by creating openings similar to inktraps, or reduce the size of the impasto.

The first solution would reduce type legibility. The second requires a real talent for type design and a good knowledge of optical corrections. The third requires a skilful dosage, otherwise serif will become incidental and detract from the overall coherence.

In the Italienne model, also known as French Clarendon type, the serifs are even heavier than the stems, forging a dramatic, attention-drawing effect. This is known as reverse-contrast type. It is traditionally associated with use in circus and other posters, and is commonly seen in Western films or to create a nineteenth-century atmosphere. It was most popular from the 1860s until the early twentieth century, particularly in the United States, although the basic concept originates from London printing of the 1820s and it was used outside the United States. It has often been revived since, for example by Robert Harling as Playbill and more recently by Adrian Frutiger as Westside.

Typewriter & codes

From this desire to create a slab body text typeface, the geometry of the letters had to be broken up and the serifs preserved. The result is more or less a small-sized didone, as robust as a Walbaum, but with thick serifs. However, another solution is possible, requiring a change of formal logic.

Industrialization also implied international trade, and written business correspondence capable of legibility without recourse to letterpress printing. In short, we wanted to write printed letters. The invention of the typewriter was a chronological and geographical chaos, with countless patents filed that rarely led to industrial production. Above all, one of the difficulties faced by inventors was to allow the printed sheet to advance according to the stroke of each character. Indeed, a i does not take up the same width as a m or a w. The solution is simple: the letters must occupy the same space. So, extending i with uniform, extended serifs fills the available space, and condensing m by also reducing its serifs shoehorns it into the same footprint.

Can we properly speak of slab for the typefaces of the first industrial typewriters? Probably not: the serifs are far too rustic, the typing and ribbon inking make the printing random and of poor quality to recognize a slab.

