By Sebastien Hayez. Published December 13, 2023

GR20 Paris

Can you briefly present your studio ?

Gr20 is a graphic design studio founded in 2009 by Cyriac Allard, William Hessel and Claire Huberdeau.

Having met at the Paris School of Decorative Arts, we each started out independently in different fields (editorial/magazine, photo gallery/digital design, visual identity/brand communication). Today, this complementarity allows us to have an extremely polymorphous practice of design and rich collaborations with other players in the creative world. Cyriac has left the studio, which now consists of 5 people.

Area font used for the exhibition signage, catalog, merchandising.

What is your sensitive relationship to typography?

It seems to us that typography, among all the other tools at our disposal, is the vector that infuses the project in the least conscious way.

In the sense that color and image are much more readily understood by the client or the receiver; each will easily comment on one or the other, putting words to make the link between them and their impression of the project.

The expressionist impact of the typographic choice is more secretive, more difficult to grasp.

Perhaps that's what we like so much about it: of all the tools, typography is the one that seems most suited to the graphic designer. Not in the sense that its use and codes are reserved for experts, but in the sense that, on the contrary, typography immediately colors for everyone, without seeming to.

Area font used for the exhibition signage, catalog, merchandising.

Your typographic crush when you were a student or young graphic designer(s), when you didn't know anything about typography? Why did these letters strike you?

WH: For my part, it took me a very long time to appreciate typefaces. It's a world that impressed me for a long time, and from which I felt excluded. Then I learned to look at typographic shapes without being paralyzed by the weight of history or convention. It's not uncommon now for me to fall in love with a typeface to the point of buying it without using it directly for a specific project. As a student, I'd say the first typeface that made an impression on me was Knockout (designed by Hoefler and Free Jones back when they shared a foundry), and in particular the sonorous use Paula Sher made of it at Pentagram for the New York theater public. One day, we were drawn to an unpublished Berthold Wolpe character: the Pegasus. We fell so in love with this typeface that we asked Matthew Carter to send us a version he had made for an exhibition catalog. There was only one typeface, and not all the characters were present, but we used the typeface for the entire graphic design of a literary magazine! We later bought the complete version designed by Toshi Omagari for Monotype's Wolpe collection.

CH: The diabolical "s" of the Didot Elder struck me. Didones don't attract me any more than any other typeface, but I'm often drawn to a typeface by a detail before I perceive the whole. The freedom that can be taken in the micro-drawing of a tiny piece of lettering, and the way in which this freedom will infuse the expression of a whole - even though this detail will escape many of its readers, is fascinating.

I've never designed anything with Didot Elder. But for our first commission with Cyriac, we turned to Optimo: we built the identity of the Capricci collections from Philipp Hermann's La Piek. We hadn't considered the cost of the license... I found it in an envelope under the Christmas tree!

Area font used for the exhibition signage, catalog, merchandising.

Do you have rules, dogmas, that you apply every day and that you don't want to question?

No preconceived rules.

The graphic designer or artist you would like to talk to over a meal?

WH: Meet the lapidary engravers who created the base of the Trajan column. How many of them were there? How did they make their graphic choices in the shadow of the spiral images above their heads? What were the reading conventions, rules, tastes and prohibitions of the time? What room for maneuver did they have in terms of graphics, the link between textual content and graphic expression? How were they viewed by other sculptors? We'd picnic on dried fruit, wear little sandals and togas, and have a very calm, geometric time.

