By Sebastien Hayez. Published January 04, 2022

Serif: deviation & progress of a norm

Introduction

Type design is a matter of balance, of caracter through characters, shapes expressing style. While designing a new font, the first question might be : “serif or sans serif ?”. And the whole type taxonomy is mostly a question of serif’s morphology.

But I was surprised that no one was questioning several points about serif. So, let’s ask the usual questions in order to learn more about this essential word : why, when, how.

A young type design student should say that a serif is “a slight projection finishing off a stroke of a letter in certain typefaces”. This short definition should sound quite satisfying for anyone as it, in fact it comes from a dictionary. And if it was enough, we should all be able to place serifs every now and then in order to create something fresh and funny. If you'd like to give it a try, you should see that the final result would look like a good idea, still, expressed in the most chaotic way.

That’s perhaps because serifs are useful or at last have a raison d’être, as one says. Some dictionaries are arguing that serifs are useful for legibility. Chicken or egg problem : are we used to reading texts with serifs often placed at the right place?

Etymology of the Serif

The word’s origin is quite obscure, but recent in regard of type history. The book The British Standard of the Capital Letters contained in the Roman Alphabet, forming a complete code of systematic rules for a mathematical construction and accurate formation of the same, 1813, by William Hollins, used the word "surripses", usually pronounced "surriphs", as what we call serif. The book also proposed that "surripsis" may be a Greek word derived from σῠν- synonym, "together" and ῥῖψῐς, rhîpsis, projection.

The Greek scholar Julian Hibbert was talking in 1827 of “syrifs or cerefs", while describing the serifs designed by Bodoni. But Thomas Curson Hansard, as a printer, referred to them as “ceriphs” in 1825. The oldest citations in the Oxford English Dictionary OED are 1830 for serif and 1841 for sans serif. This distinction and the evolution of the spelling is the indication that the word, during the industrial era, is more popular, as the progress of industrial printing technology and the need for printing is creating a new market for advertising, communication and also for type design.

The Barnhart concise Dictionary of Etymology 1995 is going in the same direction, explaining that the origin is perhaps borrowed from Dutch schreef attested in 1350, meaning “line, stroke from Middle Dutch scrēve, see SCARP”.

The French word meaning Serif is Empattement, which can easily be understood as a small paw or a foot placed at the basis of the letter.

Origin of the Serif

Our latin alphabet was fixed for some centuries and the roman capitals from the Trajan’s column represents an ideal for all the type designers looking for the right balance between style and elegance.

Edward Catich 1906-1979 is the man who studied in depth how those letters have been produced. He was an orphan when he learnt sign-writing under Walter Heberling. After graduating high school in 1924, Catich studied Art at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1926 till 1929, then he received a Master’s degree in art at University of Iowa. In 1935, he traveled to Rome to study at Pontifical Gregorian University for the Catholic priesthood, where he also made a study of archaeology and paleography. That’s during the late 1940s and the early 1950s that Catich began exploring the Trajan column and its wonderful Roman Capitals.

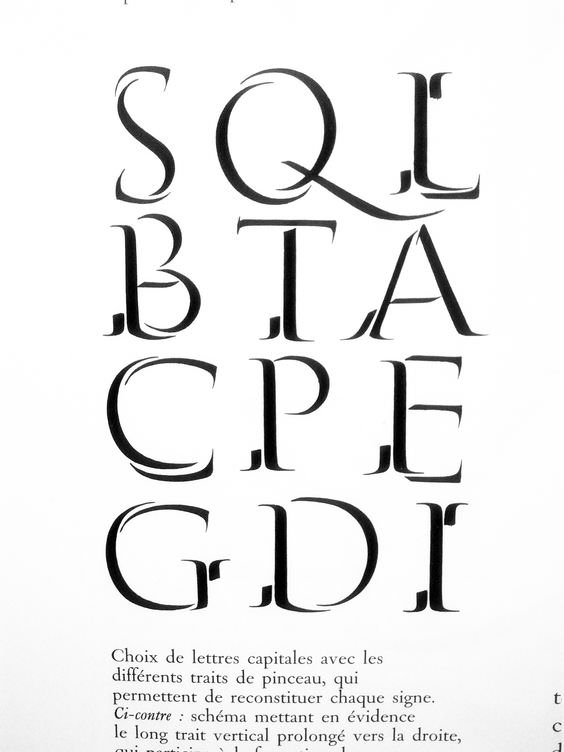

In 1961 he published his first book explaining his thesis on the origin of serif, Letters Redrawn from the Trajan Inscription in Rome The Catfish Press, 1961, then in 1968, The Origin of the Serif: Brush writing and Roman letters The Catfish Press

