By Sebastien Hayez. Published December 10, 2025

Ethan Nakache

Have you always had a fascination for letters? How did this vocation for type design come about?

As a child, I was captivated by onomatopoeia in comic strips. I loved looking at them, deciphering them, without really understanding why - there was something expressive about their shapes that fascinated me. Later, in high school, graffiti extended this attention to letters. It was then that I began to think of them as forms to be manipulated, structured and exaggerated. Graffiti led me to calligraphy, then to studies in typography and type design.

So it wasn't an immediate fascination with the alphabet as such, but with the expressive potential of the letter. Type design has established itself as a space where the rigor of design meets the freedom of gesture.

You're French and even Parisian, so why did you decide to study in Belgium at La Cambre? Does the culture of Northern Europe seem different to you from the more Latin culture of France? Do you have a different approach to design than some of your Blaze Type colleagues who studied at École Estienne?

I chose La Cambre primarily for very practical reasons: Brussels was much more affordable than Paris, which was very important to me as a student. I was also looking for a more open, less structured teaching environment than some French schools offered.

At La Cambre, we weren't really taught how to draw type in the traditional way. Above all, we were given tools - notably how Glyphs works - but without going through the historical canons of typographic design. Paradoxically, this vagueness, this absence of a model, gave me a form of freedom: I was able to develop a way of conceiving letters that didn't respond to strict standards, but remained sensitive to balance and singularity. This had its drawbacks at the beginning of my practice, in terms of proportions and vocabulary, but in the end this lack of knowledge allowed me greater creative freedom.

I would say that there is indeed a difference in culture: the Northern European approach I've encountered is perhaps more conceptual, more focused on formal research, whereas École Estienne, for example, offers teaching more rooted in tradition, history and precise execution. These two paths complement each other - but in my case, it's the margin that has enabled me to find my line.

How did you come to meet Matthieu Salvaggio and Blaze Type? How did the agreement to publish Nuances come about?

At the end of my studies at La Cambre, I was working on a free font called Sprat, which I had published under the OFL license. It was an extended family, from condensed to extended, and enjoyed some success some time later. Matthieu Salvaggio contacted me when he discovered the project: he wrote to say he'd really liked the work he'd done on Sprat, and suggested we collaborate.

We had a long chat on the phone. He suggested that we work together to design a complete, ambitious family with a wide range of styles. The idea spoke to me immediately: it was a way of extending the momentum begun with Sprat, but this time in a more professional, structured framework - with particular attention to coherence, extreme styles, and the creation of italics, something I hadn't yet tackled in my previous projects.

This is how Nuances was born: in the continuity of a personal formal research, but enriched by a real editorial collaboration and a desire to push the limits I knew in type design at the time.