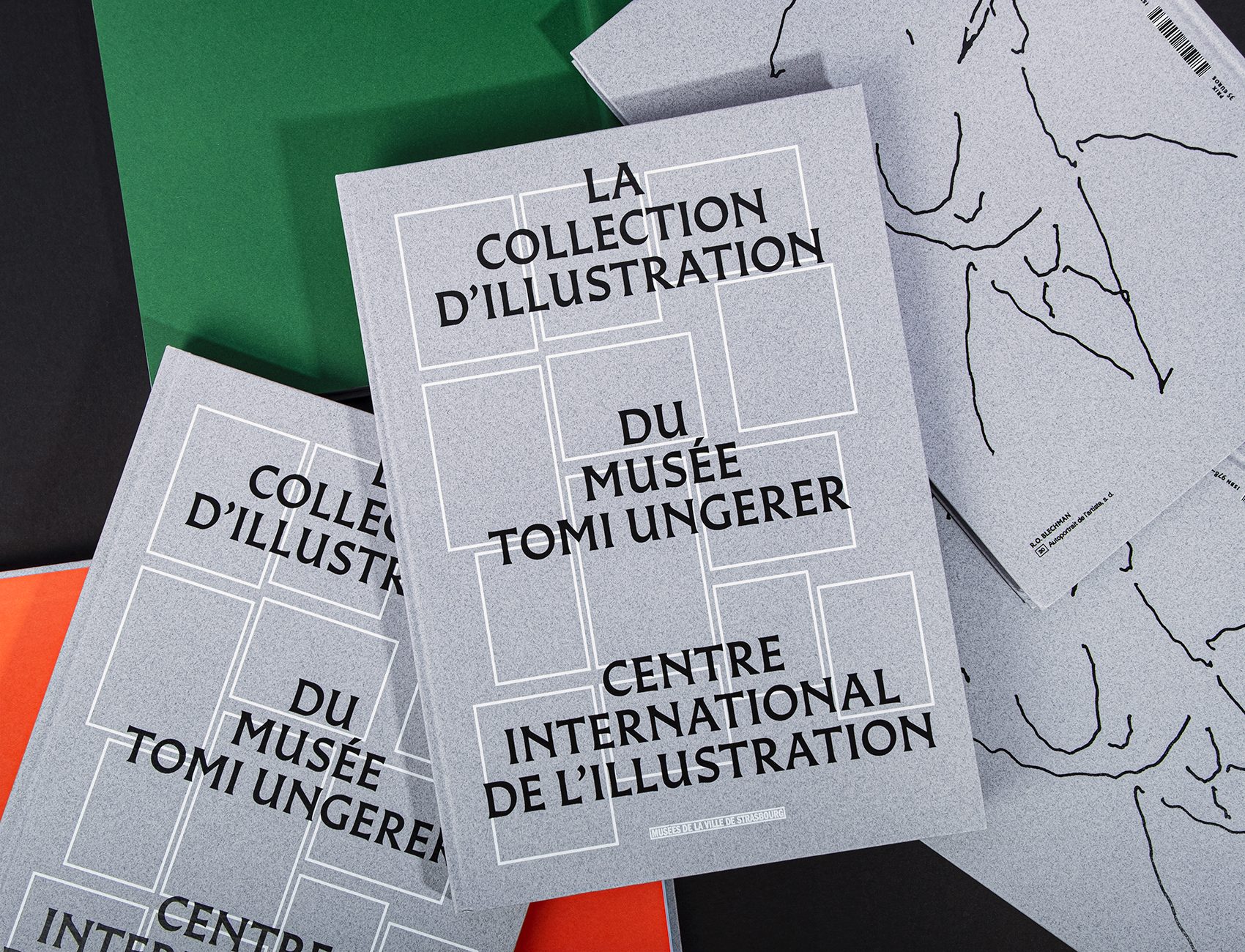

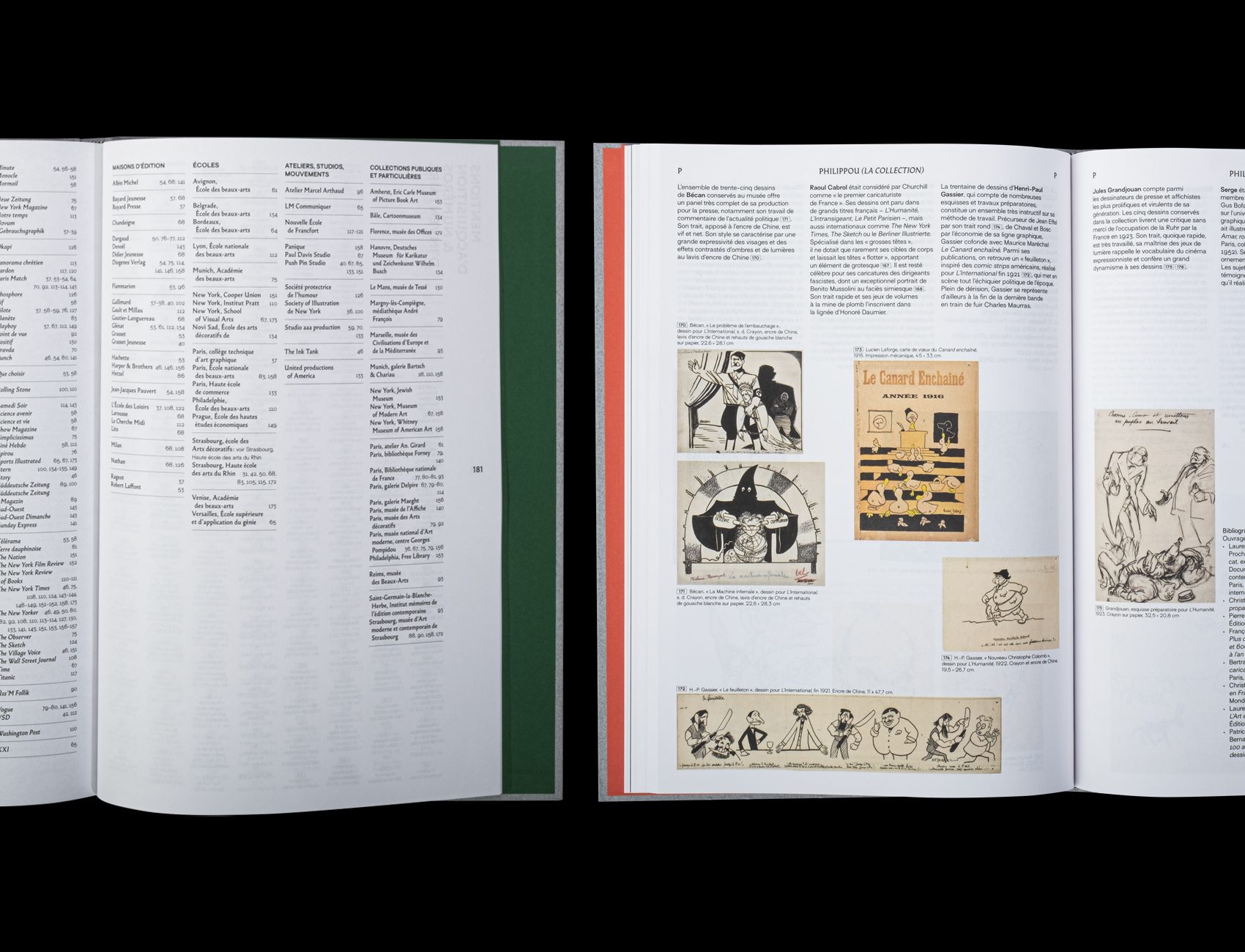

Catalog of the Toni Ungerer's museum illustrations collection.