For him, his researches demonstrate that the roman lapidary engravers were calligraphing the letters on stone with a flat brush called spatula, probably with a red paint. Then, when the whole text was fixed, the engraving begins with the chisel following the spatula’s ductus. In a way, for Catich, the serif exists because of the spatula and not of the chisel. Stone engravers mostly disagree with Catich. They argue that the practice is the best demonstration and they pretend that the tool explains a lot of things. Both can be right, Catich versus the artists, because both tools are flat and rectangular. If the ductus and the handling is quite similar then the result should look similar.

Claude Mediavilla, in his book Calligraphie, explains that the serif is not the property of the Trajan letters, and Catich explored almost the Trajan letters only. Serif appeared in the greek inscriptions of the IIIth century AD and at IIth century AD latin text with serif were written without the help of any spatula.

(Screen above is available at this URL)

What’s seems to be clear, you don’t need to have a chisel nor a spatula to draw a serif letter. And having a chisel doesn’t mean the letter engraved on stone will have serif too.

These arguments operate on a great point: a serif, like a letter, is drawn, not only traced well, tracing is the beginning of drawing. That also means serif can have various shapes and proportions.

The serif placement is a matter :

of construction: because it helps ending the shape in an elegant way;

of balance: because it creates a basis for some letters;

of aesthetic: for some type family, like mono, serif can be added to a extend the width of a glyph

of legibility: scientific studies show that serif accentuate the differences between caracters. For a small size text, or a long text, the reading is more easy than with a sans serif typeset: That’s a general assertion that needs a proper context to be verified.

Evolutions of the Serif

The evolution of the serif’s shapes could be described in a two step history. First it was a slow transformation due to the evolution of the calligraphic style, its tools and its supports, then a faster evolution due to the technology and the commercial needs.

The Roman capital is still the model of many typefaces for latin script while the lower cases remains closed to the early Renaissance models inspired by the carolingian script

The tool is no longer the spatula nor a chisel, but a flat calligraphic pen, a reed pen or a calligraphic feather pen, that can be used to draw roman capitals or most of the script till the end of the Renaissance. Then, the nib calligraphy pen allows a simple variation of width with the pression of the tool on the paper. The serif produced with this tool is now different, smoother and mostly transformed when the quick script is becoming an italic script.

Type Design is a mirror of this calligraphic evolution: from Granjon to Fournier or Plantin, the serif were slightly polished regarding aesthetic evolution & mentality and national cultures. Didot & Bodoni are well known to be the first to push the boundaries so far that the evolution of the paper production were made in order to print correctly hairline serifs,

Sure, some styles appear because of political wills: the carolingian script is the will of Emperor Charlemagne to create a new calligraphic style to uniformise the various regional scripts and to erase the merovingian script dominion with a legible and easy to decipher style. More frequently, political powers would try to put their hands on some new styles for propaganda purposes.