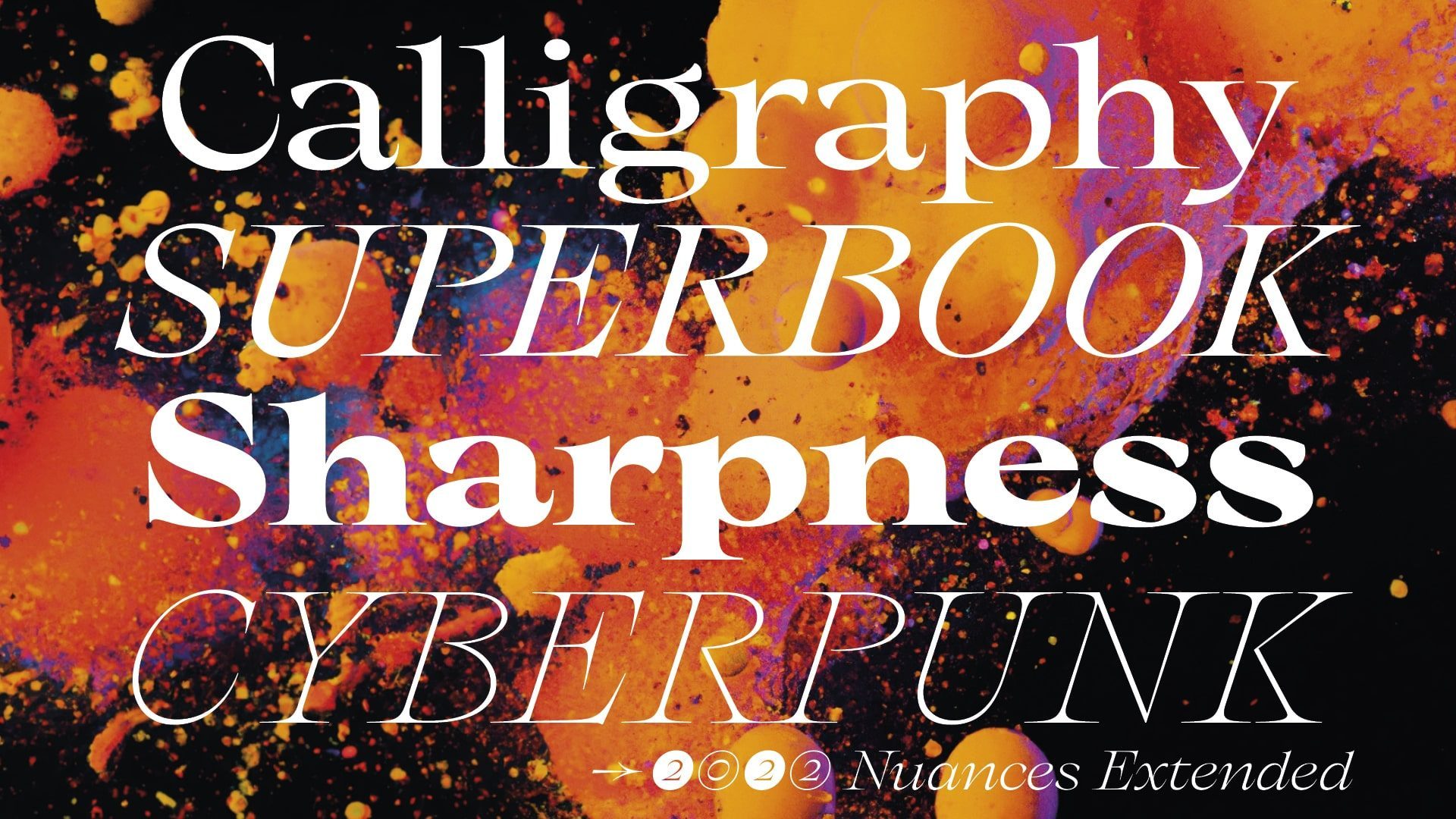

Nuances is an obvious typeface, as its name suggests: it has structure, but also many details that make it difficult to define. How did you come up with the idea for this design, and in particular the details present in the most extreme weights (the black font and the generosity of its serifs, the a & c endings almost in tapered drops, etc.)?

Nuances was born as an extension of Sprat: the initial idea was to push this extended family logic even further, by going to extremes - be it in fat weights, proportions or details. I wanted to design a typeface that was both piquant and voluptuous: with very tapered, almost sharp serifs, but also generous, round, sensual shapes. A typeface that would have character, contrast, almost a form of internal tension, while remaining consistent across the entire spectrum.

This challenge of balance was at the heart of the project: managing to maintain harmony despite the very marked differences between styles. In the most extreme weights, for example, I imagined serifs that gradually swell - this kind of "bubble" that forms allows us both to maintain a visual edge, in line with the design's DNA, while at the same time adding a density, a real typographic gray that makes reading more comfortable.

Nuances does not seek neutrality: it assumes a tone, a material, a graphic voice - while remaining rigorous in its structure.

Blaze Type makes a point of updating its typefaces, both in terms of styles and non-Latin writing systems. Is Nuances finished for good, or can we expect an extension of the family, and along what lines?