You've used Area and Surt for the commercial typography of two publishing projects. Do you have a predilection for Sans Serif fonts for this type of use, or are your choices guided by each project?

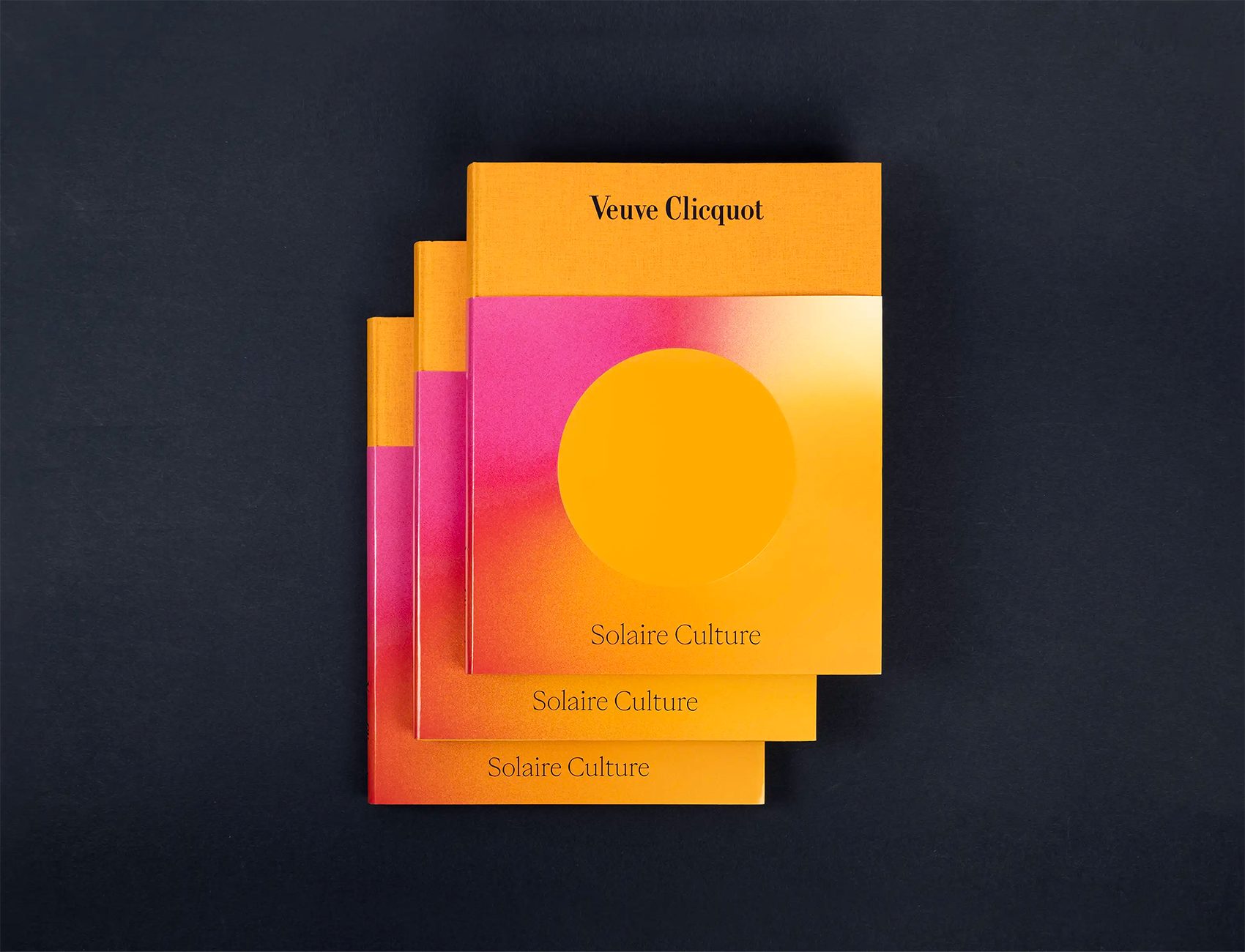

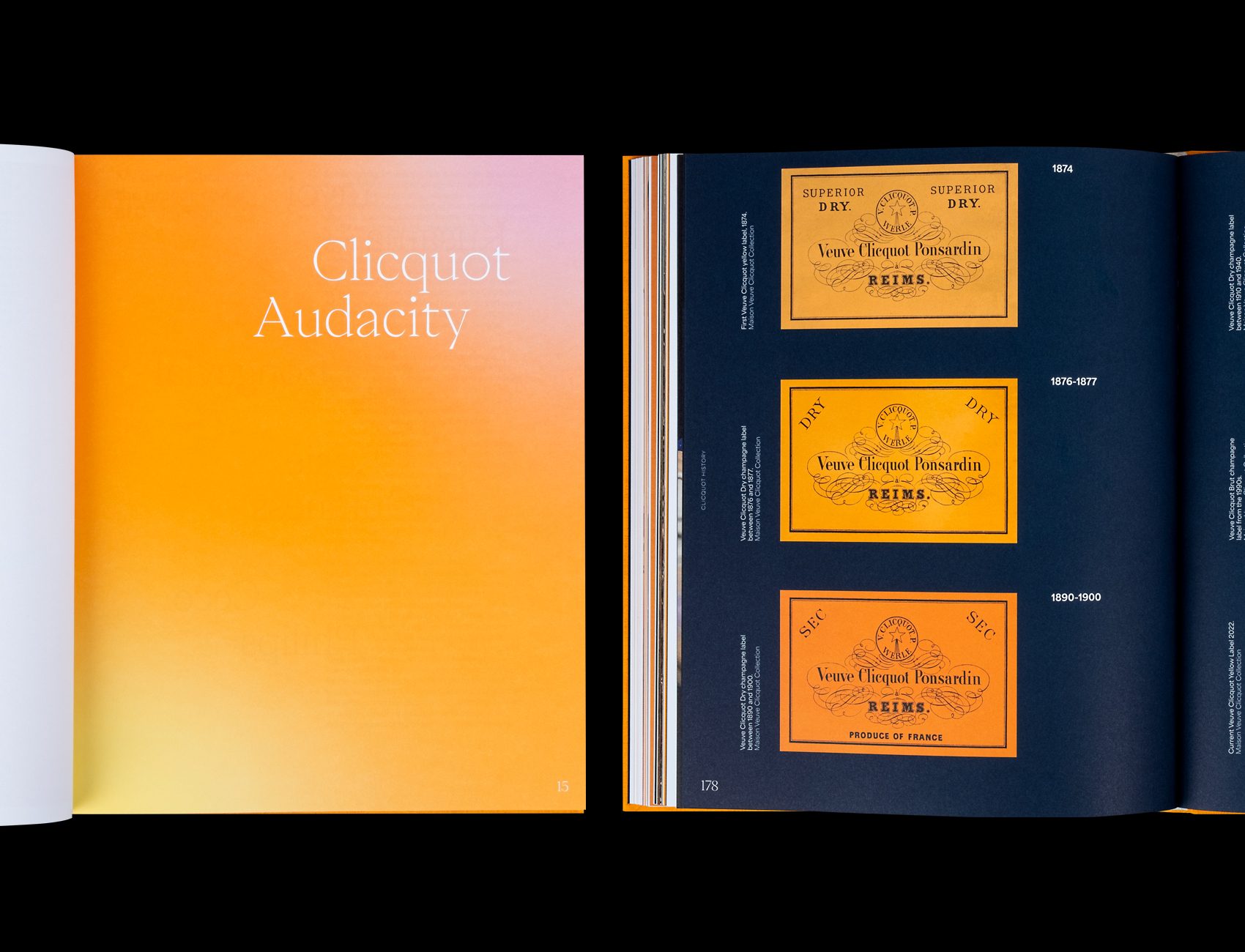

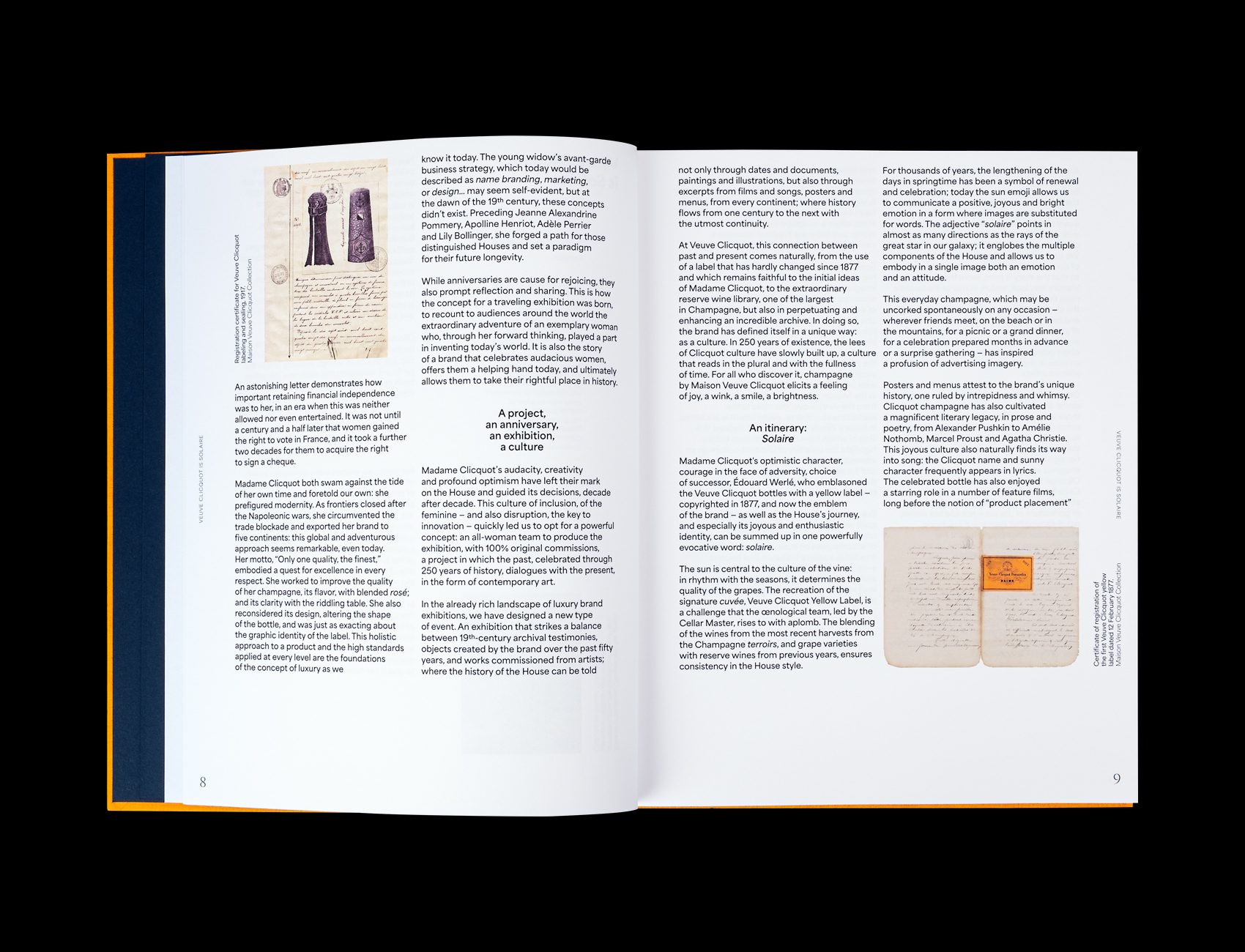

As a general rule, we like to use typefaces in pairs as contrasts, mirrors or counterpoints. For