By Sebastien Hayez. Published February 02, 2022

Swiss modernism & type design

Introduction

Swiss style was the main topic for graphic design nerds in the beginning of the 2000’, when blogs and social media were popping. The new css standards offer great possibilities for structuring the content and designing the webpage in a rational way. Using the structural and typographic grids was easier than before, but young designers were looking for some masters for a good use. And so Josef Muller-Brockmann and the Swiss style became a new trend. But what the Swiss masters can offer is not a matter of trend, it’s about organizing and structuring the world of content and datas. What is still relevant today. And if you know nothing about Swiss modernism, here’s a small compendium of Swiss Type Modernism.

Tradition for neutrality

Thinking about Swiss Modernism is understanding the general Swiss mentality. The country is divided by four cultures: the French language culture, the German language culture, the Italian language culture and the Romansh (spoken by 60.000 citizens). Switzerland is also the cradle of the Protestantism Reform, thanks to the presence of Calvin in Geneva and Zwingli in Zurich. This religion is based on five solae, five points. In the Reformed Protestants, there is a saying amongst theologians: “Ecclesia semper reformada”: the church must always be reformed. Here is a symbol of the tradition for modernity.

Regarding graphic design, Switzerland is considered as the land of neutrality. This concept could be defined as “neither this, nor this'” (neutrality, from neutral, from old French, itself from the latin word “neutrum”), it’s the rejection of both polarity in a choice, preferring not taking part of a basic opposition. Rooted in its history, Switzerland has been politically and military neutral since The Treaty of Paris signed on March 20th of 1815. Today, this political choice is attractive for foreign capital and international organizations.

In the graphic design surface of the poster or the page, neutrality means communication and not propaganda, nor advertising. Neutrality is giving, for example, the information regarding a political vote, the plus of a new car or just giving the lastest news; that’s why Swiss graphic designers defined themselves as “communication engineers”.

Modernity is without ornament

Before forging the term “Graphic design” and establishing the first professional cursus, the pioneers of design were trained as architects and painters. Their will was to continue the alliance between Art and Industry for the good fortune of the people’s life. Nothing surprising to see the first Avant Garde artists producing posters, book layout and logos around the first World War. The use of typography was divided in two philosophies.

First, the Italian Futurists said “We will glorify war—the world's only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.”. Its graphic design manifesto was searching for “freed the words” (“les mots en liberté”). Typedesign was not a priority and Futurists were choosing what printers had in stock to design free compositions with words composed of hazardous types, producing an explosive effect in the page. In the same radical philosophy, Dada, the German art movement, was also an anti-art protest but its graphic design ephemera is more classic.

The second philosophy was produced by Avant Garde from northern Europe, mainly De Stijl, Constructivism and Suprematism, plus the German Bauhaus school and the New Typography defined by Jan Tschichold. Following Austrian architect Adolf Loos, “Ornament is a crime” and suddenly modernity no longer needed decoration to create its own aesthetic. Layout was structured with lines and columns; sans serif fonts were preferred, and photography was preferred in posters, books or any design work because of its so called objectivity.

Graphic Design & Art: Art Concret

Surely most of the Swiss modernists prefered following the steps of the Northern modernists: structure, balance and sans serif typefaces.