Nuances is not a finished project. I'd really like to extend the family, in particular by developing a text version, more discreet, more suitable for reading. It's a demanding, time-consuming project, and that's exactly what I'm lacking most at the moment - between personal projects and customer orders.

I've already started work on the condensed text, but there's still a long way to go before it's publishable. The desire is there, the focus is clear... All that remains is to find the right moment to bring it to fruition. So yes, Nuances should continue to evolve - but not in a hurry.

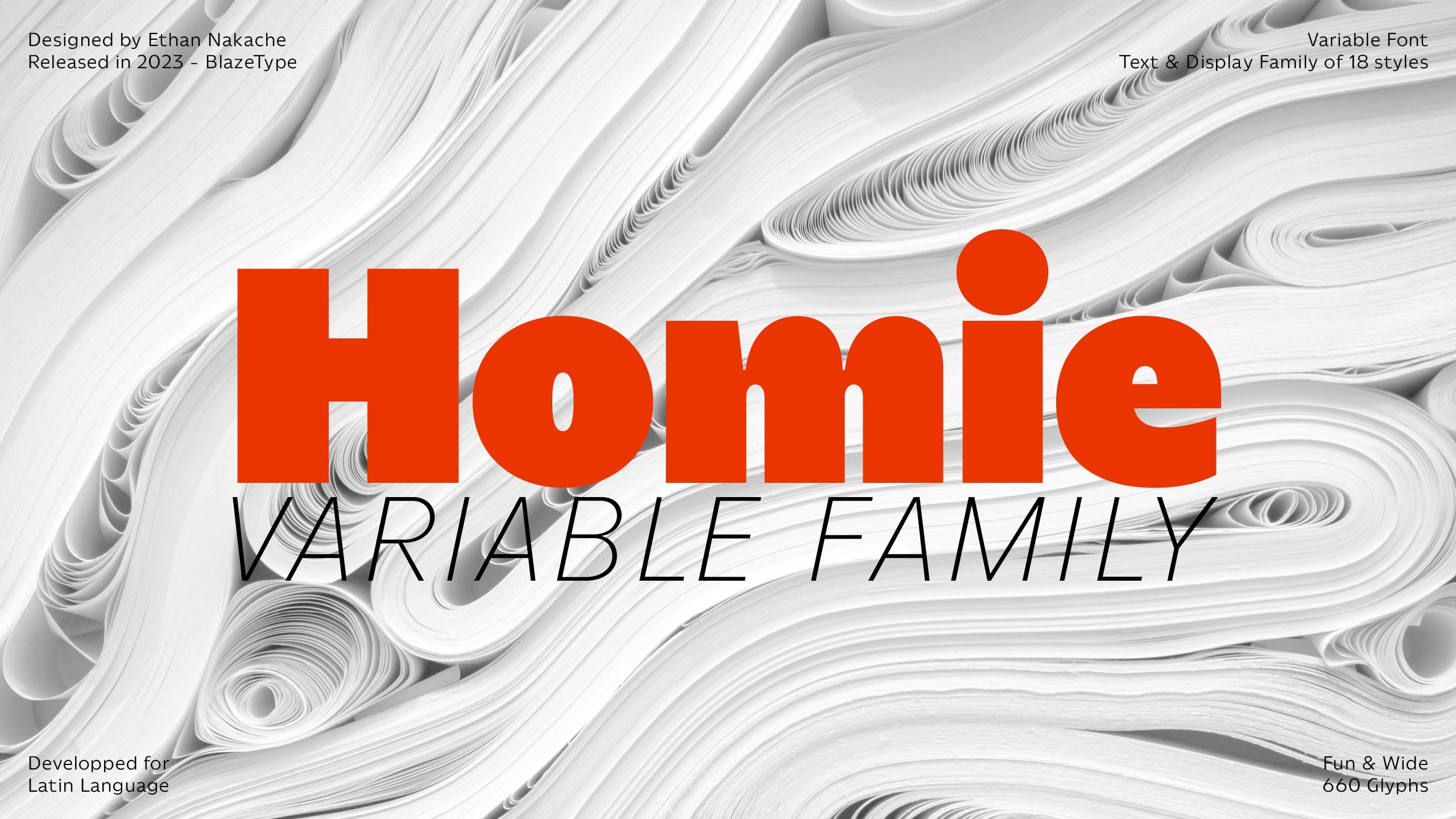

Homie is a typeface that's quite the opposite of Nuances: all surface simplicity, with a much more planted and raw look. How did you get from one to the other, and what would you say are the common threads that help us understand the "character" of its creator?

With Homie, I wanted to explore a nicer, more direct form of drawing, and above all to tackle a Sans - an exercise I'd rarely tackled in my practice at the time.

Homie starts from a humanist model, but pushes certain strokes towards more geometric, more constructed forms. As the weight increases, the letter becomes more established, taking its place, almost physically. This change of inner contrast is a central element of his personality: light styles are made for reading, heavy styles for impact.

If I were to find a link between Nuances and Homie, it would probably be in this attention to tension - this desire to build highly structured systems, but where forms remain free, alive. I think what I try to preserve in my caracters, whatever the style, is a certain balance between rationality and aesthetics.

Homie doesn't have true italics, as some typical glyphs (a, g) do, but you have to activate them through stylistic set. Why did you choose slanted over true italics by default?

As far as I'm concerned, Homie is a true italic, and for certain emblematic glyphs such as the a, g or l, I've actually chosen to retain the forms of the roman in the default italic.