example, the brutality of Surt was very appropriate in relation to the elegant, robust typography of Jérome Knebusch (Almost typeface at Poem). For the exhibition and catalog celebrating 250 years of Veuve Clicquot champagnes, we used Area in body text and caption to counterbalance the titles and caps in Eiko (Pangram Pangram).

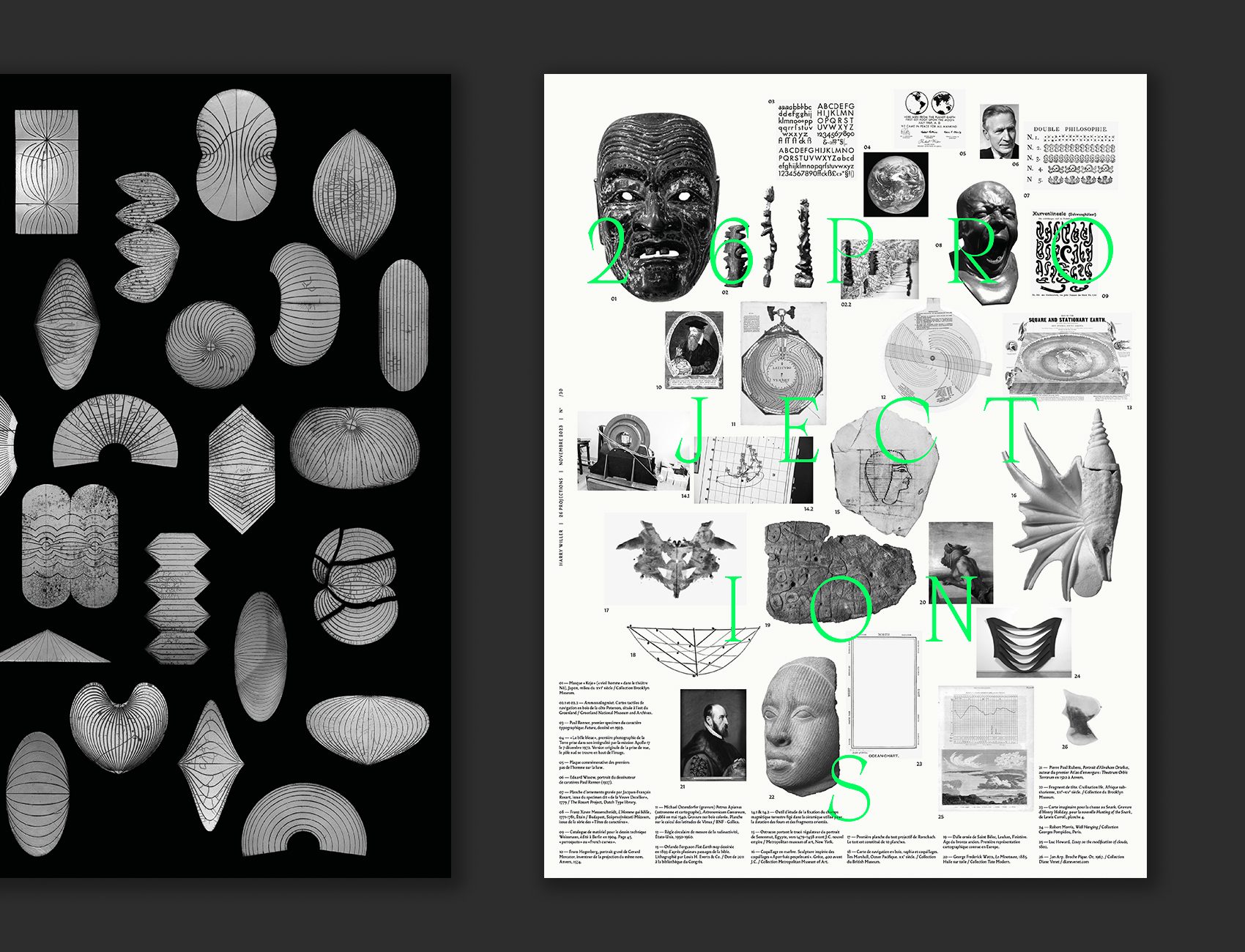

WH: Alongside my work as a graphic designer, I create ceramic plaques under the pseudonym Harry Willer. I used the APOC in its "revelation" version to title a series entitled 26 Projections. These tormented forms accompanied me for a poster that synthesizes this series.

Your use of typography seems relatively modernist: very sober, importance of construction over and above the expressive or ornamental aspect. Isn't typography just one of the tools in your toolbox of graphic signs?