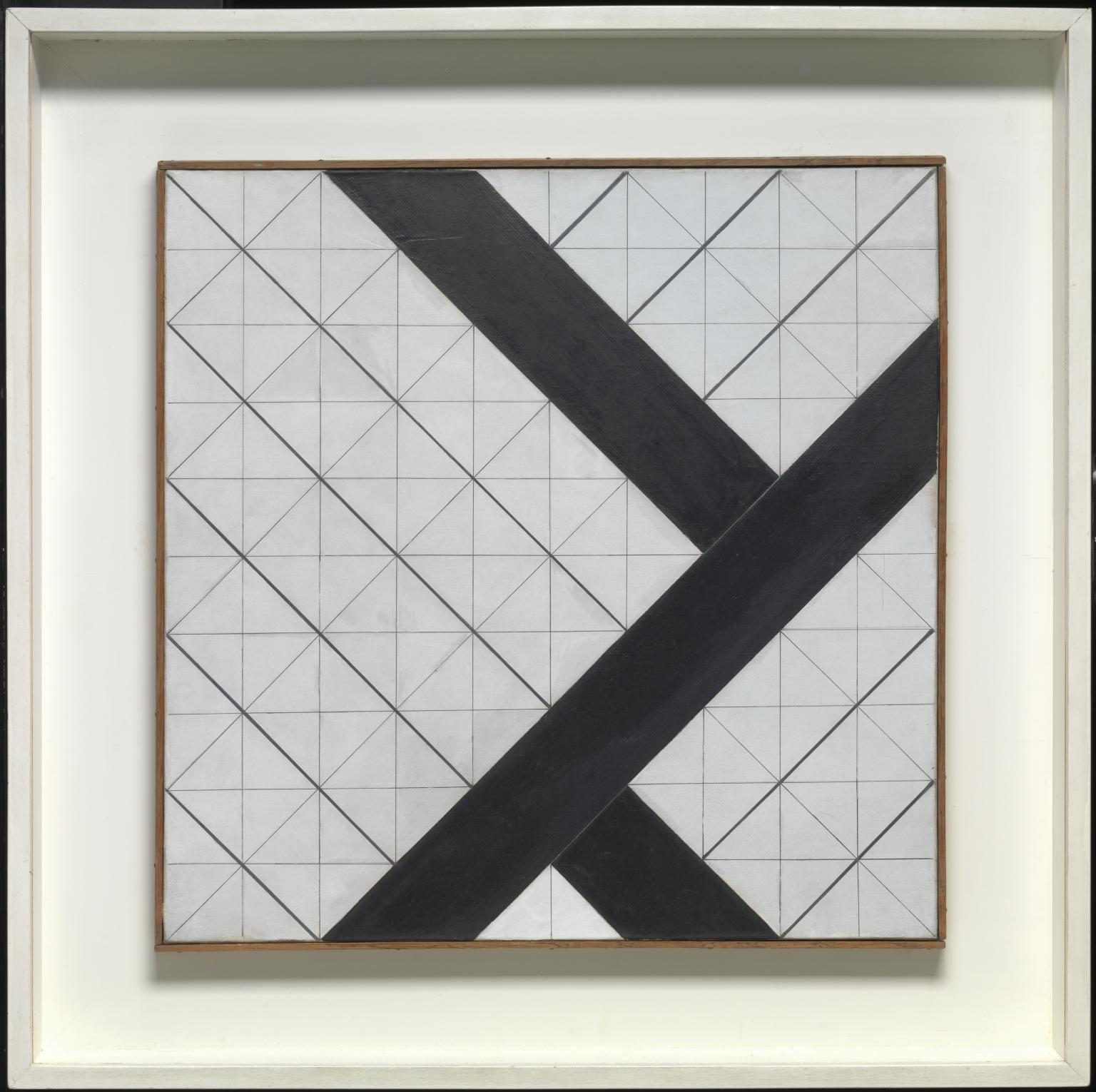

One of the fathers of Swiss modernism in graphic design was Max Bill (1908-1994). Trained at the Bauhaus, Dessau, he was both a graphic designer and a painter. In 1937, Bill and 8 other Zurich based Swiss artists were gathered under the flag of the Allianz group, promoting Art Concret theorized by Theo Van Doesburg, founder of De Stijl with Piet Mondrian. This style is a mathematical & geometrical abstraction, creating rational structure, color palette and hierarchy: everything that graphic designers need when establishing good communication tools.

Swiss Graphic design theory was greatly influenced by this art group, as some of its members were also the greatest Swiss graphic designers of the time, like Max Bill, Richard Paul Lohse and Max Huber.