This was a purely aesthetic choice. These letters - particularly the a and g - are very representative of Homie's visual DNA, and I felt they continued to work well in the rhythm of italics. I didn't want to lose this strong identity.

For users who prefer a more classic italic, I've included stylistic alternates with more traditional cursive forms that can be easily activated. It's a way of offering a double reading: respecting the character of the original design, while leaving room for interpretation according to the user's needs.

Is there a particular glyph you enjoy drawing when creating typography?

Yes, there are a few that come up almost systematically. I immediately think of the S, the c, the g and the ampersand. These are letters that, to my mind, crystallize a lot of a typeface's DNA.

They concentrate tensions, rhythms and contrasts - and also offer a real margin of freedom in their design. You can have a bit of fun with them, looking for variations or subtleties of form, without it interfering with the reading.

It's often on these glyphs that I feel if a font "takes", if it's coherent, if it has something to say. It's almost instinctive: if these letters work, the rest follows, (obviously after you've found the structure between H and O!).

Do you have any other upcoming projects with Blaze Type, or what type of family would you like to develop in the future?

For the moment, I don't have any new concrete projects in the pipeline with Blaze Type, apart from the desire to produce the text version of Nuances, as soon as I have the time. It's an extension that's close to my heart, and one that I'd really like to finalize under the right conditions.

Of course, I remain open to other collaborations with Blaze Type in the future. Working with Mathieu has always been a pleasure, and he's become a friend over the years, so the desire to team up again is there.

After that, you never know what the future holds... Right now, I've got a few projects on the go that need to be completed.

Which typefaces in the Blaze Type catalog do you secretly admire, and why?

There are several I admire in the catalog, each for different reasons.