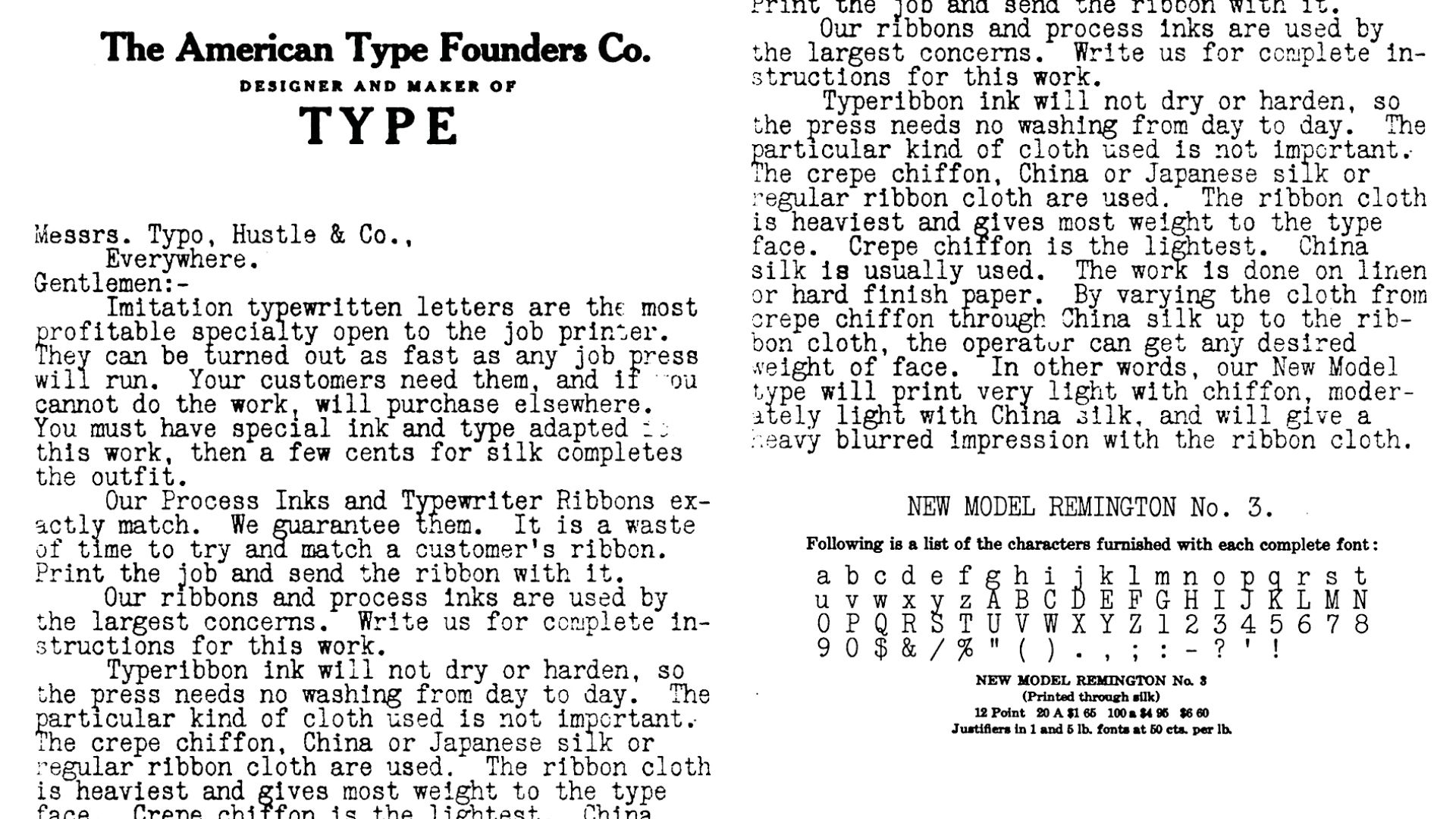

Yet in 1906, the American Type Founder Association published the New Model Remington n°3 after the name of the famous American firm. At the 12-point scale, the typeface's morphology becomes telling: the whole is inspired by a didone with uniform grease; the capitals appear condensed, and the serifs adjust to the free space around the letter. Not surprisingly, this typographic style with long, filiform serifs was also inspired by certain Victorian typefaces found on labels and commercial letterheads. The ingenious inventor of the typewriter may have found here a model for a narrow typeface that could simply be retouched on certain glyphs to obtain a graphic solution adapted to technical constraints.

In a logic similar to that of the typewriter, the first computers did not have a graphic interface, enabling easy reading on a low-definition screen with a restricted color palette. Computer engineers needed to be able to quickly find their way through volumes of raw text by graphically structuring the screen according to a set of indentations made up of spaces, hyphens and other symbolic characters. The solution is the unique use of monospace fonts, and thus of slab issues from typewriters.