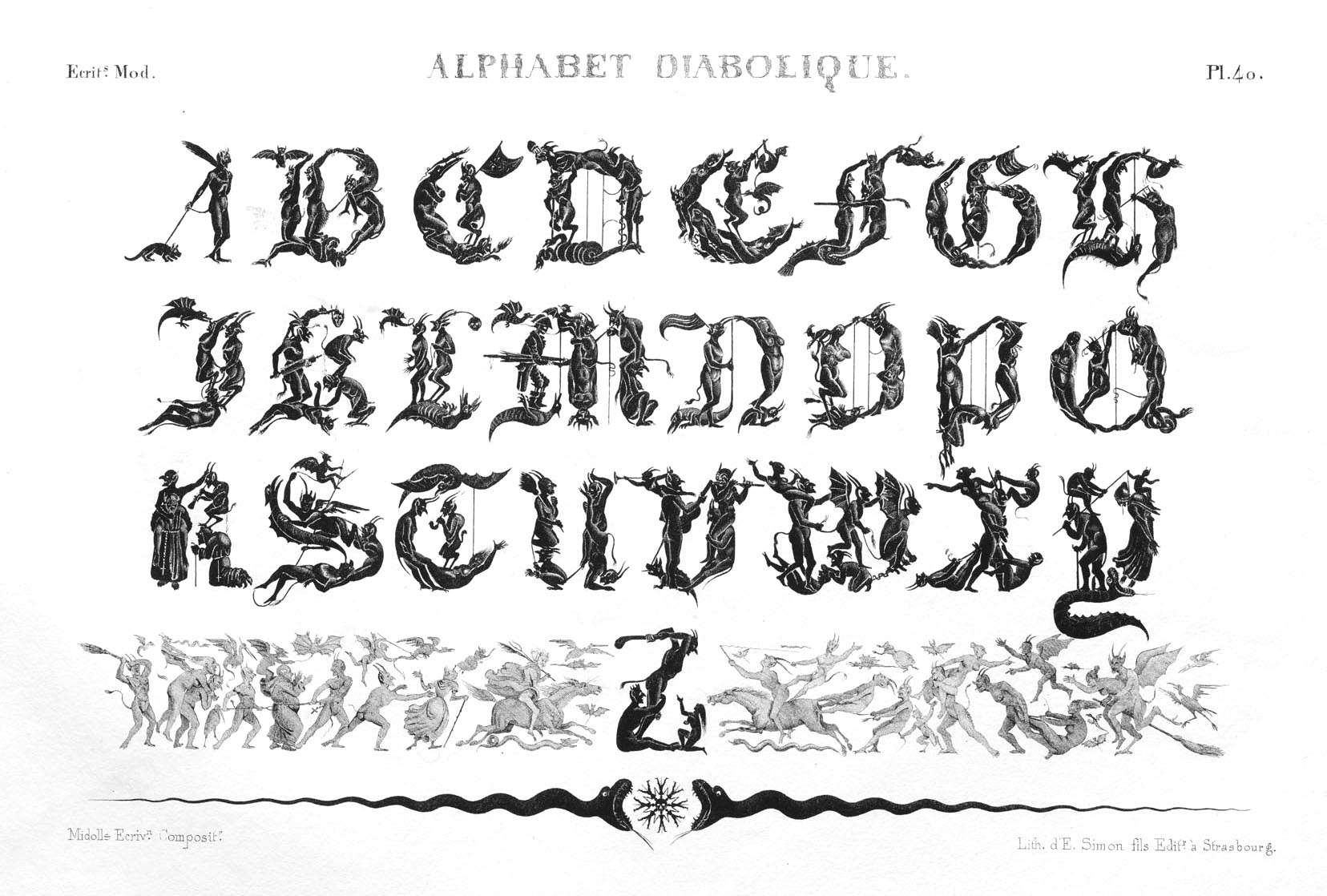

Since the Industrial Revolution, type design is no longer a matter of fine art craftsmanship. Lithography allows artists to include lettering within the illustrations, creating a unique style of composition, but also monstrous letters. The appearance of industry, as well as democracy, create new needs for newspapers, posters, labels, stationery, wrapping papers, etc. Printers began to include creation studios in order to offer quality, both in conception and production. Being able to offer new modern typefaces was the first step to be identified as a better manufacturer than the concurrent when the machines and the workers were mostly the same. Type foundries appeared in the mid of the XIXth century as creative studios offering the weirdest type explorations. Serifs could be shaped with a very traditional approach, a radical evolution or a teratological phenomena: monsters everywhere in the Barnum of early Modernity.

The most incredible serifs were mostly produced for wood type, used to print headlines, advertising and posters, some were also produced to be overprinted in two or more colors, as the Zebrawood typeface.

Lithography was also the printing technique able to free the artistic mind. Artists were drawing on the same plate pictures and letters, while the traditional printing press was separating movable character and wood engraved illustrations. Lettering was sometimes the first step before extending the character set to a real wood font for posters or headlines.

What remains clear is that serifs are never mandatory but should be able to add a feature essential to express a chronological reference, a mood or a feeling, that’s another chapter, coming soon, or at least some legibility. Drawn with a hand tool or a software, serifs are like everyone: different, weird or wise, classical or futuristic, but never really monstrous.

About the article’s author

Sébastien Hayez was an art director and graphic designer before becoming an art teacher and an independent researcher in the field of graphic design and type design history. His main topics are the history of logos, square books, modernism, and the minimalist italian designer AG Fronzoni 1923-2002. You can read his contributions in the pages of magazines such as Etapes, TheShelf Journal, Pli, Kiblind, Yellow Submarine, Fiction, or listen to his lectures for Les Rencontres de Lure or Fonts & faces #7.