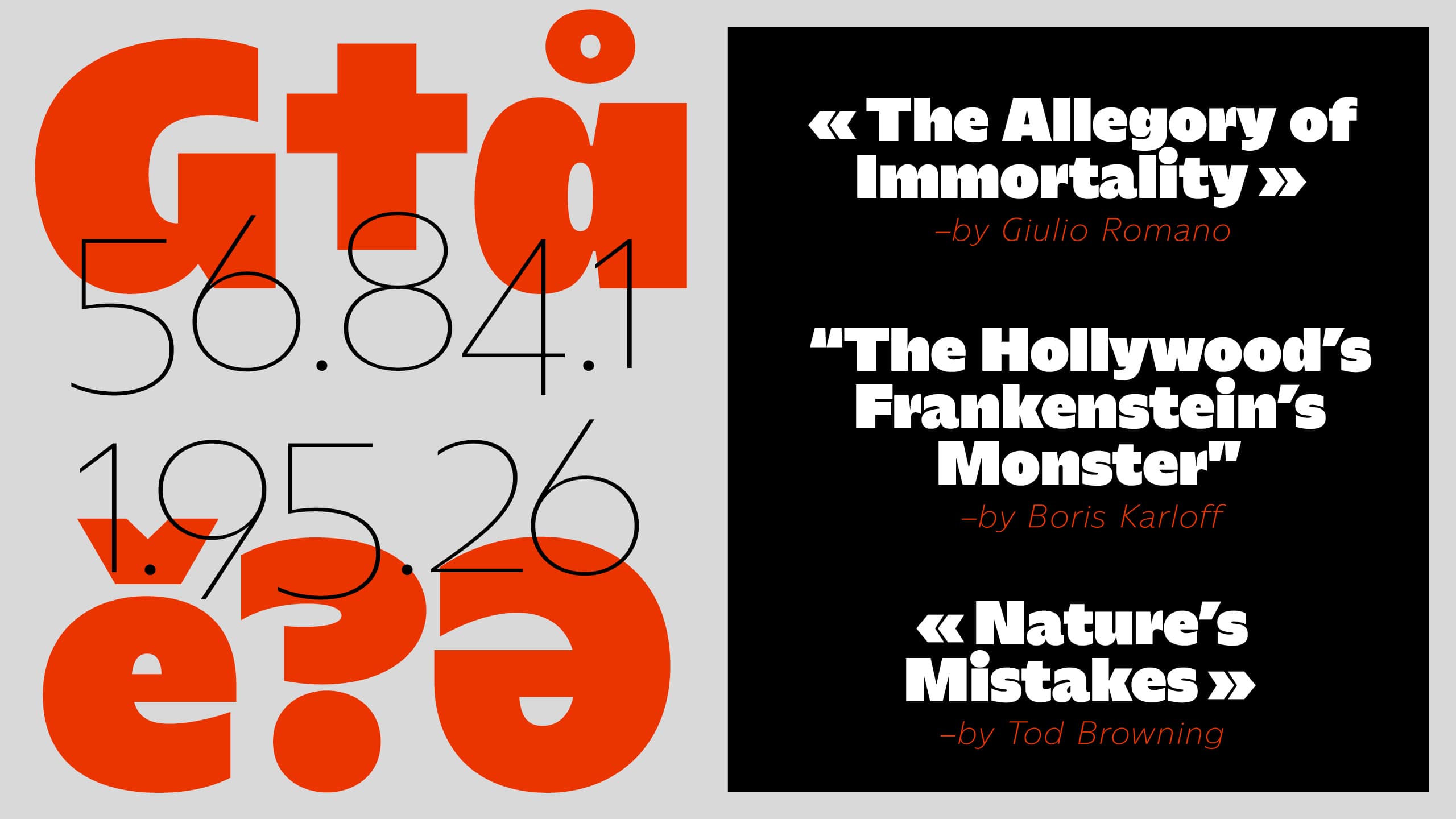

On the side of rigor and ambition, I'd say Slussen. It's a typeface I respect enormously for the scope of the work, the coherence of the system and the quality of its execution. It's a truly global design project.

On a more aesthetic level, I have a real fondness for Sagittaire, which explores very round, very sensual shapes, while maintaining a very strong contrast. There's something very strong in this tension between softness and radicalism.