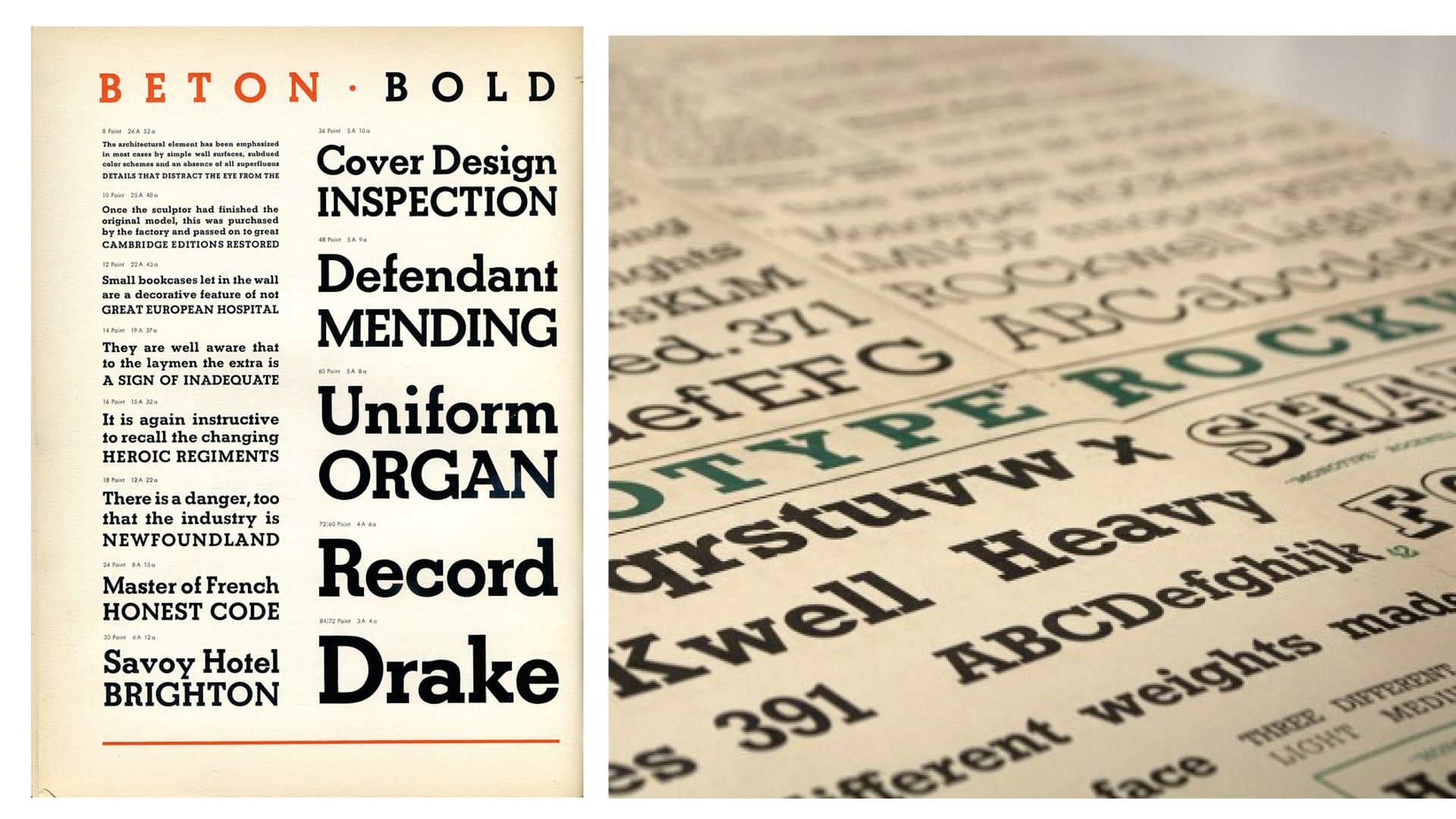

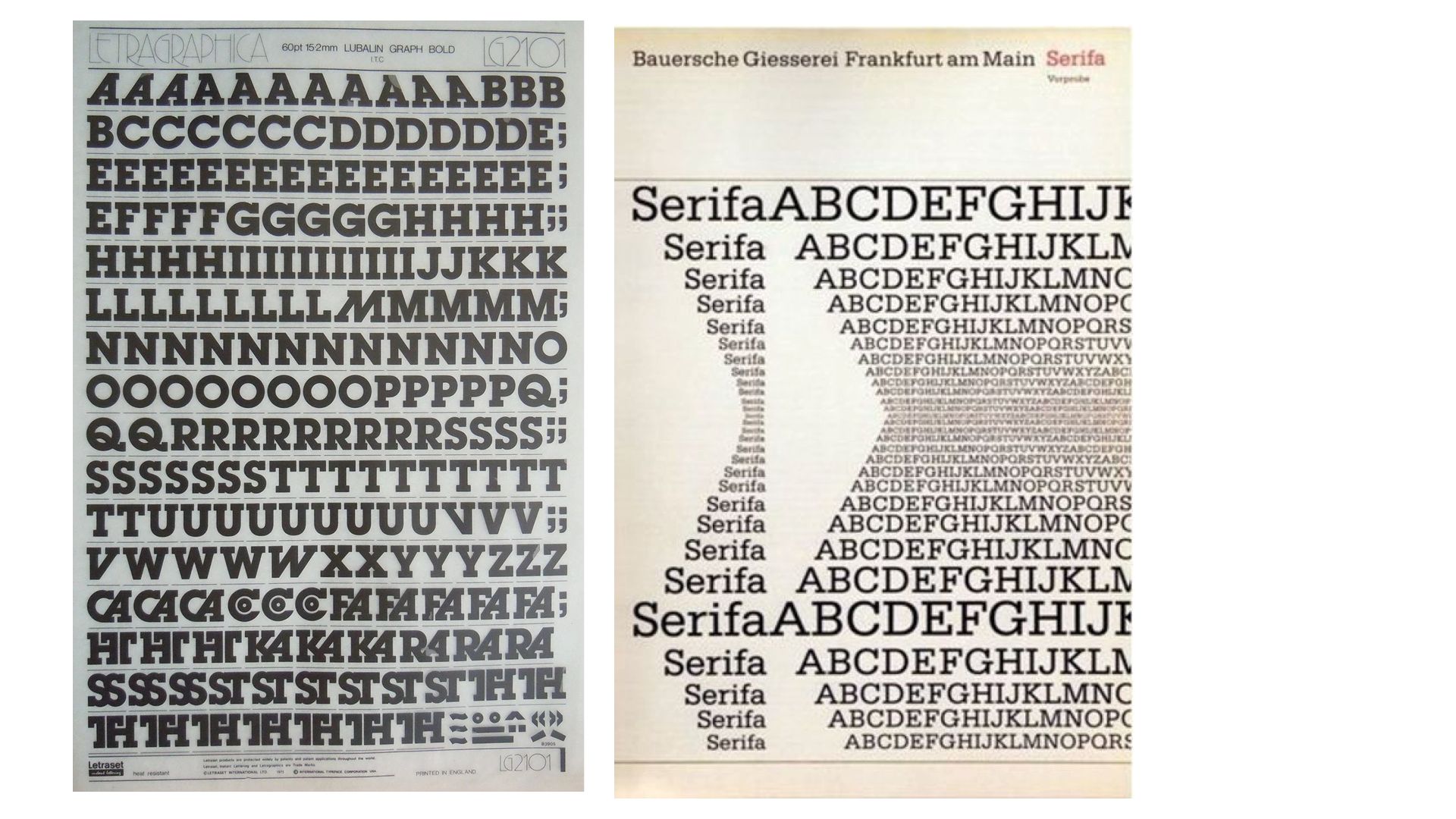

Following on from the rationalist ideals of the Bauhaus school, leading type designers were quick to see slabs as a typographic genre to be perfected. Thus, the success of Futura (1927) by Paul Renner (1878-1956), thanks in particular to its subtle optical corrections, was followed by a series of slabs: Rudolph Wolf (1895-1942) and his Memphis for the Stempel foundry in 1929, Morris Fuller Benton (1872-1948) and his Stymie for ATF in 1931, and Monotype with the Rockwell in 1933, Heinrich Jost (1889-1948) Beton (1931). More recently, Adrian Frutiger (1928-2015) designed the Serifa in 1963, then Herb Lubalin (1918-1981) declined his Avant Garde into the Lubalin Graph in 1974.

From a chunky advertising typography, slabs became the style of commercial writing, then that of early computing, optical character recognition software, then coder nerds.