It's quite interesting that you should evoke a modernist, sober approach, because we feel, on the contrary, that we're quite lyrical in our use of typefaces! What you say is very true: typography is an equal part of all the ingredients at our disposal (iconography, color, the materiality of the support, etc.). Nevertheless, it has a special place in the life of the studio, as it often initiates the conceptual orientation of the project. The more we work, the more decisive and certain our typographic choice becomes: it's very often well received by the client. We don't hesitate to opt for a specific type design as soon as it seems obvious to us.

Catalog of the Toni Ungerer's museum illustrations collection.

You're equally at home in editorial design, global branding (from location to logo), scenography and animation (Hermès). Is this a project-related need, or a desire to diversify?

Yes, we mentioned above the origins of the studio's polymorphism. It's not a will, but a state of mind: we don't see any hierarchy in the fields of application of graphic design and would like to see the boxes loosened more readily in France.

Each project invites us to broaden the spectrum of our work, and we like to push ourselves in this direction. Whether it's making metal price tag spikes, wallpapers, mobile billboard supports, or even graffitiing the entire facade of a public institution in Belgium... we're always on the lookout for new service providers/collaborators.

For us, it's a question of constantly expanding the territories of expression, of communicating intelligently in every place.

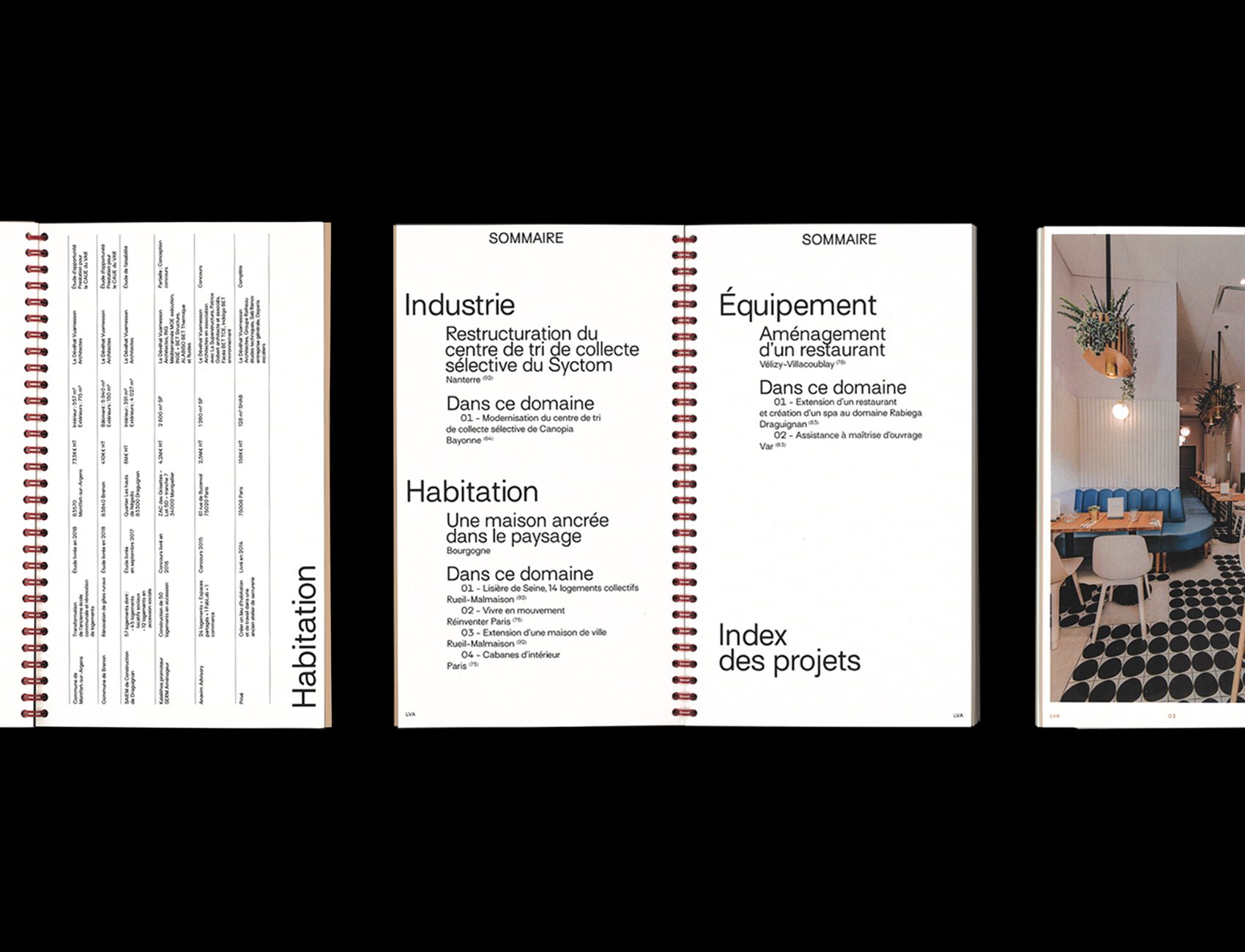

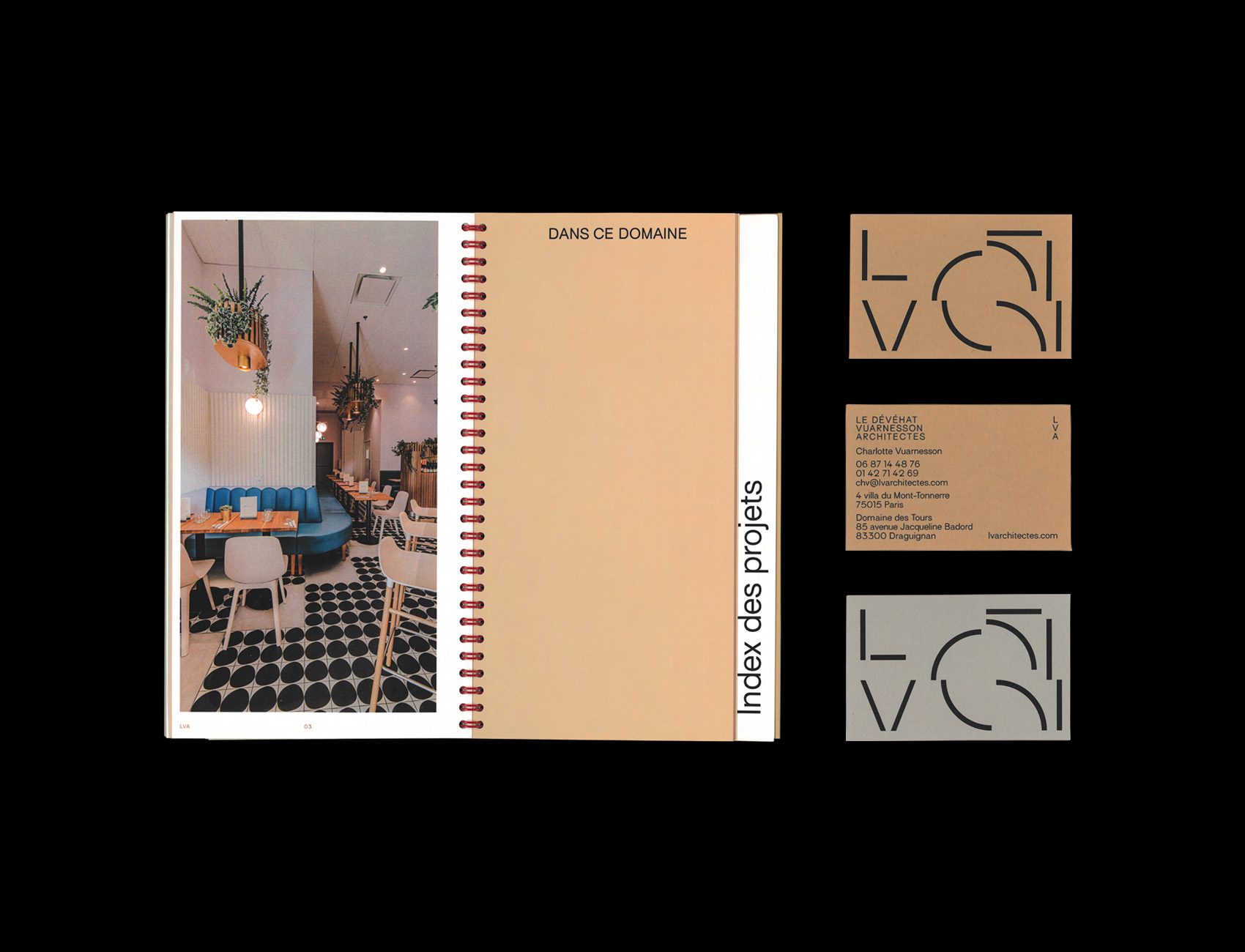

Corporate identity, stationary, agency's portfolio, website.

Air Poster, this project seems to be your playground. The game seems to be much calmer in your commissioned work. Is Air Poster your laboratory for commissioned work?

There's no doubt that at the outset, we missed the game (and also the passion for screen printing). The laboratory that Air Poster was for some ten years gave us a formal freedom that served our commissioned work and even initiated it for some of us. Although we've stopped supporting this association, we recognize the importance of giving ourselves time for pure creation... so hard to find!

Corporate identity, stationary, agency's portfolio, website.

Your studio is relatively young, but already boasts a wealth of experience. How does the dynamism of your duo enable you to cope with the pitfalls of everyday life, and what projects can we expect to see you working on in the coming year?

Relying on the other person, their perspective, their distance, their renewed patience is a daily recourse. This feedback, this passing of the baton, this in-depth support, is the basis of our energy and the driving force behind the whole.

We are continuing the collaboration we began with Veuve Clicquot two years ago, and are working with Van Cleef & Arpels on the spatial identity of several of their locations.

Over the past few years, we've been developing a number of collaborations on urban redevelopment projects, and we hope to see some of them come to fruition soon.