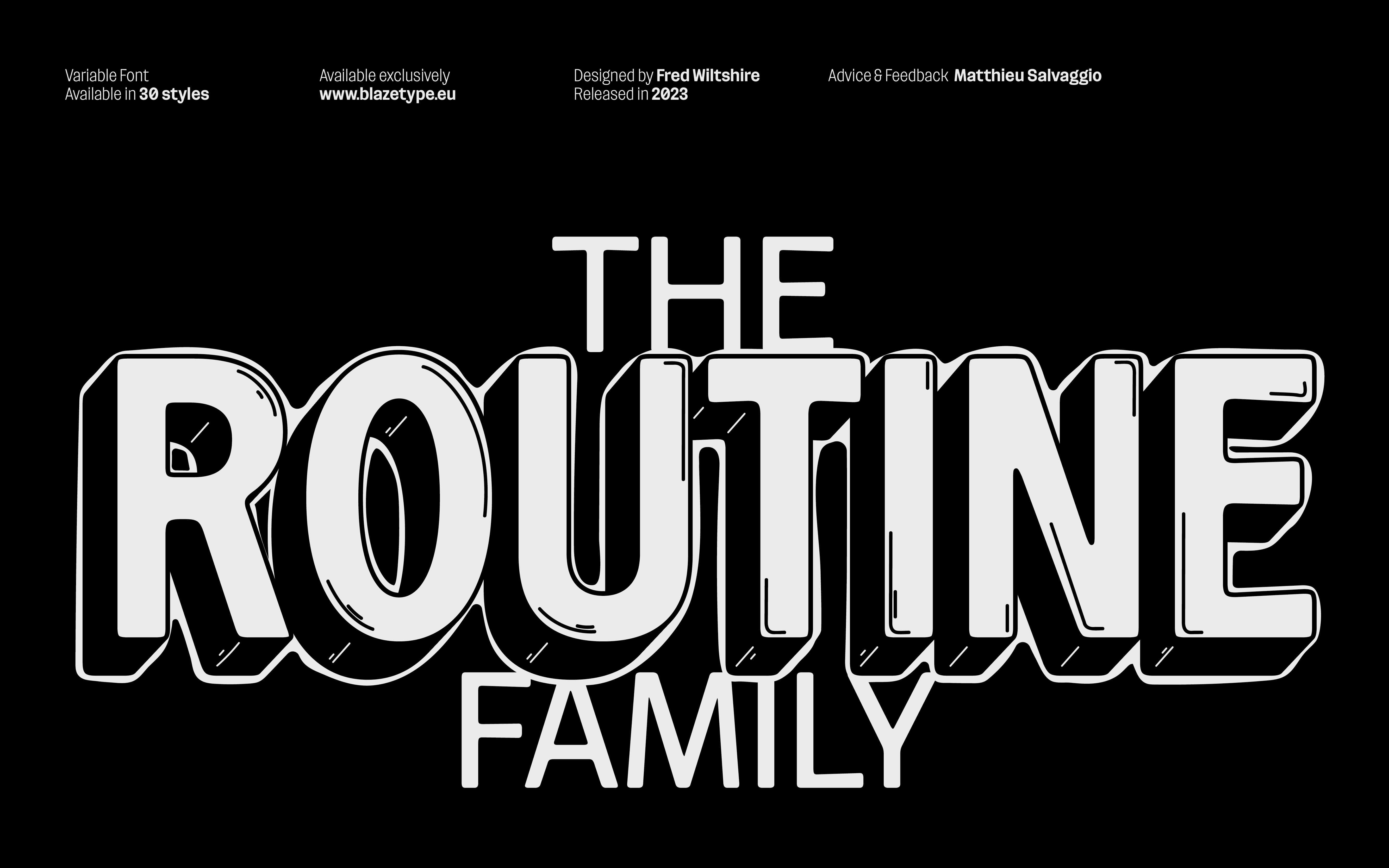

And on a more playful note, I think Fred's Routine works really well. He manages to inject real graphic pleasure into a more classic structure, with great accuracy and freshness. It's a difficult balance to strike, and I think he does it very well.