The grid

The composition of the page, or the poster, is ruled by a rational organization. Neutrality is reached at different levels. The main goal is to create the frame for organizing and developing a global structure for a complex content, text and pictures. The industrialization of the production forced the design of many documents in a short time and without any automatisation tools. A grid system is the metric in the score of your page: the graphic intervals of your page. The grid offers a graphic system solving many problems while reducing the possibilities, in a way we could say that the grid system is a shortcut. The grid is not a modernist’s concept (the oldest medieval book was designed using such principles), but the Swiss theoreticians pushed the grid to a new step. In his book Grid System, Josef Muller-Brockmann demonstrates how a grid is the best tool to organize and create the condition of a good design, both on the surface of the page or the poster, but also in three dimension design like exhibition.

Swiss type design

Akzidenz-Grotesk

The Zurich based graphic designers were using a classical typeface of the first Modernism, Akzidenz-Grotesk released in 1896 by Berthold Type Foundry. Considered as the most influential typeface of this movement, Akzidenz-Grotesk was sold in the U.S. under the names “Standard” or “Basic Commercial”. Its drawing was influenced by Royal Grotesk, from Ferdinand Theinhardt, whose foundry had been bought by H. Berthold AG.

Some could argue using an old typeface was inappropriate while pretending to be designing a modern graphic design.

Fresh blood was needed and two more concurrents would be released soon after.

Adrian Frutiger

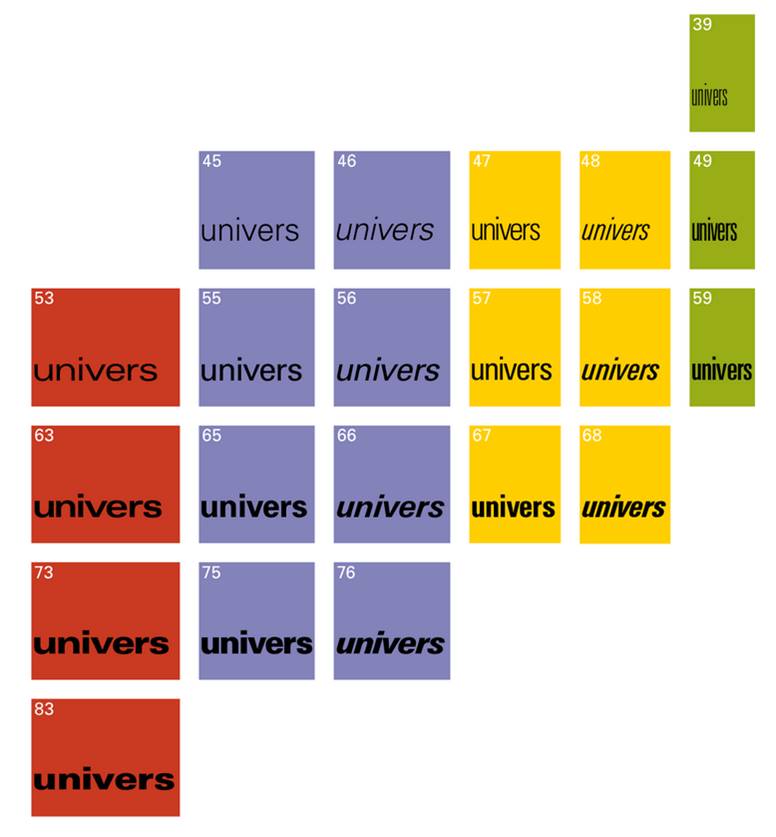

Adrian Frutiger (1928-2015) was a young Swiss type designer when he arrived in Paris in 1952, working for Derberny & Peignot. With Univers, he was designing a new sans serif typeface able to extend the range of a classic family to a brand new way of thinking and designing the weight and the various styles. Rationality was the main point: drawing a typeface was no longer a question of feeling but also a matter of program and extrapolation. More than changing our design habits, Frutiger changed our way of seeing design as a whole creative strategy. From Univers (1957), Frutiger (1976) and Avenir (1988), Adrian Frutiger is the author of some of the most iconic swiss modernist typefaces.