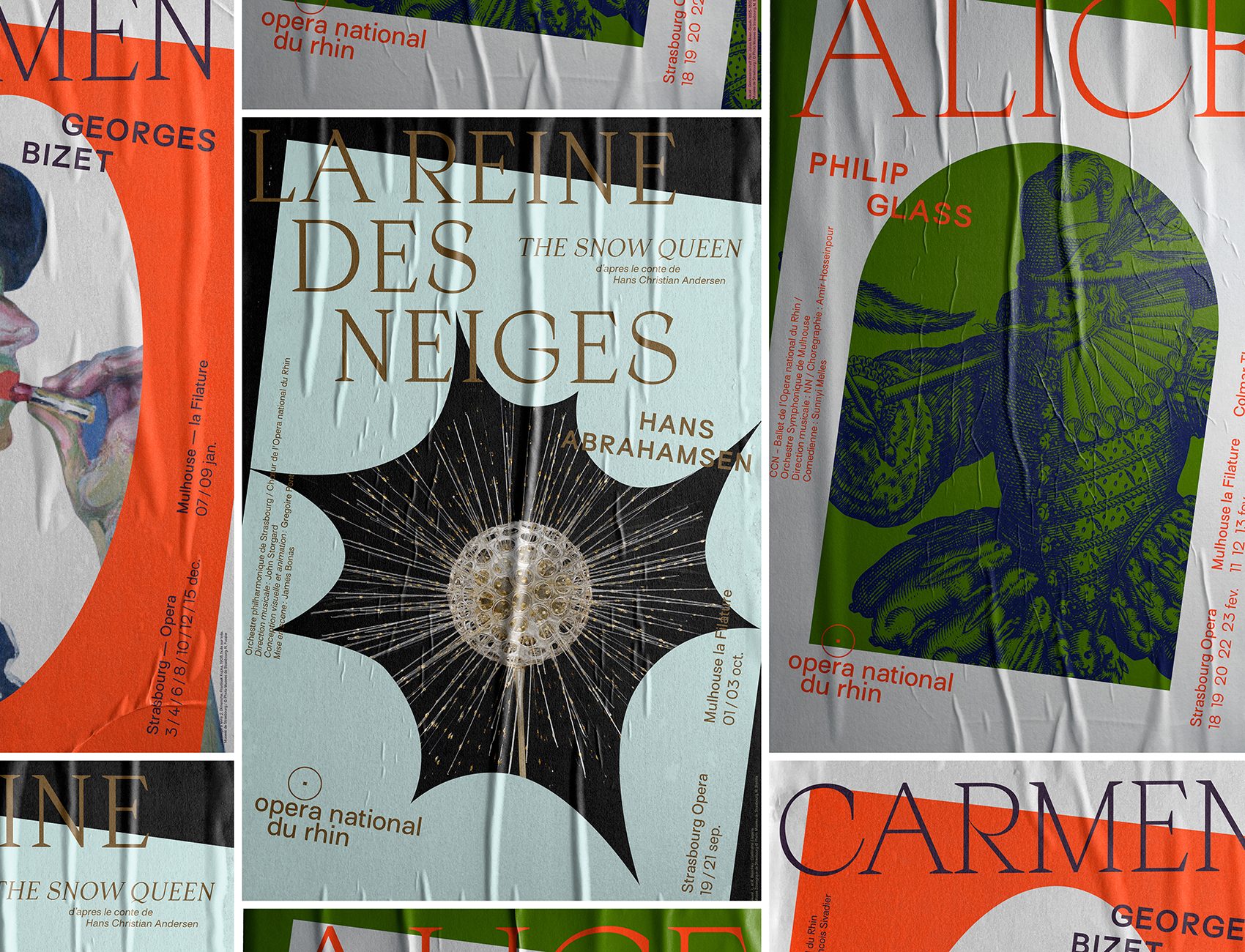

Competition for the corporate identity of the institution (unchosen project).

What is a typical day like in your studio? With a routine or recurring rituals?

We meet weekly to discuss projects and organize the week between the different designers at the studio. It's a meeting that allows us to discuss technical and organizational aspects, but also to exchange graphic ideas, things we've seen or read that can fuel the studio's creativity. We share our workspace with other designers, so lunch is often an opportunity to share ideas on other themes, to open up studio life to other perspectives and know-how.

Competition for the corporate identity of the institution (unchosen project).

What will be the place of the graphic designer for you in the decades to come, at the dawn of an Artificial Intelligence revolution?

WH : That's a huge question, and one that I think all designers are asking themselves at the moment. But I have the impression that this question isn't very well formulated, it's too abstract, too linked to our times. Provided there's enough energy, it won't be long before our work can be carried out by AIs that will become increasingly creative, powerful and precise. They will adapt at the speed of a click, they will anticipate the needs, pitfalls and challenges posed by images; they will create from gigantic databases, imagine unprecedented forms, and their responses will be hyper-adapted to the contemporary world. Today, we're creating forms that an AI could do perfectly well (probably even better!), but there's still a blind spot in this system of thought: what about the pleasure of creating these forms and sharing them? We're undoubtedly much slower, less efficient and less effective than AIs... but no one can take away the desire to create and look at shapes together. These shapes will be ours. You'll see that, in a few decades' time, AIs will be jealous of this power we have to take pleasure in doing things. If AIs really do become that intelligent, then, weary of their successes, they'll be nostalgic for failure and the body: it'll be their lost paradise.

CH: The notion of translator, designer and then intermediary is what defines my profession.

Our added value lies not so much in our ability to create the most beautiful form, THE solution to a given problem, but in our ability to interrogate a brief, to articulate it, to propose the most accurate expression with regard to the given framework and the way it was formulated by the person giving it. To feel and translate what has not been said or written.

The expression of a project is not unique; it remains the fruit of a meeting and an exchange between two individuals. Communication between these two entities takes precedence over everything else. It's the basis of the relationship of trust and respect essential to a successful collaboration.

So I see Artificial Intelligence more as an extremely powerful tool that we need to learn to work with.

booklet, posters, exhibition

What is your philosophy for the next few years: to remain at a human scale or to expand by hiring new employees?

The balance is complicated, as we see on a regular basis. Staying as involved as possible in our projects and knowing everyone inside out is a definite asset for the studio. We don't envisage working with more than a dozen collaborators.

What is the project you just finished that might have required a custom font?

We've just proposed an identity/packaging for a new perfume. One of our proposals is the use of a custom font that we've sketched out. The project is confidential, neither finished nor won... we're keeping our fingers crossed! More concretely, we've just finished designing a custom typeface for the Galerie Colbert signage. This font will be placed on furniture designed by Studio Constance Guisset, commissioned by the INHA (Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art).