Helvetica

Neue Haas Grotesk, designed by Max Miedinger and Eduard Hoffmann in 1957, is the response for the need of a new classic sans. More than a revival of Akzidenz-Grostesk, it’s a radical creation with an extremely tight spacing producing strong words used when it was used for wordmarks. Neutrality was the argument for promoting the typeface: no cultural design element, the whole conception reflects the modernist philosophy of a suitable typeface for every need.

Quickly licensed by Linotype and renamed Helvetica in 1960 (as story goes, the US market would be more sensitive to a more generic name than “Neue Haas Grotesk”), the typeface became the most important Swiss emblem of the graphic design scene. But the medal has two sides and the overuse by the most important and international companies in their corporate identities also showed the limits of the modernist style.

Swiss design

Swiss design was so popular in the 160’s, that it became the International Typographic Style, and using the grid and some Swiss sans was the proof of a good design, or a proof of Zeitgeist. Critics were important. Especially in France, where designers like Maximilien Vox and his Lure group were preferring the latin influence. In the Netherlands, Jan van Toorn was also attacking the philosophy and the commercial importance of Swiss practice. But, the Swiss style was also evolving, with the help of some new masters, like Wolfgang Weingart, Wim Crouwel or April Greiman in the USA. No need to kill it, you just need to take the best part and be critical. That was what Swiss typography would become.

The popularity of the Swiss style is explained for multi contextual reasons:

the need for a rational method in order to produce good design quickly

the need for a communication method based on the illusion of neutrality and objectivity

the need of a new method in type design for designing large typeface family in a rational way

the ability for Swiss designers to educate graphic design students, and to publish manuals and books able to spread its philosophy and style

Some reading for exploring the Swiss style:

Manuals

The Graphic Artist and his Design Problem, Josef Muller-Brockmann, Arthur Niggli Verlag, Zurich, 1961.

Graphic design manual, Armin Hofmann, Arthur Niggli Verlag, 1965.

Typographie, Emil Ruder, Arthur Niggli Verlag, 1967.

A History of Visual Communication, Josef Muller-Brockmann, ABC verlag, Zurich, 1971.

Grid System, Josef Muller-Brockmann, Arthur Niggli Verlag, Zurich, 1981.

Manifesto

Neue Graphic, LMNV (Richard Paul Lohse, Josef Muller-Brockmann, Hans Neuburg, Carlo Vivarelli), 1958-1965, (Lars Müller Publishers, reprint in 2014), Verlag Otto Walter AG, Olten.

die neue Graphik, Karl Gerstner & Markus Kutter, Arthur Niggli verlag, 1959

Schwzeizer Grafiker, edited by VSG, Editions Kaser Presse, Zurich, 1960.

Moderne Werbe-und Gebrauchs-Grafik, Hans Neuburg, Otto Maier verlag, 1960.

History

Swiss Graphic Design, Richard Hollis, Laurence King Publishing, London, 2006.

100 Years of Swiss Graphic Design, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Christian Brändle, Renate Menzi, Arthur Rüegg, Lars Müller Publishers, Zurich, 2014.

Mapping Graphic Design History in Switzerland, Robert Lzicar & Davide Fornari (Hrsg.), Triest verlag, 2016.

About the article’s author

Sébastien Hayez was an art director and graphic designer before becoming an art teacher and an independent researcher in the field of graphic design and type design history. His main topics are the history of logos, square books, modernism, and the minimalist italian designer AG Fronzoni 1923-2002. You can read his contributions in the pages of magazines such as Etapes, TheShelf Journal, Pli, Kiblind, Yellow Submarine, Fiction, or listen to his lectures for Les Rencontres de Lure or Fonts & faces #7.